This paper was prompted by several factors: (1) an earlier invited chapter,included in a book entitled Civil Society and Social Responsibility in Higher Education, created in partnership with the International Higher Education Teaching and Learning Association; (2) increasing global awareness and adoption of the One Health (and Wellbeing) concept/approach across political arenas and disciplines; and (3) the urgency for academia - as it has historically done - to take a leadership role in responding to the unprecedented and complex challenges the world now faces with climate change and upholding democracy at the top of global agendas. Recent elections in several European countries represent a welcome shift from authoritarianism and populism - the erosion of liberal values - to centrist politics, a trend that may be cause for optimism around the world. Education, formal / non-formal, research and community engagement are key, as UNESCO advocates, in bringing “shared values to life” and cultivating “an active care for the world and for those with whom we share it.” Transforming the way we “think and act” necessitates a more holistic understanding of planet sustainability as well as re-thinking what and how we learn and, in particular, re-directing current conceptualisations of curricula, research and policy development toward a new academic “knowledge ecology (symbiotic relationship) between all living things and the environment) through the development of an “interconnected ecological knowledge system.” Time is not on our side. The UN International Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) in its latest report has warned that unless we limit global warming to 1.5C. and cut carbon emissions by 43% by 2030 the world is on course for catastrophic warming of 3.2 C by the end of this century. Biodiversity loss, emerging infectious diseases, such as Covid-19, and geopolitical tensions are also at the forefront of global crises in this decade, which must surely lead us to question our fundamental relationship to the planet and to each other. Because of subject-matter scope, the paper is being published by PEAH in three parts over few weeks span: Part 1: The One Health & Wellbeing Concept Part 2: Development of a Global ‘All Life’ narrative Part 3: The international One Health for One Planet Education Initiative (1 HOPE) and the ‘ecological university’

![]()

By George Lueddeke, PhD

Consultant in Higher, Medical, and One Health Education

Global Lead – International One Health for One Planet Education initiative (1 HOPE)

Reflections on Transforming Higher Education for the 21st Century

Bringing ‘Shared Values to Life’

PART 1: The One Health and Wellbeing Concept

Article purpose

This paper examines how higher education can be encouraged to “think beyond ‘narrow academic pursuits” and become more “productive, disruptive forces for positive change and progress capable of understanding and solving complicated real-world problems.”

To these ends, the article considers four main themes:

- existential risks facing our planet and civilisation;

- a new worldview and narrative for global sustainability;

- an international education initiative to help sustain life on the planet;

- building interdisciplinary knowledge systems with “a concern for the whole Earth”.

Taken together, they lead to considerations for university transformation and global sustainability.

Planetary risks in the early decades of the third millennium

Planet Earth is now in its sixth mass extinction phase with global wildlife decline – ‘the living forms that constitute the fabric of the ecosystems’– about 68 percent loss since 1970. The last species’ extinction on this scale was 65 million years ago when an asteroid wiped out the dinosaurs.

As mentioned in Planet Earth: Averting a Point of No Return, we have become that “asteroid.” The urgency to reconsider civilisation priorities, integrate new values and adopt a more sustainable way of life could not be greater. To a large extent, beginning with the industrial era in the mid-eighteenth century, human progress has been accomplished at a high cost as Professor Samuel Myers in his lecture for the Academy of Medical Sciences at Harvard University reminded us a few years ago:

“… the scale of human impacts on our planet’s natural systems is hard to overstate: to feed ourselves, we annually appropriate about 40% of the ice-free, desert free terrestrial surface for pastures and croplands; we use about half of the planet’s accessible water, largely to irrigate our crops, and we exploit 90% of global fisheries at, or beyond, their maximum sustainable limits. In the process, we have cut down 7–11 million km² of the world’s forests and dammed more than 60% of its rivers. The quality of air, water, and land is diminishing in many parts of the world because of increasing global pollution. These and other processes are driving species to extinction at roughly 1000 times baseline rates while reducing population sizes of mammals, fishes, birds, reptiles, and amphibians by half in the past 45 years.”

Towards a new worldview

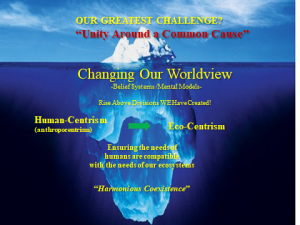

Our worldview remains the main obstacle or culprit in our struggle for planet survival. As shown in Figure 1, the world can be viewed through two main lenses: anthropocentric (human-centrism) or ecocentric (all life). In their comprehensive qualitative and quantitative grounded theory study How Ecocentrism and Anthropocentrism Influence Human-Environment Relationships in a Kenyan Biodiversity Hotspot, the authors note that

“While an anthropocentric mindset predicts a moral obligation only towards other human beings, ecocentrism includes all living beings. Whether a person prescribes to anthropocentrism or ecocentrism influences the perception of nature and its protection and, therefore, has an effect on the nature-related attitude.”

The authors of Why ecocentrism is the key pathway to sustainability “see ecocentrism as the umbrella that includes biocentrism and zoocentrism because all three of these worldviews value the non-human with ecocentrism having the widest vision.” In support, they cite Stan Rowe’s scientific rationale that “backs the value shift”: “All organisms are evolved from Earth, sustained by Earth. Thus Earth, not organism, is the metaphor for Life.”

Figure 1: Human-Centrism and Eco-Centrism

(Source: PEAH- COP26: Tackling the Root Causes of Climate Change, 2021)

Integrative health concepts underpinning sustainability

According to a Johns Hopkins University study distinguishing among three main interdisciplinary health concepts involving global experts, the researcher identified three main camps, including:

(1) those that deal with “improving human health from the population perspective, transcending national borders, some including both preventive and individual-level clinical aspects” (e.g., public health, global health).

(2) those that are “largely concerned with the sustainability of our civilisation and resource consumption on the planet and human health” (e.g., planetary health, ecological health); and

(3) those that “encompass human, animal, plant, and environmental health and well-being” (e.g., One Health, One World-One Health).

The One Health concept

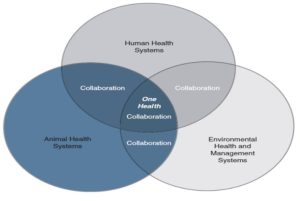

As shown in Figure 2, and underscored by the authors of ‘A Blueprint to Evaluate One Health,’ the One Health concept is integral to the ecocentric ethic (a moral purpose?), that is, shifting from reactive sectoralised interventions (‘it’s all about us’) to multi-sector preventive actions at social, ecological, economic and biological levels of society” (‘it’s about all species’).

Figure 2: The One Health Triad

(Source: World Bank - ONE HEALTH Operational Framework for strengthening human, animal and environmental public health systems at their interface, 2018)

This holistic perspective is reflected in the definition of One Health by the One Health High Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP) established on 21 May, 2021, co-chaired by Professor Wanda Markotter and Professor Thomas Mettenleiter. Responding to “global health threats” and promoting “sustainable development” with a view to developing “a common language and understanding around One Health”, members agreed that:

One Health is an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals, and ecosystems.

It recognizes the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment (including ecosystems) are closely linked and inter-dependent.

The approach mobilizes multiple sectors, disciplines and communities at varying levels of society to work together to foster well-being and tackle threats to health and ecosystems, while addressing the collective need for clean water, energy and air, safe and nutritious food, taking action on climate change, and contributing to sustainable development.

Considered historically, the origins of One Health can be traced to ancient Greece and “father of medicine,” also considered the first epidemiologist, Hippocrates (c. 400 BCE), who urged physicians to consider the environment in which patients lived. While sanitation in ancient Rome is “legendary,” it likely made things worse largely because of parasitic infections, and it took another 1800 years or so before basic understanding of the causes of diseases was possible.

In separate articles published in 2014, Professor John McKenzie et al. in Australia and Professor Paul Gibbs in the United States reached similar conclusions regarding One Health milestones. Both recognised major contributions in the 19th and 20th centuries of individuals such as Dr. Rudolph Virchow, “the father of comparative medicine,” Sir William Osler, Sir John McFadyean, Dr. James Steele and Dr. Calvin Schwabe; to name but a few leading lights.

The increase and severity of viral pandemics sweeping across the world in the 1990s and early decades of the 21st century spawned the proliferation of One Health organisations and networks. These included – in 2004: the Wildlife Conservation Society; in 2008: the American Veterinary Association, the One Health Initiative, the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention; in 2009: Afrique One – ASPIRE , the One Health Commission; in 2010: the Tripartite FAO, OIE, WHO, UNICEF, UNISIC, the World Bank, the EcoHealth Alliance, the European Union. One Health reports and conferences (e.g., Australia, Canada, China, South Africa, USA) alerted the world about the on-going microbial threats, emerging diseases, influenza, and pandemics.

While these developments were welcomed by the One Health community and policymakers, it became clear that there was a need for strengthening collaboration among multi-disciplinary partnerships and developing the expertise to operationalise the One Health approach. Both McKenzie and Gibbs called for leadership development, multi-level education and training courses, cost benefit analyses, and increasing interdisciplinary engagement beyond veterinary and human medicine.

Professor Gibbs’ query was particularly timely and relevant in 2014: Is One Health simply “a short-lived response” to “emerging diseases” or “a paradigm shift” leading “to a wide and deep-rooted commitment to interdisciplinary action for the protection and needs of society in the 21st century.”?

The first report, entitled the World at Risk in 2019, of the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board (GPMB), chaired by Dr. Gro Harlem Brundtland, former Prime Minister of Norway and Director-General of the World Health Organization, reflected an on-going concern for the slow global response to pandemics and impending global crises highlighting “a cycle of panic and neglect.”

Early 2020 Covid-19 confirmed the world’s unpreparedness for a major global pandemic with unprecedented deaths, cases and socio-economic consequences leading to a frantic search for vaccines and unparalleled lifestyle changes – shining a light on global inequities and the need to place responsibility for the root causes of climate change, biodiversity loss and emerging infectious diseases on humankind.

Accountability for global threats was confirmed for the first time with statements referencing One Health by member countries of the Joint G20 Finance and Health Minister Meeting Communiqué in 2021 and the G7 Leaders’ Statement 2022 – perhaps recognising that no single nation has the capacity to address global existential risks we face and heeding esteemed naturalist and broadcaster Sir David Attenborough’s wake-up call: