This paper was prompted by several factors: (1) an earlier invited chapter,included in a book entitled Civil Society and Social Responsibility in Higher Education, created in partnership with the International Higher Education Teaching and Learning Association; (2) increasing global awareness and adoption of the One Health (and Wellbeing) concept/approach across political arenas and disciplines; and (3) the urgency for academia - as it has historically done - to take a leadership role in responding to the unprecedented and complex challenges the world now faces with climate change and upholding democracy at the top of global agendas. Recent elections in several European countries represent a welcome shift from authoritarianism and populism - the erosion of liberal values - to centrist politics, a trend that may be cause for optimism around the world.

Education, formal / non-formal, research and community engagement are key, as UNESCO advocates, in bringing “shared values to life” and cultivating “an active care for the world and for those with whom we share it.” Transforming the way we “think and act” necessitates a more holistic understanding of planet sustainability as well as re-thinking what and how we learn and, in particular, re-directing current conceptualisations of curricula, research and policy development toward a new academic “knowledge ecology (symbiotic relationship) between all living things and the environment) through the development of an “interconnected ecological knowledge system.”

Time is not on our side. The UN International Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) in its latest report has warned that unless we limit global warming to 1.5C. and cut carbon emissions by 43% by 2030 the world is on course for catastrophic warming of 3.2 C by the end of this century. Biodiversity loss, emerging infectious diseases, such as Covid-19, and geopolitical tensions are also at the forefront of global crises in this decade, which must surely lead us to question our fundamental relationship to the planet and to each other.

Because of subject-matter scope, the paper is being published by PEAH in three parts over few weeks span:

Part 1: The One Health & Wellbeing Concept

Part 2: Development of a Global ‘All Life’ narrative

Part 3: The international One Health for One Planet Education Initiative (1 HOPE) and the ‘ecological university’

![]()

By George Lueddeke, PhD

Consultant in Higher, Medical, and One Health Education

Global Lead – International One Health for One Planet Education initiative (1 HOPE)

Reflections on Transforming Higher Education for the 21st Century

BRINGING ‘SHARED VALUES TO LIFE’

PART 2: Development of a Global ‘All Life’ Narrative

(Part 1: The One Health and Wellbeing Concept)

On human thought, Beliefs, and behaviour

Throughout the millennia education has played a critical role in shaping human interactions, including to the present when after 4.5 billion years of evolution and revolutions – cognitive, agricultural, scientific, information– humanity is now at a precipice.

In A vision for human well-being: transition to social sustainability, the authors argued that “[M]aintaining a healthy environment and transitioning toward sustainability” is difficult as “communities and societies are inherently conservative, and do not change unless something pushes them… despite the fact that many see disaster looming.”

Two of their key premises are that sustainability requires “human societies that function well” and that “social, economic and political breakdown only perpetuates environmental abuses.” The main obstacles to sustainable development, they asserted, can be traced to global unwillingness or capacity “to provide the resources necessary of the communities most in need” by ensuring “a more equitable global distribution of resources and empowerment” and “a global focus on growth in well-being instead of consumption.”

Taking a largely humancentric stance, the authors advanced that in order to achieve these aims we need a “systematic effort to monitor progress towards well-being (physical, social, emotional) and understand its drivers, “while recognising that communities currently in poverty will need additional consumption in order to do well.”

However, simply acknowledging that deprivation, hunger, suffering and inequities exist is not enough. We have the data, but, as David Wiebers, Emeritus Professor of Neurology at Mayo Clinic posits, too often we lack the “principal motivation to reach beyond ourselves and beyond what we may have thought possible, ” including extending “compassion and care” to “beings other than humans, who also have a consciousness and a set of yearnings that demand uncompromising respect.” For Professor Wiebers “Scientific achievement is indeed a wonderful thing-in direct proportion to how much it either reflects or reinforces compassion for all life.”

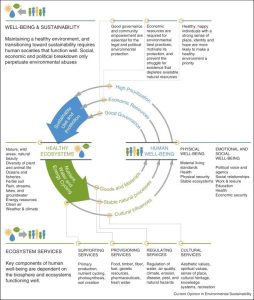

As Figure 3 illustrates, both human and ecosystem measures (non-human animals, plants, environment) are critical as these interventions determine the health and wellbeing of humankind in a reciprocal relationship.

Figure 3: Links between human well-being and the environment

(Source: Science Direct: A vision for human well-being: Transition to social sustainability [2012])

Building blocks for global sustainability

Today’s unprecedented perils demand major transformations to move societies in the direction of social and environmental sustainability. According to the authors, previously cited, of ‘Why ecocentrism is the key pathway to sustainability,’ anthropocentrism, which, as mentioned, “values other lifeforms and ecosystems insofar as they are valuable for human well-being, preferences and interests,” remains the main “ideology in most societies around the world – permeating academia and domestic and international governance.”

In contrast, the authors contend “that a fully sustainable future is highly unlikely without an ecocentric value shift that recognises the intrinsic value of nature and a corresponding Earth jurisprudence.” Underpinned by ecocentric values and principles, learning that “cultivates an active care for the world and with those we whom we share it” remains our best option for ensuring the sustainability of the planet and all life. To these ends, several key constructs and developments are particularly timely and pivotal in shaping global education and research environments: the One Health (and Wellbeing) concept applied to all species and the planet, the Earth Charter and the UN-2030 Sustainable Development Goals:

The One Health and Wellbeing Concept

The concept/approach, discussed previously, underpins the belief that “the health of people, other animals and the ecosystems of which we are a part are inextricably woven together,” and emphasising “ respect and care to all life, and indeed to terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems themselves.”

The Earth Charter

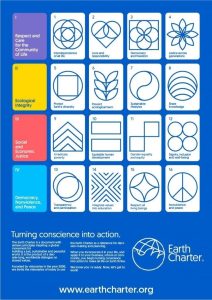

Launched in 2000, the Earth Charter, (EC) was “[C]rafted by visionaries over twenty years ago” and, as summarised in Figure 4, “is a document with sixteen principles, organized under four pillars that seek to turn conscience into action” and “inspire in all people a new sense of global interdependence and shared responsibility for the well-being of the whole human family, the greater community of life, and future generations. It is a vision of hope and call to action.

The EC Education Center, located on the campus of the UN Mandated University for Peace in San José, Costa Rica, “offers a variety ofonline and on-site education programmes that highlight the importance of incorporating sustainability values and principles into decision-making and education. Its “work is implemented under the UNESCO Chair on Education for Sustainable Development with the Earth Charter, which generates educational programmes and research activities at the intersection of sustainability, ethics and education.”

Figure 4: The Earth Charter

Pillars and Principles -‘Turning Conscience into Action’

(Source: Earth Charter Organisation: Celebrating 20 years of the Earth Charter with a new face! [2020])

The UN Global Goals

Millennium Development Goals (2000-2015)

Coincidentally, the year 2000 also saw agreement by world leaders at a UN summit of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) setting targets for poverty reduction, primary education, equality, child mortality, maternal health, HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases, environmental sustainability and global partnerships.

While the final report acknowledged that progress was “made across the board, from combatting poverty, to improving education and health, and reducing hunger, “ much more needed to be done. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon in the report Foreword highlighted that “we know what to do” and called for “unswerving political will, and collective, long-term effort“: tackling root causes and do more to integrate the economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainable development.”

The Sustainable Development Goals (2016-2030)

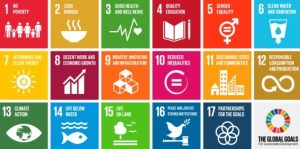

Superseding the MDGs, on 25 September 2015, 193 Member States of the United Nations General Assembly ratified the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [2016])

(Source: United Nations, [2016])

The UN Transformative Vision underpinning the seventeen SDGs focuses on both human and environmental needs prioritising the interconnections between the two. In the past few years, the root causes of global threats have become much clearer as are attempts to address these (e.g., surveillance data, green economy, prevention [vaccines]). However, global adoption of the SDGs and in particular its main aim to “create a more just, sustainable and peaceful world” remains a fundamental global challenge as current events and on-going risks are demonstrating. Truth, trust, compassion, and collaboration are key to planet sustainability but continue to be eroded by authoritarian agendas that place self-interests (e.g., geographical expansionism) despite the fact that climate change and conflicts threaten the future of all species including homo sapiens.

In this regard Professor Jared Diamond’s seminal book, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive, based on, among others, “ancient Maya, Anasazi and Easter Island” societies,” is even more critical today than in 2005 when it was first published. Main reasons for societal demise, the author concluded, were lack of “long-term planning and willingness to reconsider core values.” While the present world situation seems irreconcilable, perhaps placing our faith and trust in the new generation – Generation Z (born from 1997 onward) – is the way forward. As Mary Meehan, a cultural scientist said in a Forbes article several years ago: “They represent boundary-blurring countries and the reality of our shifting global culture. Already they display a great interest in and tolerance of ‘others.’ ”

A recent US cultural intelligence report entitled Gen Z Complexities: You’ve Only Heard Half the Story highlights that in terms of politics, Gen Z “are perceived to neatly fit under a liberal umbrella, focused on issues like social justice, climate activism, gun safety and voting rights.” In addition, climate change and inaction are major concerns” prompting many to commit “their lives to finding a solution.” Gaining “economic, social, and political power, the changes they’ll look to make will be structural, but not superficial” – which could not only encourage” humans to reconnect with their planet,” as Professor Johan Rockström at the Stockholm Resilience Center advocates, but also take on board the urgency to re-orient thinking from ‘it’s all about us’ (human-centrism) to ‘it’s about all species and planet sustainability (ecocentrism)”.

Impact of Covid-19 on SDG progress

The SDG Report 2020, prepared by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) in collaboration with more than 50 international agencies, noted that progress on meeting SDG targets was already slow with many of the goals not reaching their targets by 2019. While the latter report was disappointing, the SDG Report 2021 was devastating, as most of the developments over the past few years, were “halted or reversed,” also underscored in a The Lancet Public Health editorial . The pandemic had “exposed and intensified inequalities within and among countries” as well as crises relating to climate, biodiversity loss and pollution, including increasing poverty, hunger, health, education, sanitation, greenhouse gas emissions, infectious diseases, to name a few areas – all threatening “peace and safety from violence” requiring “a major realignment of most countries’ national priorities toward long-term, cooperative, and drastically accelerated action.”

The university sector: Valuing the SDGs – Impact Rankings 2021

In July 2019, the President of the 8th Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) Youth Forum, where voluntary national reports against the SDGs were considered, voiced similar concerns calling “upon young people to continue to raise their voice, advocate for the SDGs, and hold their Governments accountable for the commitments made in the 2030 agenda.”

In this respect The Times Higher Education SDG Impact 2021 global university performance tables may be telling. The impact rankings are “the only global performance tables that assess universities against the UN SDGs” providing “comprehensive and balanced comparison across four broad areas: research, stewardship, outreach and teaching.” The 2021 impact rankings include submissions from 1,118 universities and 94 countries/regions. The UK’s University of Manchester leads other universities for the first time along with three Australian universities – the University of Sydney, RMIT University and La Trobe University in the top four. Interestingly, ‘Russia is the most-represented nation in the table with 75 institutions, followed by Japan with 73.’

Perhaps unsurprisingly, in terms of research priorities all top universities still focus on human health and well-being (human-centrism – SDG # 1,4,5,10,16; SDG #8, Decent Work and Economic Growth, and SDG #9, Industry Innovation and Infrastructure) and not with ensuring the sustainability of all life – plants, nonhuman animals and the environment (eco-centrism-) on which all life on this planet depends (SDG# 13,14,15 and climate emergency). SDG #16, Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions is mentioned by only 5. Few universities, it seems, have considered how many of the solutions we seek are found in the natural world.

Toward a new narrative for global sustainability (research and education!)

In his groundbreaking paper, ‘Implications of Transformative Changes for Research on Emerging Zoonoses,’ Professor Thijs Kuiken, argues for “a new narrative that promotes a sustainable way of living” and, as summarised in the Table, “would be an integral part of nature and balance our needs with those of other living species”. While his article focuses on zoonosis – infectious diseases of animal origin, his proposal has wider implications for education, research and public policy and transformative change toward sustainability implemented by “leaders of universities, institutes, societies, and funding bodies” across societal sectors and disciplines”.

Table: Possible Effects of a New Narrative on Choice of Problems, Methods and Solutions of Research on Emerging Zoonoses

(Source: EcoHealth: ‘Implications of Transformative Changes for Research on Emerging Zoonoses, 2021)

| Research section | Current narrative | New narrative |

| Research problem formulation | Focus on human health | Equal attention to health of ecosystems, animals, and humans |

| Emphasis of financial cost to society | Equal attention to ecological, social, and financial costs to society | |

| Restricted scope e.g., interaction between pathogen and human cost only | Broad scope: interrelated ness of all organic and inorganic elements in the system included | |

| Choice of scientific methods | Emphasis on financial cost | Equal emphasis on environmental impact |

| Development of solutions for addressing zoonotic disease issues | Emphasis on current event | Attention to all events of this nature |

| Short term | Also, long-term | |

| Solution for proximate causes well accepted | Solution for proximate causes accepted only if action undertaken to deal with ultimate causes | |

| Acceptability determined by possibility to continue financial profit of human activity involved | Acceptability determined by improvement to health and well-being of humans and animals, and to health integrity of ecosystems |

Reconciling global funding inequities and addressing new existential challenges

Adoption of a new ecocentric narrative could also raise awareness, highlighted in an informative article last year by Dr Bruce Kaplan, co-founder of the One Health Initiative and Richard Seifman, UN Association of the National (USA) Capital Area. A follow-up commentary underscored the pressing need to strengthen funding of world organisations, including WHO which receives approximately US $6 billion annually; the FAO, c. $2.6 billion and the OIE (the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), only c. $32 million!

As investments in humanity’s future, these figures pale in comparison to the global human and financial costs of Covid-19 to date: 6.25 million deaths as well as 517 million cases; and economic costs: US $ 12.5 trillion and beyond , set against a world annual economy (Gross Domestic Product [GDP] – all goods and services) estimated around $ 95 trillion in 2021 and Global military spending which for the first time stands at US $ 2 trillion – with mainly the USA, China, India, UK, and Russia spending 65 % of the total.

These amounts are staggering and should make government and corporate policymakers re-think the rationales of these escalating expenditures, human values that underpin them and where they may eventually lead if not reconsidered on moral or injustice grounds alone and how to mitigate these in future.

Worldwide, about US $4.7 trillion are allocated to education annually but “only 0.5% is spent in low income countries, while 65% is spent in high income countries, even though the two groups have a roughly equal number of school-age children.” Public spending on higher education is about US $1 trillion per year with a major “shift of higher education’s centre of gravity from the Global North to the Global South,” according to a “definitive world report” launched the by Toronto-based Higher Education Strategy Associates (HESA).

The number of higher education institutions in the Global South “nearly doubled from a little over 40,000 to nearly 70,000, to reach a global institutional total of 90,000” (versus c. 20,000 in the Global North.) However, “the number of dollars per student is going up in the North, but going down in the South,” while funding in the Global North is allocated to “quality, equity and research,” whereas “[I]n the Global South, the money mostly goes to increased capacity and access.”

Concluding comment

In the introduction to the SDG Report 2021, Liu Zhenmin, UN Under-Secretary-General for Economic and Social Affairs, calls for “a unified vision of coherent, coordinated and comprehensive responses from the multilateral system.” In light of the unprecedented risks we face (climate change, democracy, political tensions), global responses aligned with the SDGs necessitate, as the UN USG asserts, “action and participation from all sectors of society, such as “ Governments at all levels, the private sector, academia, civil society and individuals – youth and women, in particular.”

————————————-

Parts 1 and 2 of the present article have argued for the wider adoption of the ecocentric One Health and Wellbeing concept to underpin the Earth Charter values and principles and together informing the UN Transformative Vision and action, including cultivating, as UNESCO advocates, “an active care for the world and for those with whom we share it.” Part 3 to follow considers societal options -education and policy directions - for doing so.