This paper was prompted by several factors: (1) an earlier invited chapter,included in a book entitled Civil Society and Social Responsibility in Higher Education, created in partnership with the International Higher Education Teaching and Learning Association; (2) increasing global awareness and adoption of the One Health (and Wellbeing) concept/approach across political arenas and disciplines; and (3) the urgency for academia - as it has historically done - to take a leadership role in responding to the unprecedented and complex challenges the world now faces with climate change and upholding democracy at the top of global agendas. Recent elections in several European countries represent a welcome shift from authoritarianism and populism - the erosion of liberal values - to centrist politics, a trend that may be cause for optimism around the world.

Education, formal / non-formal, research and community engagement are key, as UNESCO advocates, in bringing “shared values to life” and cultivating “an active care for the world and for those with whom we share it.” Transforming the way we “think and act” necessitates a more holistic understanding of planet sustainability as well as re-thinking what and how we learn and, in particular, re-directing current conceptualisations of curricula, research and policy development toward a new academic “knowledge ecology (symbiotic relationship) between all living things and the environment) through the development of an “interconnected ecological knowledge system.”

Time is not on our side. The UN International Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) in its latest report has warned that unless we limit global warming to 1.5C. and cut carbon emissions by 43% by 2030 the world is on course for catastrophic warming of 3.2 C by the end of this century. Biodiversity loss, emerging infectious diseases, such as Covid-19, and geopolitical tensions are also at the forefront of global crises in this decade, which must surely lead us to question our fundamental relationship to the planet and to each other.

Because of subject-matter scope, the paper is being published by PEAH in three parts over few weeks span:

Part 1: The One Health & Wellbeing Concept

Part 2: Development of a Global ‘All Life’ narrative

Part 3: The international One Health for One Planet Education Initiative (1 HOPE) and the ‘ecological university’

![]()

By George Lueddeke, PhD

Consultant in Higher, Medical, and One Health Education

Global Lead – International One Health for One Planet Education initiative (1 HOPE)

Reflections on Transforming Higher Education for the 21st Century

BRINGING ‘SHARED VALUES TO LIFE’

Part 3: The international One Health for One Planet Education Initiative (1 HOPE) and the ‘Ecological University’

Part 1: The One Health and Wellbeing Concept

Part 2: Development of a Global ‘All Life’ Narrative

The folly of a limitless world

In the Living Planet 2014 report, Dr Marco Lambertini, director general of Worldwide Wildlife Federation (WWF) International, gently reminded that given the state of the world including a huge drop (c. 50%) in population sizes of vertebrate species, “We need a few things to change.” These included finding “unity around a common cause,” public, private and civil society “to pull together in a coordinated effort,” and “leadership for change“ especially for “Heads of state to start thinking globally” and along with “businesses and consumers …to stop behaving as if we live in a limitless world.” He called for the world to “stop and think” about the kind of future we are heading for.”

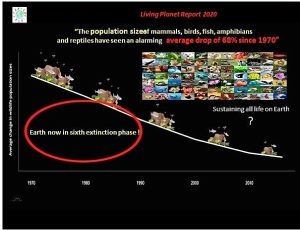

In the intervening seven years, the decline of species has continued and globally, as the Living Planet 2020 report confirmed, now stands at 68 percent (Figure 6) with the highest drop in South America and the Caribbean at 94 percent. The world is indeed “in trouble,” underscored by the International Panel on Climate Change (IPPC) 2021 report .

A short article, entitled ‘Silent Earth: The decline in insect life is a threat to the survival of humans and all living species’ focused on insects, which account for more than half of all species on the planet (c.8.5 million) and are “in precipitous decline” about “ 34 per cent a decade.” The consequences are startling: “the world would soon run out of food. Not enough crops could be grown to the feed the world. The world would become barren. The extinction of bird species would accelerate.” Humankind continues to be responsible (irresponsible?), as stated in the piece, and while farmers are now spraying crops and apparently are using pesticides sparingly, “The toxic load grew sixfold between 1990 and 2015.”

Figure 6: Decline of species across the globe

(Source: COP26 presentation: Tackling the Root Causes of Climate Change, 2021)

Global and national organisations are commended for their resolve to strengthen equity, access and quality through meetings, conferences and reports leading to specific statements of intent and recommendations since the launch of the UN-2030 SDGs. These include the UN – 2030 SDGs (2015), the Incheon Declaration for Education 2030 (2015-based on SDG 4), UNESCO’s education mission (2017), the Commonwealth Education Policy Framework (2017), the World Bank Group ‘World Development report 2018,’ and the OECD Education 2030 initiative (2018).

During these years, funding of education became a top priority, including a high-level event in 2017 during the seventy-second session of the UN general Assembly in New York: “Financing the future: Education 2030” highlighting, as one example, that globally “130 million girls are out of school today…pushing back against poverty, war and child marriage to go to school” and the urgency to “invest in girls.” UN Secretary General Guterres emphasised that “investing in education is the most cost-effective way to drive economic development, improve skills and opportunities for young women and men, and unlock progress on all 17 Sustainable Development Goals.” These comments were echoed by the former UK Prime Minister and UN Special Envoy for Global Education and UN Education Commission Chair, Gordon Brown, stressing that “Delivering an education for all-and not just some children is the civil rights struggle of our time” especially in light of the refugee crisis then and now exacerbated by the war in Ukraine and conflicts elsewhere.

Perhaps the incoming Director-General of UNESCO and former French Minister of Culture and Communication, Audrey Azoulay, said it best in 2017 in her investiture speech highlighting:

“The challenges posed by to the world today by environmental degradation, terrorism, attempts to discredit scientific findings, attacks on cultural diversity, the oppression of women and the massive displacement of populations,” necessitating “the need for concerted strategies in the framework of multinationalism to face the challenges today and tomorrow.”

The Minister’s theme was well captured in the OECD The future of education and skills 2030 project in 2018 which put forth that education was “more than getting a good job and high income” but “the need to care about the well-being of their friends and families, their communities and the planet.”

Education and research for the 21st century

As discussed in this article, to address climate change, biodiversity loss and avoid a repeat of the pandemic, the shift from human-centrism (anthropocentrism) – ’it’s all about us’- to eco-centrism – ‘it’s about all species, including us, and relationship to the planet – is profound. Taking on board the One Health and Wellbeing concept, Earth Charter values and principles and the UN Sustainable Development Goals could make the difference between planet sustainability and a dystopic world.

Whether we are able to achieve a “more just, sustainable and peaceful world” will depend on the decisions we make now as opportunities for social transformation are becoming increasingly time- limited. There is no question that new thinking is required and that both education and research are key in moving societies in new directions to ensure planet sustainability. To these ends, here are a few re-orientations to consider by governments, corporations and civil society in general to sustain life on the planet shifting from:

- Human-centrism to eco-centrism;

- subject fragmentation to disciplinary integration;

- knowledge transfer to knowledge discovery;

- intervention to prevention and a future consciousness;

- individualism to ‘learning from and with others’:

- those who ‘have‘ to those who ‘have not’;

- thinking globally to acting locally;

- profit margins to self-fulfilment and ‘doing something good’;

- self-interests, ambition, power to understanding, compassion and truth.

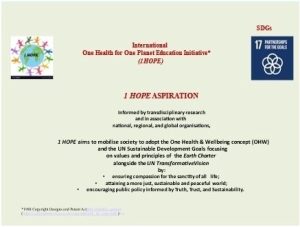

The international One Health for One Planet Education initiative (1 HOPE)

Transformations in the preceding paragraph reflect the importance, as UNESCO contends, for an “education” that is “transformative” and that cultivates “an active care for the world and for those with whom we share it.” In Part 2 of this article a similar argument was made for today’s research priorities.

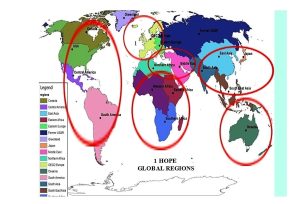

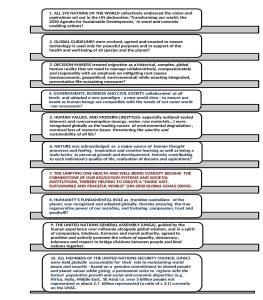

1 HOPE originated with ‘Ten Propositions for Global Sustainability’ (Annex), outlined in Survival: One Health, One Planet, One Future , and in particular Proposition #7 which called for consideration of the One Health and Wellbeing (OHW) concept becoming “the cornerstone of education systems and societal institutions” underpinning the UN-2030 SDGs. In 2018/19 several working groups (education and governance) were established by the One Health Education Task Force, hosted by two leading One Health organisations, the One Health Commission (OHC), and the One Health Initiative (OHI), to take forward the One Health concept and the SDGs in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and the Americas. While spearheaded by dedicated and highly experienced colleagues in these regions (Higher Education at the University of Global Health Equity [Rwanda] and Primary/Secondary Education at the University of Yaoundé [Cameroon]) , implementation proved to be challenging partly because of the need to (1) create greater awareness of I HOPE across highly populated regions and build concept understanding and ‘ownership’; (2) engaging cross-disciplinary working group members; (3) reconciling competing time pressures / university priorities; (4) funding/infrastructure to support planned pilot activities; and (5) the emergence of Covid-19. Considered collectively, these difficulties necessitated a comprehensive review of 1 HOPE building on OHC/OHI progress and leading to the formation of sub-regionally-focused planning teams (Africa , Americas, Asia, Europe, Oceania) while continuing to raise awareness of 1 HOPE (IPR) and the SDGs as integrative concepts and approaches globally in association with various organisations. In the past year, these have included, among others, the University of Pretoria/Future Africa, the Indian Regional Association for Landscape Ecology, the International Student One Health Alliance, GIZ-HWC, the International Veterinarian Students’ Association, Afrique One–ASPIRE, One Health Lessons, the CORE Group, the All India Institute of Hygiene and Public Health, and COP-26.

Further to regional consultations during 2021/2022, consortium planning groups have to date generally agreed on five ways forward:

- focusing on priority concerns or needs at regional or sub-regions levels;

- adopting the main 1 HOPE aspiration and regional involvement (Figures 7 & 8), informed by the OHHLEP definition of One Health (Part 1);

- establishing regional consortia led by ‘university – affiliate’ planning teams with representatives drawn from a cross-section of disciplines and societal sectors (civil, gov’t, business);

- strengthening collaborations with existing regional organisations engaged in addressing immediate and longer-term risks or problems related to present and future global sustainability; and

- considering the formation of a global 1 HOPE ‘advisor forum’ to guide regional strategic planning.

Figures 7 & 8: The international One Health for One Planet Education initiative (1 HOPE)

(Source: Rebuilding Trust and Compassion in a Covid-19 World, 2021)

University leadership: Towards the ecological university

In his book The Ecological University: A Feasible Utopia, Emeritus Professor Ronald Barnett at the UCL Institute of Education reminds us that our ‘responsibility’ is steeped in values and matching these for the 21st century and to mass higher education remains a major gap.

He concludes that our university “knowledge ecosystem” is impaired – too bounded, too imbued with the interests of the powerful –and with limited levels of critical reason.” Mirroring the interconnection and indivisibility of the SDGs, the author proposes a new university “knowledge ecology (symbiotic relationship between all living things and the environment) and the development of an “interconnected ecological knowledge system” that recognises six different regions of knowledge or zones: knowledge, learning, culture, persons, society more broadly, and the natural world. Of these, the author maintains that economics has become the most dominant in universities. However, as this article highlights, climate change has now become the most serious global risk, demanding identifying root causes and mitigating their impact on the planet and all species. From educational, research and community perspectives, we are now tasked to take a much more holistic view of the world, assumptions, beliefs, practices and the urgency, as Professor Kuiken argues, to pay “equal attention to the health (and wellbeing) of ecosystems, animals, and humans” while ensuring that environmental boundary conditions are not transgressed. In short, Professor Barnett calls for “a new kind of knowledge management” that “engages with the world,” and where “university leaders” become “active epistemologists” – “ethically oriented and imbued with a concern for the whole Earth.”

This shift in global priorities has significant implications for education and research encouraging policy-makers to re-think the purpose and priorities of societal institutions, including universities and schools (Annex). The SDGs have shown the way by making us aware of the interdependency of human activity and collective impact on the planet along with the need to re-structure education systems to integrate these realities through the developments of interconnected ecological knowledge systems with a concern for the whole Earth. A hallmark of this transformation would be to foster integrative thinking and helping learners / researchers to find their way through disconnected bodies of information and perspectives including finding ways to curb society’s huge appetite for exploitation, brutal competition and conflict.

In this regard, Professor Jeffrey Sachs, president of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network, referencing the SDSN Leadership Council Statement on the War in the Ukraine, recently noted the “heightened responsibility educators and university leaders” have in better preparing students to face and help address these unimaginable and devastating situations. His key message resonated with the main themes of this article underscoring that universities “must teach not only scientific and technical know-how to achieve sustainable development, as important as those topics are today, but also the pathways to peace, problem solving, and conflict resolution.”

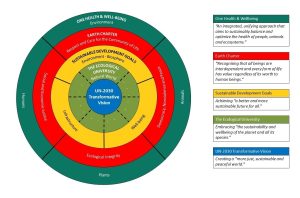

With the latter in mind, Figure 9 illustrates how concepts and constructs discussed in this article might be brought together as a conceptual framework in the development of the ‘ecological university’ based on the underpinning the values of the One Health and Wellbeing concept and basic principles of the Earth Charter to inform the UN-2030 SDGs in order to achieve the UN Transformative Vision.

Figure 9: A conceptual framework for building the ecological university

Considerations for transformative change and global sustainability

As things stand, we are facing unprecedented global risks – climate change, biodiversity loss, emerging diseases, geopolitical tensions, to name several threats, while also seeing an increasingly fractious, divided and dangerous world.

Dr. Marco Lambertini, Director General of the WorldWide Fund for Nature International (WWFI) challenged us several years ago to respond to three main questions:

- “What kind of future are we heading toward?”

- “What kind of future do we want?”

- “Can we justify eroding our natural capital and allocating nature’s resources so inequitably?”

William Joy, an American computer scientist, posed similar queries in Why the future doesn’t need us providing the main rationale for doing so, that is: if we could agree “as a species, what we wanted, where we are headed, and why, we could make our future much less dangerous and then might understand what we and should relinquish.”

Concluding comments

After billions of years of evolution, in just a few decades we have come to an inevitable turning-point. While we have made significant scientific / technological progress, we have failed to safeguard life on the planet including ours (we are but one of about 8.5 million species!). Although we have cognitive and affective capacities for achieving a harmonious world, our lives continue to be overridden by the self-interests, ambitions, and power of a few (1%?) -think AI and technology!

In the longer run, it appears that “a more just, sustainable and peaceful world” can only be achieved if we all realise the consequences of our short-term thinking (e.g., profits over survival, control or enslavement over freedoms) and learn to rise above the human-fabricated divisions and inequities that divide us (social, political, religious, economic, etc.). If we fail, so will future generations and humanity. Democratic societies depend on a shared belief in ‘something greater than themselves’ and holding ‘power to account’.

The United Nations, including the Youth Forum ,and Higher Education have pivotal roles to play in safeguarding our democratic freedoms. The UN, “the world’s largest universal multilateral international organisation” has offices in 193 countries and 37,000 employees, and there are over 90,000 institutions and 200 million students across higher education. With their immense outreach capacity, knowledge base and combined leadership synergy, they are in a prime position to raise awareness that ‘the one thing we have in common is our planet’, that major societal transformations are required – compassion, empathy trust for global sustainability, and that making the world work better is our greatest challenge. The younger generation has the most to gain by raising their collective voice about global sustainability but also the most to lose by not doing so. As Nelson Mandela, former president of South Africa said several decades ago: “Sometimes it falls upon a generation to be great. You can be that generation. Let your greatness blossom.” Now is the opportunity for doing so and meeting the challenges set by the 126 Noble Laureates in their Our Planet, Our Future’ Statement and delivered to world leaders ahead of the G-7 Summit in 2021.

“Ultimately,” Emeritus Professor of Neurology Dr. David Wiebers at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, USA reminds us: “the survival not only of other species on this planet, but also of our own, will depend upon humanity’s ability to recognise the oneness of all that exists, and the importance and deeper significance of compassion for all life.”

The choice is ours!

Annex

Figure 10: Ten Propositions for Global Sustainability

WHAT IF?