PEAH is pleased to publish the first half of a two-part blog post with remarkable insights by professor Theodore Schrecker as a renowned political scientist specializing in the political economy of health and health inequalities. Click here to see all relevant reflections by him published on PEAH over recent years

Emeritus Professor of Global Health Policy, Newcastle University

The Covid-19 Pandemic as Tipping Point (Part 1)

I began a (pessimistic) 2022 book chapter on the prospects for ‘building back better’ after the Covid-19 pandemic by quoting the first sentences of J.G. Ballard’s magnificent dystopian novel High-Rise:

Later, as he sat on his balcony eating the dog, Dr Robert Laing reflected on the unusual events that had taken place within this huge apartment building during the previous three months. Now that everything had returned to normal, he was surprised that there had been no obvious beginning, no point beyond which their lives had moved into a clearly more sinister dimension.

The giveaway word here is “normal,” and the new normal to which Laing’s world has returned is one in which a deadly class war between the affluent and even more affluent residents of a 40-story tower block has completely destroyed the interior of the building and most of its vital systems, and survivors are reduced to killing and eating the pets of their less fortunate neighbours. In a scene near the end of the novel, surviving children play with human bones in the tower block’s rooftop sculpture garden.

This rather dramatic introduction was designed not to suggest that post-pandemic societies will literally regress to that extent, although that could happen in some contexts, but rather that conditions of life that come to be regarded as normal in the post-pandemic world will probably look very, very different from those of late 2019, and for most of us more insecure and threatening. I am more convinced of this now than I was when I wrote the chapter.

In a recent conference paper, I argued that the pandemic should be understood as a tipping point, initiating processes that magnify and accelerate existing trends, in particular those involving rising inequality and its direct and indirect effects on health. The concept of a tipping point is used in several, slightly different ways depending on context, but it is now most familiar from research on climate change. Leading climate researcher Timothy Lenton explains: tipping points “occur when there is strongly self-amplifying (mathematically positive) feedback within a system such that a small perturbation can trigger a large response from the system, sending it into a qualitatively different future state.” Stated more colloquially, “sometimes little things can make a big difference,” or at least a disproportionate difference, “to the state and/or fate of a system.”

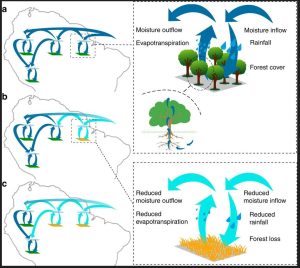

Figure 1. Schematic representation of cascading effects in the vegetation–rainfall system

(a) Vegetation–atmosphere system in equilibrium. (b) Initial forest loss triggered by decreasing oceanic moisture inflow. This reduces local evapotranspiration and the resulting downwind moisture transport. (c) As a result, the rainfall regime is altered in another location, leading to further forest loss and reduced moisture transport. Reproduced without change from Zemp, D. C., Schleussner, C. F., Barbosa, H. M. J., Hirota, M., Montade, V., Sampaio, G. et al. (2017). Self-amplified Amazon forest loss due to vegetation-atmosphere feedbacks. Nature Communications, 8, 14681 under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence.

An especially striking example is provided by deforestation in large tropical rain forests (Figure 1). As much as half of the precipitation that falls on such forests originates from evapotranspiration within the forest itself. The concern is that deforestation resulting from human activity (forest clearance) will combine with reduced oceanic moisture inflows to lead to a tipping point in which reduced rainfall accelerates forest dieback, and the rain forest transitions to savannah or steppe. This will itself accelerate climate change, as the forest no longer provides a carbon sink. Researchers write that findings about multiple processes of this kind “imply that shifts in Earth ecosystems occur over ‘human’ timescales of years and decades, meaning the collapse of large vulnerable ecosystems, such as the Amazon rainforest and Caribbean coral reefs, may take only a few decades once triggered.” This is a long time in the context of such phenomena as election cycles, but an eyeblink in geological time. Whatever the time scale, once a tipping point has been reached, the pace of changes that were already under way accelerates rapidly, and entirely new changes may begin.

My pre-retirement colleague Clare Bambra and colleagues have provided an especially compelling account of how distribution of health outcomes during the pandemic reflected and magnified economic inequalities (open access, and essential reading). Looking ahead, here are a few of the patterns (far from an exhaustive list) that suggest the value of considering the pandemic as tipping point:

- Concentration of wealth at the very top of national and global economic distributions: The number of US dollar millionaires worldwide increased from 46.8 million in mid-2019, the last pre-pandemic year, to 62.5 million in 2021. This growth was fuelled by rising share prices, but also by

- Soaring property prices in much of the world. US homeowners saw their wealth increase by more than US$6 trillion between the start of the pandemic and the third quarter of 2022; average house prices across Canada’s 15 major metropolitan areas rose by as much as 45 percent between 2019 and 2021, depending on distance from the city centre. The ‘flip side’ of this pattern, which began before the pandemic but was accelerated by it and is repeated in many European centres, is

- A growing pattern of unaffordable housing and semi-permanent housing insecurity, underpinned by the financialization of housing, which also predates the pandemic and led one group of Australian researchers to conclude that: “sustained inflation of property values … has fundamentally shifted the social class structure, from a logic that was structured around employment towards one that is organized around participation in asset ownership and appreciation.”

- Housing prices are an important part of a larger cost-of-living crisis, originating in supply chain disruptions associated with the pandemic and worsened by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its weaponization of energy exports. Interest rate increases – a conventional central bank inflation-fighting tactic – cannot address these impacts because they have no effect on supply, and in fact are likely to magnify inequality, as they raise the cost of consumer debt and are passed through to consumers by producer firms.

- In a global frame of reference, countries differed in the fiscal capacity they were able to deploy in initial responses to the pandemic, which will probably lead to increased inter-country inequality. Further issues arise from what could be

- An impending sovereign debt crisis for many countries; before the pandemic the sovereign debt load of countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the world’s poorest region, was more than twice its nominal value in 2009, the year after the financial crisis. In early 2023 the American Public Health Association called on the International Monetary Fund, World Bank and G20 “to eliminate debt for the poorest countries and expand fiscal space for public financing of health services and public health programs.”

- Finally, of course, there are the effects of climate change on various social determinants of health, including food security.

The World Economic Forum’s 2023 Global Risks Report devoted an entire chapter to the concept of “‘polycrisis’ – a cluster of related global risks with compounding effects, such that the overall impact exceeds the sum of each part.” This is a useful way of capturing the interactions discussed here, yet at the same time we must acknowledge that many trends in question will present as crises for many, and opportunities for others. (Housing price escalation is a case in point.)

Perhaps my view of the future is excessively bleak. After all, high-income countries were able to buffer many of the pandemic’s economic effects, and the US improbably experienced a substantial, if temporary, drop in poverty. The situation outside the high-income world was, and is, considerably more grim, like the “vaccine apartheid” that has now largely faded from public consciousness reflecting the multiple dimensions of global inequality and the relative invisibility of the global majority. Numerous blueprints, some quite detailed, exist for ‘building back better’. The second part of this posting will direct readers to a few of these; assess some of the formidable political obstacles to their realization against the background of rising inequality; and offer a few conjectures about health in the post-pandemic new normal.