IN A NUTSHELL Author's NoteAs part of a series, a new analysis here calling for subnational data and analysis to render higher sensitivity in identifying ethical efficient human models and in estimating the burden of failing to adjust our lifestyles and human dynamics to sustainable wellbeing patterns

By Juan Garay

Professor of Global Health Equity Ethics and Metrics in Spain (ENS), Mexico (UNAChiapas), and Cuba (ELAM, UCLV, and UNAH)

Co-founder of the Sustainable Health Equity movement

The Price of Global Injustice in Loss of Human Life

Update of the Analysis of the Global Burden of Health Inequity 1961-2023

1947 WHO’s constitutional goal—achieving the best feasible health for all people[i] is the only globally shared health objective among nations. However, it is not measured by WHO or any government despite the 2009 World Health Assembly commitment to do so[ii].

Failing to identify the best feasible level of health leaves the partial analysis of health inequalities by arbitrary variables as the global reference of health justice monitoring[iii] fueling the fragmentation of health views and actions[iv].

Previous articles this year have used the recent UN Population 1950-2023 population and mortality estimates and 2024-2100 prospects to update the ethical ecological sustainability thresholds—1.42 hectares per capita for biocapacity and ecological footprint[v], and 1.34 metric tons of CO2 emissions per capita[vi]. Only 16 countries have constantly held footprints per capita respecting nature´s recycling capacity constantly from 1961-2023[vii]. All countries with GDP pc above the world average (measuring the economic transactions and their relation with production, trade and consumption) disrespect planetary boundaries, regardless technological advances and often rhetorical global commitments. Amongst the ecologically sustainable countries, only one has levels of life expectancy, that being above the world average, can inspire the world to progress in wellbeing while respecting its resources for coming generations: Sri Lanka. It uses less than half the world’s average economic resources per capita and only 12% of the world average health spending per capita, yet enjoys 10% higher of life expectancy. The international data have major limitations and hide major subnational disparities. The present analysis calls for subnational data and analysis to render higher sensitivity in identifying ethical efficient human models and in estimating the burden of failing to adjust our lifestyles and human dynamics to sustainable wellbeing patterns. Preliminary analysis of larger countries suggests subnational references in some regions of India, China, Russia, Indonesia, Pakistan, Brazil and Bangladesh[viii]. None of the European Union countries, USA states and other OECD countries respect planetary boundaries, and their “development” references, as the human development index ranking, guides towards human self- and nature´s ecocidal destruction[ix].

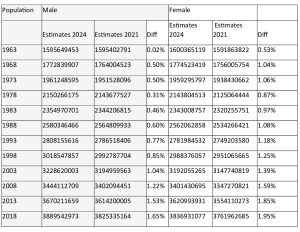

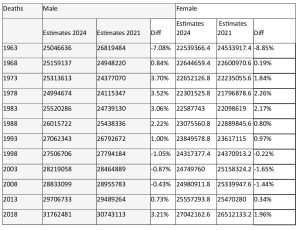

From 2011 to 2021 we have used international data from the world bank, the global footprint network and the world health organization, to select sustainable wellbeing references. As the UN used to publish population and mortality estimates every five years, we estimated the number and proportion of excess deaths from the mentioned references for the periods 1960-2010[x] (book[xi] ), -2015[xii] (book[xiii]) and -2020[xiv] (online atlas[xv]). Up to now, the data were the average of 5-year periods and were disaggregated by country, sex and 5-year age groups. The 2024 revision has been upgraded from 5-year periods to annual time series, and from 5-year age groups to single ages[xvi] and revised retrospectively the full time series since 1950. It incorporates a systematic and comprehensive set of mortality crises for all countries/areas since 1950 and includes excess mortality attributable to COVID-19 in 2020-2021 and since then. The changes are substantial, as the tables below show.

Table 1 World population prospects´ changes from 2021 to 2024 UN reports

Table 2 World deaths estimates´ changes from 2021 to 2024 UN reports

In countries like China they relate to the major historical demographic changes experienced during the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution and one-child policy periods that have affected population cohorts. Given their share of the world population, those changes have a significant impact on the overall world demographic data update.

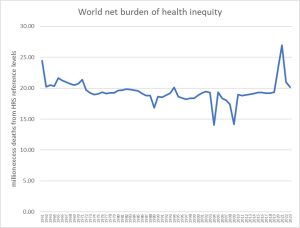

With the mentioned updated UN population data, we estimated the annual mortality rates from 1950-2023 by single year age groups and sex and the differential mortality rates with the healthy-replicable-sustainable -HRS- health (best feasible health) reference (6.6 million data each). We then applied the differential mortality rates to the reference population of each country and group and selected those in excess in each case (again 6.6 million data) to calculate the net burden of health inequity (nBHiE). The following graph represent the world´s aggregate data:

Figure 1 World net burden of health inequity

Since 1963 the number of deaths in excess from the best feasible and sustainable levels of health (shared global health objective since 1947´s WHO constitution) has been around 20 million, 20.18 million in 2023. The acute fluctuations between 2004 and 2009 relate to high adult mortality during the civil war in Sri Lanka, the HRS reference, while the peak in 2020-2021 reflect the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

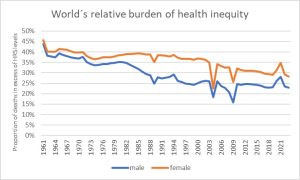

To better compare countries, age and sex groups, we calculated the proportion of all deaths that were in excess of the best feasible (HRS) levels, that is, the relative burden of health inequity (rBHiE). See rBHiE world data in the following graphs:

Figure 2 World Relative burden of health inequity 1961-2023

The graph above shows how the proportion of all deaths explained by global social/health injustice/inequity, has decreased in men from 45% in 1961 to some 25% in the 90s and remained quite stable since then, allowing for the acute fluctuations mentioned above in the nBHiE. As for women, the levels remained around 40% until the turn of the century and have decreased to some 30% in the last two decades with the mentioned fluctuations.

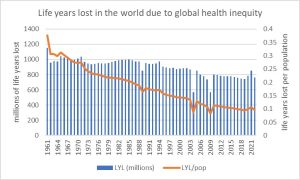

To calculate the human life years lost due to health inequity (LYLxHiE), we multiplied each excess death (nBHiE) by the difference of the age it took place with the HRS life expectancy at that given age group, sex, and year. The total number of life years lost due to global health inequity is represented in the following graph as well as the proportion of human life lost per person.

Figure 3 Life years lost in the world due to global health inequity

The representation of the life years lost due to global health inequity reveals a stable figure around 800 million since the turn of the century, with the acute fluctuations explained above. The proportion of potential human life (best feasible level) lost each year due global inequity/injustice has gradually decreased from 30% in 1961 to around 10% in 2023, as the median age of each excess death has increased due to the reduction of under five mortality in the last 62 years.

Conclusions: the recent UN population update, together with the estimates of carbon budget before we hit the 1.5º global warming enable the identification of the carbon footprint pc ethical threshold. Such carbon ethical threshold together with the world average biocapacity pc and ecological footprint serve as the ecological sustainability criteria which selects only 16 countries that have been constantly respected nature´s recycling capacity. No country with macroeconomic indicators of GDP/GNI measured in CV/PPP pc and wealth pc above world weighted average met the sustainability criteria. Among those ecologically sustainable and economically replicable countries, only one country had constantly a life expectancy at birth, both for women and men, above world average since 1961, and healthy life expectancy (deducting the burden of disability) above world average since measured in 1990. Such country is Sri Lanka, which hosts only 0,2% of the world population. Having only one HRS reference means that its fluctuations in mortality rates, as experienced during the civil war, impact the estimates of the burden of health inequity. As mentioned above, when looking at subnational regions in the 10 countries with higher population (representing 60% of the world population), we could see, only for the last 5-year period average data on life expectancy and GDP pc at CV/PPP, highly correlated with carbon emissions and ecological footprint especially when considering the consumption dimension, that 22 subnational regions representing some 6% of the world population may meet the HRS criteria. A detailed analysis of the world’s approximately 80,000 districts will likely uncover the most efficient and sustainable models rendering much higher sensitivity to the analysis of the burden of health inequity, its distribution and the identification of features (social, political, economic, cultural and environmental) that enable equitable and sustainable (fair) human well-being[xvii].

References

[i] https://www.who.int/about/governance/constitution

[ii] https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/2257

[iii] https://www.who.int/data/inequality-monitor

[iv] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)32072-5/abstract

[v] https://www.footprintnetwork.org/

[vi] https://www.peah.it/2024/07/13556/

[vii] Afghanistan, Burundi, Benin, Burkina Faso, Comoros, Haiti, Kenya, Cambodia, Sri Lanka, Malawi, Niger, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines and Rwanda

[viii] India (Kerala, Nagaland), China (Shanxi, Guangxi, Anhui, Sichuan, Henan), Russia (Ingushetia, Chechnya, Kabardino, Dagestan, Karachay in the North Caucasus), Indonesia (Sulawesi, Kalimantan, Bali, Java), Pakistan (FATA), and Brazil (Piaui, Alagoas, Paraiba, Ceara, Para, Rio Grande do Norte)

[ix] https://www.peah.it/2024/09/13667/

[x] https://www.peah.it/2015/10/understanding-measuring-and-acting-on-health-equity/

[xi] https://www.binasss.sa.cr/eng.pdf

[xii] https://oxfordre.com/publichealth/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.001.0001/acrefore-9780190632366-e-62.

[xiii] https://my.editions-ue.com/catalogue/details/fr/978-3-330-86865-6/the-ethics-of-health-equity

[xiv] https://www.peah.it/2021/04/9658/

[xv] https://gobierno.uniandes.edu.co/es/Noticias/atlas-medici%C3%B3n-equidad-salud

[xvi] https://population.un.org/wpp/Methodology/

[xvii] https://www.peah.it/2023/12/12800/

—-

By the same Author on PEAH

Identifying International Sustainable Health Models

Homo Interitans: Countries that Escape, So Far, the Human Bio-Suicidal Trend

Human Ethical Threshold of CO2 Emissions and Projected Life Lost by Excess Emissions

Restoring Broken Human Deal

Towards a WISE – Wellbeing in Sustainable Equity – New Paradigm for Humanity

A Renewed International Cooperation/Partnership Framework in the XXIst Century

COVID-19 IN THE CONTEXT OF GLOBAL HEALTH EQUITY

Global Health Inequity 1960-2020 Health and Climate Change: a Third World War with No Guns

Understanding, Measuring and Acting on Health Equity