IN A NUTSHELL Author's NoteThe aim of this study is to explore the extent to which barriers at the NHS level are impeding the entry of International Medical Graduates (IMGs) into the health system in the UK. Specifically, we try to shed light on the factors contributing to the ongoing medical workforce crisis in the UK despite high demands for jobs in part of IMGs

By G. Zangana, C. Flores, A. Elseraty, T. Wardani

Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh

Navigating the Labyrinth

Addressing the Structural Challenges for IMGs in the UK Healthcare System

Introduction

The world is currently facing a severe shortage of healthcare workers, with the World Health Organization (WHO) projecting a global shortfall of 10 million health workers by 2030 (1). This crisis is most acute in low- and middle-income countries, but it also affects higher-income nations such as the United Kingdom (2). In the UK, the ratio of doctors to the population is significantly lower than the EU OECD average of 3.7 doctors per 1,000 people (3). England alone requires an additional 50,000 full-time doctors to meet this standard. As of June 2024, there were 10,745 medical vacancies in secondary care in England, representing about 7% of all medical positions (4). Furthermore, 59% of UK consultant physicians reported at least one vacancy within their departments, highlighting the widespread impact of this shortage on the nation’s healthcare system (5). The UK is attempting to address this shortage in its healthcare workforce through improving internal recruitment and training (6). However, this is unlikely to completely solve the problem. As a result, the UK has resorted to recruiting internationally trained doctors and nurses (7). Currently, the UK is one of the largest recruiters of International Medical Graduates (IMGs).

In recent years, more doctors who earned their medical qualifications outside the UK have been applying for jobs within the country. According to the General Medical Council’s (GMC) “Workforce Report 2023,” international medical graduates (IMGs) now make up 52% of the UK’s medical workforce (8). According to the same report, since 2017, the number of IMGs in the UK has surged by 121%. However, many IMGs struggle to secure jobs, with only a fortunate minority successfully navigating the application process, leaving a significant number turned away. Understanding the challenges these doctors face when seeking their first NHS role is crucial.

While there is considerable literature on the difficulties IMGs encounter once employed, such as the need for better induction programs, mentorship, and clinical supervision (9–12). However, very little research addresses the barriers IMGs face when initially applying for NHS jobs. One article explored the aspiration of unemployed doctors who are in the UK on dependent visas (13). Another examined similar issues for refugee doctors only (14). This gap in knowledge prompted us to explore the specific challenges faced by IMGs already in the UK as they try to secure their first position as medical doctors in the NHS. The aim of this study is to explore the extent to which barriers at the NHS level are impeding the entry of IMGs into the health system in the UK. Specifically, we try to shed light on the factors contributing to the ongoing medical workforce crisis in the UK despite high demands for jobs in part of IMGs.

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Method

We used a mixed method approach to address the aim of this paper. We started our enquiry with a review of the existing literature on this topic. We conducted a comprehensive literature review using the Ovid, PubMed, and Google Scholar search engines to explore the challenges IMGs face in securing their first job within the NHS. The search strategy employed keywords such as “international medical graduates,” “IMG,” “overseas doctors,” “UK,” “NHS,” and “challenges,”, “first job”, with results limited to English-language publications from the last ten years. This search yielded studies that examined various aspects of IMG experiences, including the barriers to entering the NHS workforce, the impact of differing healthcare systems on IMGs’ preparedness, and the strategies used to overcome these obstacles. Insights from this review informed the focus group discussions and helped contextualise the challenges reported by IMGs.

Our informal communications with IMGs highlighted the existence of social media groups with rich data about IMG experiences in this area. We identified one IMG Facebook group that has 151.2K members. We reviewed the comments published in this group and summarised the most common challenges and feelings that colleagues mentioned in this group regarding landing their first job in the NHS.

Second, we conducted a survey amongst IMGs. We used Google form for this purpose. We distributed our survey to a WhatsApp group of 298 IMGs. Our main goal was to understand the most common challenges for IMGs when applying for their first job in the last 10 years and how they overcome these challenges, if possible.

Finally, we used the results of the survey to inform discussions in one focus group interview with key informants within the same IMG community. Seven participants (4 in person and 3 online) took part in the discussions. Personal experiences were shared by participants. The proceedings of the focus group interview were documented and then analysed thematically to identify major themes related to challenges and opportunities for obtaining a job in the NHS.

To determine the ethical requirements for this study we undertook the Medical Research Council’s online tool to determine whether it is a research ethics approval. It was determined that this study does not require formal ethical approval. However, we also sought advice from the ethics committee of the local NHS trust that deemed it as a service improvement project and hence not requiring ethical clearance.

Results

Navigating the NHS’s job market and its frustrations for IMGs

A review of comments from an IMG-focused Facebook group and a survey amongst IMGs revealed several recurring themes regarding the difficulties international doctors face in securing NHS jobs.

A prevalent challenge was the widespread perception amongst IMGs about the limited availability of vacancies and the overall saturation of the job market. Many reported submitting between 100 and 500 applications each, often receiving either a rejection or no response at all, despite believing their CVs were strong.

These findings were underscored by the focus group participants. According to them, a common approach involves applying for NHS staff bank positions, which are viewed as a stepping stone to obtaining substantive roles. However, many participants expressed frustration with the slow responsiveness of staff banks, which often delayed their entry into the NHS workforce. Some IMGs reported submitting over 200 job applications before securing a position, illustrating the persistence required to succeed in such a competitive environment. Feedback on applications, when provided, was considered highly beneficial by participants, though they noted the inconsistent and sporadic nature of these responses from employers.

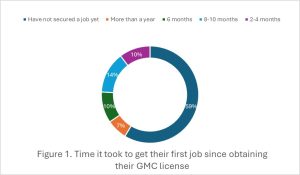

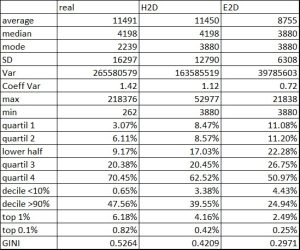

As a result, it takes IMGs long periods of time to get their first job since obtaining their full licence here in the UK (Figure 1.), the majority of respondents of our survey indicated that they had not secured a job yet, with six people already looking for a job between 5 and 12 months. Two out of 30 IMGs responded that securing their first job took them more than a year. Moreover, four replied that it took them between 8 and 10 months, followed by three colleagues who responded that it took them half a year. Only three IMGs confirmed that it took them 2 to 4 months to secure their first job after obtaining their licence, and only one has not started applying yet. Focus group participants also highlighted the long time it takes IMG to obtain a job. This time varied significantly, with some participants finding employment within two months, while others waited over a year. A recurring theme was that the first job is often the hardest to obtain, with IMGs encountering significant barriers during the initial stages of their job search. For some, this led to considering locum roles, though they found that many locum agencies required prior NHS experience, creating a catch-22 situation for those seeking their first opportunity. Others are working in ancillary jobs such as phlebotomist and careers in nursing homes. IMGs expressed concerns that they are de-skilled as a result of spending long periods of time away from clinical practice. Also, others highlighted the expensive cost of doing appraisal by private agencies which can get to up to £800 per appraisal as an excerpt from the email correspondence below indicates:

[… uses the L2P administration programme for appraisals which stands for Licence to Practise and is, we believe, the most intuitive system in the marketplace. It is simple to use and reliable. The cost of the appraisal and REV12 submission to the GMC is £620.00 + VAT (£744.00). We would require a £100 + VAT (£120.00) deposit and we can set you up on L2P. As this covers the L2P licensing costs, this amount is non-refundable if you do not complete your appraisal. The balance of £520.00 + VAT (£624.00) is payable prior to the allocation of an appraiser” [Recruitment Agency Staff_2]

A lack of prior NHS experience frequently emerged as a major barrier, as it is often listed as an “essential” criterion for many positions. For example, one Staff Bank sent the following response to an IMG seeking registration with them:

“Unfortunately, you need UK experience in the NHS to join the bank. Please look out for jobs on Jobtrain to gain UK experience and try again once you have gained some UK experience in the NHS” [Staff Bank Staff_1]

Another Staff Bank officer provided a more detailed response:

“The struggle that we have with the bank is we often get applicants with zero UK based experience whatsoever, we don’t necessarily require applicants to have quality NHS experience, it’s more that we would hope they’d have some UK based experience. As bank locums are often required to cover staffing shortfalls and can at times be the only doctor on duty for things such as HAN or on-calls, accepting someone on the Staff Bank with zero UK experience can be difficult” [Staff Bank_2]

Medical recruitment agencies expressed similar views. In an email to one IMG, a medical recruitment agency stated that:

“We do not have the opportunities available to offer doctors with no or limited NHS UK experience. Trusts are requesting a minimum of 6 months NHS experience.” [Recruitment Agency Staff_1]

Unpaid clinical attachments, a common means by which IMGs try to gain UK clinical exposure, were noted as not being recognised as NHS experience by many employers, further complicating the job search. The survey results also confirmed this difficulty. Out of the 30 responses for the first question, 47% of the colleagues answered that not having NHS experience was a challenge as most job posts ask for it as essential criteria. Some highlighted the challenge of not recognising a clinical attachment as valid NHS experience. Focus group participants also highlighted this difficulty by expressing frustration over the lack of consistency between NHS trusts in recognising clinical attachments as formal experience, with some trusts acknowledging them while others did not. This variability contributed to a sense of uncertainty about the value of these experiences. Focus groups participants also expressed frustration with the lack of transparency and consistency regarding clinical attachments also. The uncertainty about what would follow clinical attachments added to the stress of job-seeking, with some IMGs considering returning to their home countries to reapply from there.

A significant number of IMGs expressed frustration in the Facebook Group over the lack of guidance throughout the application process, particularly in relation to receiving feedback following an unsuccessful application. This lack of transparency left many applicants uncertain about how to improve their chances and move forward. Survey respondents expressed similar frustrations. Out of 30 respondents, 13 IMGs complained that they were not receiving an invitation for an interview, or they were receiving an “unsuccessful” email without feedback. It appears that this might be a factor in IMGs getting into jobs that are not their first choice or top preference. Disparities in job level assignments were another theme that emerged during the focus group discussions. Some IMGs found themselves being placed in positions that did not align with their experience levels, either being assigned roles below their qualifications or, in some cases, more senior roles than they felt prepared for. This created a feeling of mismatch and discomfort for those transitioning into the NHS. Many felt that the NHS recruitment system lacked empathy and fairness towards IMGs, which compounded the difficulties they faced in securing employment.

Additionally, the absence of audit or quality improvement project (QIP) experience was another critical obstacle. Many IMGs come from countries where these initiatives are not a routine part of medical education, yet they are essential components of NHS job requirements. This difficulty was highlighted by some survey respondents as well. Two responses included the challenge of needing a clinical audit or QIP experience when applying for a job. The focus group discussions also touched on deeper structural issues within the NHS recruitment system. Many participants expressed a sense of unfairness in how IMGs were treated, particularly regarding the emphasis on audits, quality improvement (QI) initiatives, and research. Since many IMGs come from healthcare systems where these activities are less common, they felt at a disadvantage compared to UK-trained candidates. There was a shared belief that the recruitment system placed too much weight on criteria that were not necessarily reflective of clinical competence. For example, the CREST form was viewed as redundant by some participants, as many of the competencies assessed had already been covered in the PLAB2 examination. The cost of obtaining qualifications, such as ALS or passing Royal College exams, was another point of contention, with several participants questioning why these additional expenses were necessary after already gaining GMC registration through the PLAB exams.

It appears that IMGs feel that there is a perceived preference for candidates holding dependent visas or indefinite leave to remain (ILR), added to the sense of disadvantage. In relation to this challenge, 2 IMGs mentioned that the lack of a long-term visa is an issue when getting some NHS experience. Staff Bank staff highlighted difficulties with visa requirements as well:

“Each applicant is unique though and we don’t automatically discount someone, the only time this would happen would be if they required a visa sponsorship as that isn’t something that can be provided via a bank posting” [Staff Bank Staff_2]

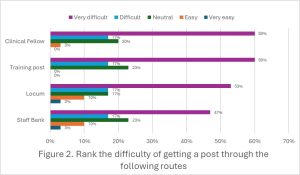

Additionally, we asked IMGs to rank the difficulty of getting a post through four different routes (Staff bank, Locum, Training post, and Clinical Fellow), using a scale from 1 to 5, with 1 being very easy and 5 very difficult (Figure 2.). For all routes, most considered it very difficult to get a job.

Overall, the commentary and survey results reflected a deep sense of hopelessness and frustration among IMGs, as the process of securing employment often proved to be more challenging than anticipated, even after obtaining their medical licence in the UK. These results also underscored the complex and multifaceted nature of the challenges facing IMGs in their efforts to secure jobs within the NHS.

Overcoming the impossible, landing the first NHS job for IMGs

The survey results and the focus group interviews with IMGs highlighted valuable insights into how barriers for getting a job in the NHS can be overcome. The discussions revealed that IMGs employ a variety of strategies to navigate the complexities of the NHS recruitment process.

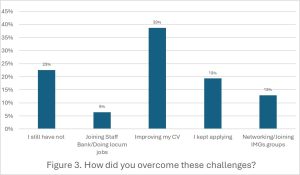

When asked about how they overcame the challenges of obtaining a job, 12 people responded that they overcame their challenges by improving their CVs (Figure 3). Similar recommendations for improving CV credentials were offered by focus group participants. In their view, this was done by taking further courses, such as Advanced Life Support, taking the Membership of the Royal Colleges exams, or doing clinical attachments. Some IMGs believed these credentials would enhance their job prospects, though they expressed frustration that this was not always the case. There were also concerns about qualifications like Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) (American accredited), with participants noting the unfairness of the NHS favouring ALS (British accredited), despite ACLS being similarly rigorous.

When IMGs were asked what could have helped them secure their first job faster, seven out of 30 replied they were unsure as they had not secured a job yet. Six colleagues responded that taking membership exams could help or getting more involved in clinical audits.

Online courses and resources emerged as essential tools for preparing for interviews and gaining a better understanding of NHS processes. These resources are particularly important for those unfamiliar with the NHS system, offering specific guidance tailored to UK medical practice. Similarly, clinical attachments were identified as a critical experience, providing opportunities for networking, skill development, and becoming familiar with NHS expectations.

Despite these efforts, participants highlighted areas where additional support could make a significant difference. Informal social networks, such as WhatsApp and Facebook groups, were heavily relied upon by IMGs to exchange information about job opportunities and share experiences. Four IMGs overcame their challenges by networking and joining different IMG groups, who advised them on how to apply for the NHS. Only two people mentioned they joined the staff bank or did locum jobs. While these platforms served as informal support systems, participants suggested the introduction of more structured networks to better facilitate the transition into the NHS. The participants also recommended improving staff bank responsiveness and providing clearer feedback on applications.

As part of our survey, IMGs were asked their opinions regarding how the NHS could improve its recruitment processes. There was a wide range of suggestions, the most common being changing the essential criteria of the “prior NHS experience”, as this was described as a significant barrier to IMGs. Some participants suggested considering the clinical experience in their own countries and the clinical attachments in the NHS as important experiences. Lastly, three out of thirty participants in this survey mentioned receiving feedback on unsuccessful job applications could be helpful for future applications. Some IMGs suggested applying through speciality exams rather than the PLAB route. Also, some advised that future IMGs should apply for jobs across the UK, being flexible location-wise, and do so before moving to the UK. A shadowing period of at least two weeks, during which IMGs could be supernumerary, was suggested as a helpful measure to support a smoother transition into the NHS.

Discussion

Highly educated migrant workers in the UK often face challenges in securing jobs that match their qualifications, leading to overqualification, where individuals work in roles beneath their skill level (15). This is particularly common among migrants from South Asia and certain European countries, driven by employers’ non-recognition of foreign qualifications, language barriers, and unfamiliarity with the UK job market (16). Studies have found that ethnic minority applicants also face discrimination during recruitment, with some needing to submit significantly more applications than their white counterparts to receive a positive response (17). This aligns with findings that IMGs, despite being highly skilled, often struggle to secure positions in the NHS due to similar barriers, including non-recognition of qualifications, lack of UK-specific experience, and implicit racial bias.

This study highlighted the difficulties that IMGs face in securing a job in the NHS due, at least in part, to the failure of regulatory agencies to recognise the qualifications they obtained in their countries of origin. This finding is consistent with similar observations made in other contexts such as Ireland (18). One IMG, known to the authors of this study, had to start as a foundation doctor even though they worked previously as the country director of an international non-governmental organisation in their continent. Many IMGs are required to undertake, for example, expensive and cumbersome English language tests, even though they have done medical school (and in some cases postgraduate degrees) in English. Others are required to obtain paperwork from agencies in their countries of origin in formats that are not possible to obtain. For example, one of the authors of this paper was required to obtain a letter of good standing from the regulatory agency in their country of origin by fax, a technology that is obsolete in that country.

It appears that by making it more difficult for IMGs (who are already in the UK) to enter the job market in the NHS, the latter is shooting itself in the foot. As this study made clear, IMGs face the risk of being de-skilled because of the long time they waste looking, unsuccessfully, for jobs. Clinical attachments are one way that IMGs try to gain experiences in the NHS (19). The British Medical Association appears to have issued guidance on clinical attachments (20). According to these guidelines, clinical attachments should offer the opportunity to internationally trained doctors to take history and examine patients. However, our own experience shows that those encounters are often not allowed. As a result, clinical attachments do not provide sufficient experiences needed for IMGs. Some trusts are also starting to charge for these clinical attachments (with some costing up to £400) (21). The charges levied add to the cost the IMGs need to cover related to their travel and accommodation during these attachments. The limited opportunities for clinical attachments that they might be able to access does not seem to offer much in the way of experiences that they need when they are eventually employed.

Beside these NHS related factors, wider structural barriers exist that prevent IMGs from obtaining jobs in the NHS. For example, the UK has prohibited bureaucratic visa sponsorship policies that require hospitals and GP clinics to issue certificates to IMGs to obtain visas (22). General Practitioner (GPs) trainees are particularly affected negatively by these rules (23). GPs training is 3 years and therefore most do not complete the minimum 5 years unless they go on maternity leave or change speciality.

Despite the significant obstacles, many IMGs demonstrated resilience through strategic applications, leveraging social networks, and improving their qualifications. However, there is a clear need for systemic changes to ensure a more equitable, transparent, and supportive recruitment process for IMGs. The discussions revealed a widespread perception of inequity within the system, with IMGs feeling that the heavy emphasis on research, audits, and specific qualifications created unnecessary barriers to entry. Many participants expressed a desire for a clearer, more unified recruitment strategy across the NHS. They recommended that the NHS be more flexible in its requirements for audits and QI, as these are not widely practised in many of the countries from which IMGs originate.

This study sheds important light on the issue of recruiting IMGs in the UK. However, it is not without limitations. First, its use of surveys makes it prone to many of the pitfalls associated with the use of this method in data collection (24). Second, and relatedly, the participants of the study were in one NHS board, making it difficult to confidently obtain generalised conclusions.

Conclusion

In view of recent efforts to critically investigate the state of the NHS, including the Darzi report, the insights and recommendations provided by the participants of this study are particularly relevant.

We believe that there are unnecessary bureaucratic barriers facing IMGs entry into the UK medical job market. With these barriers continuing to exist, the shortage of human resources for health in the UK is likely to continue if not get worse. Therefore, we recommend several policy reforms to overcome these barriers. First, the UK should perhaps consider relaxing its stringent language, visa and medical exam requirements. Second, it should adopt fairness in its approach to recognising medical expertise and skills obtained overseas. Third, it should formalise clinical attachments programmes and offer opportunities for meaningful introductions to the NHS through allowing genuine patient encounters. Finally, digital innovations and social media tools should be utilised to facilitate knowledge exchange and training amongst IMGs in knowledge and skills that are of use to modern day medical practice in the UK.

We recognise that these recommendations might increase the attractiveness of the UK to IMGs from Low- and Middle-Income countries. Such recruitment would worsen shortages of human resources in the latter countries. However, our recommendations are specific to those IMGs who are already in the UK. Furthermore, we strongly advocate the adherence to WHO’s ‘Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel’ (25).

References

- WHO. WHO report on global health worker mobility [Internet]. Who. 2023. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/370938/9789240066649-eng.pdf?sequence=1

- Agyeman-Manu K, Ghebreyesus TA, Maait M, Rafila A, Tom L, Lima NT, et al. Prioritising the health and care workforce shortage: protect, invest, together. Lancet Glob Heal [Internet]. 2023 Aug;11(8):e1162–4. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214109X23002243

- OECD Data Explorer [Internet]. 2024. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/datasets/oecd-DE.html

- BMA. NHS medical staffing data analysis [Internet]. 2024. Available from: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/nhs-delivery-and-workforce/workforce/nhs-medical-staffing-data-analysis

- Royal College of Physicians. Snapshot of UK consultant physicians 2023 [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://www.rcp.ac.uk/improving-care/resources/snapshot-of-uk-consultant-physicians-2023/

- Medical Schools Council. The expansion of medical student numbers in the United Kingdom, Medical Schools Council Position Paper. 2021;(October):1–23.

- Matthias Wismar, Claudia B. Maier, Irene A. Glinos, Gilles Dussault JF. Health professional mobility and Health systems. Eur Obs Heal Syst Policies [Internet]. 2011;1–632. Available from: http://www.sfes.info/IMG/pdf/Health_professional_mobility_and_Health_systems.pdf

- Council GM. The state of medical education and practice in the UK Workforce report 2023. 2023.

- Al‐Haddad M, Jamieson S, Germeni E. International medical graduates’ experiences before and after migration: A meta‐ethnography of qualitative studies. Med Educ [Internet]. 2022 May 5;56(5):504–15. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/medu.14708

- Hashim A. Educational challenges faced by international medical graduates in the UK. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017;8:441–5.

- Kalra G, Bhugra DK, Shah N. Identifying and Addressing Stresses in International Medical Graduates. Acad Psychiatry [Internet]. 2012 Jul 1;36(4):323. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1176/appi.ap.11040085

- Wakeford R. International medical graduates’ relative under-performance in the MRCGP AKT and CSA examinations. Educ Prim Care [Internet]. 2012 May 7;23(3):148–52. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14739879.2012.11494097

- Ghosh M, Chatterjee S. Aspirations of unemployed international medical graduates in the UK. Sushruta J Heal Policy Opin [Internet]. 2021 May 1;14(2):1–8. Available from: https://sushrutajnl.net/index.php/sushruta/article/view/119

- Efe SS. A New Model for Economic Integration of ‘Refugee Doctors’ in the UK: Opportunities and Costs of New Policy Initiatives. Migr Divers [Internet]. 2023 Feb 28;2(1):1–20. Available from: https://journals.tplondon.com/md/article/view/2933

- Fernández-Reino M, Brindle B. Migrants in the UK Labour Market: An Overview [Internet]. 2024. Available from: https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/migrants-in-the-uk-labour-market-an-overview/

- Hudson N, Runge J. Recruitment of workers into low-paid occupations and industries: an evidence review. Equality and Human Rights Commission; 2020.

- Wood M, Hales J, Purdon S, Sejersen T, Hayllar O. A test for racial discrimination in recruitment practice in British cities [Internet]. 2009. Available from: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.bollettinoadapt.it/old/files/document/3626ATESTFORRACIALDI.pdf

- Coghlan D, Fagan H, Munck R, O’brien A, Warner R. International Students and Professionals in Ireland: An Analysis of Access to Higher Education and Recognition of Professional Qualifications [Internet]. 2005. 1–39 p. Available from: www.integratingireland.ie

- Rajpara M, Chand P, Majumder P. Role of clinical attachments in psychiatry for international medical graduates to enhance recruitment and retention in the NHS. BJPsych Bull [Internet]. 2024 Jun 7;48(3):198–204. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S2056469423000591/type/journal_article

- Berlin A, Cheeroth S, Agell I, Siddiqi S. Clinical attachments for overseas doctors. BMJ [Internet]. 2002 Nov 16;325(7373):160S – 160. Available from: http://www.bmj.com/cgi/doi/10.1136/bmj.325.7373.S160

- BMA. Clinical attachments [Internet]. 2024. Available from: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/international-doctors/getting-a-job-in-the-uk/clinical-attachments

- Taylor M. Why is there a shortage of doctors in the UK? Bull R Coll Surg Engl [Internet]. 2020 Mar;102(3):78–81. Available from: https://publishing.rcseng.ac.uk/doi/10.1308/rcsbull.2020.78

- Thornton J. Visa bureaucracy causing GPs to leave the UK. Lancet [Internet]. 2022 Jul;400(10346):88. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673622012703

- Andrade C. The Limitations of Online Surveys. Indian J Psychol Med [Internet]. 2020 Nov 13;42(6):575–6. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0253717620957496

- Health Workforce (HWF). WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2010. p. 8. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/wha68.32