IN A NUTSHELL

Editor's note

With 38 years of international education and development experience, Clare Hanbury has collaborated with esteemed organizations including DANIDA, UNICEF, UNESCO, Save the Children, and the UBS Optimus Foundation. Her career began in the classroom, teaching in Kenya and Hong Kong, and evolved into leading impactful programs that promote children’s active participation in their health and education.

On 13th July, 2013 She founded Children for Health - CFH to deliver essential health information directly to children, enabling them to share knowledge within their families, schools, and communities.

Her passion lies in creating practical tools and innovative strategies that make health education accessible, engaging, and transformative, ensuring that children become active agents in building healthier, more resilient communities.

In this connection, PEAH had the pleasure to interview Clare Hanbury relevant to her experience and strategy implementation to secure and enhance Children for Health success

With 38 years of international education and development experience, Clare Hanbury has collaborated with esteemed organizations including DANIDA, UNICEF, UNESCO, Save the Children, and the UBS Optimus Foundation. Her career began in the classroom, teaching in Kenya and Hong Kong, and evolved into leading impactful programs that promote children’s active participation in their health and education.

On 13th July, 2013 She founded Children for Health - CFH to deliver essential health information directly to children, enabling them to share knowledge within their families, schools, and communities.

Her passion lies in creating practical tools and innovative strategies that make health education accessible, engaging, and transformative, ensuring that children become active agents in building healthier, more resilient communities.

In this connection, PEAH had the pleasure to interview Clare Hanbury relevant to her experience and strategy implementation to secure and enhance Children for Health success

By Daniele Dionisio

PEAH – Policies for Equitable Access to Health

INTERVIEW

Clare Hanbury

CEO and Founder, Children for Health – CFH

–PEAH: Clare, as CFH website makes it clear, many hundreds of thousands of children die each year because their parents and others lack basic health information and skills. At the same time, millions of older children throughout the world play a key role in caring for younger ones.

On this matter, informing, recognising and praising older children helps improve this care. They can, indeed, learn, collect and share basic health ideas and skills to keep healthy themselves, and help others.

In this connection, what about the Mission of Children for Health?

–Hanbury: Our mission at Children for Health is to provide young adolescents (9-14), either directly or indirectly – with simple, memorable, shareable health education messages, stories and activities that connect new knowledge, skills and attitudes with their real lives. We aim to mobilise children as health activists among their friends, in their families and in their communities. Sharing knowledge, saving lives! That’s our work.

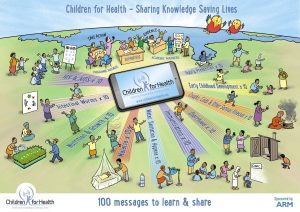

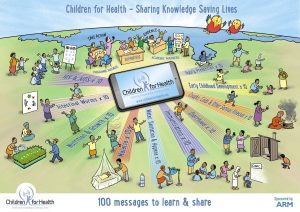

–PEAH: As written, “At Children for Health it is our dream that, before children leave primary school, every child will have learnt and shared 100 important health messages.” Please, let us know in depth about these messages

–Hanbury: The 100 Health Messages for Children to Learn & Share are simple, reliable health education messages aimed at children aged 9-14. We feel that it is especially useful and important to make sure that young adolescents aged 9-14 are informed because this age group are often caring for young children in their families. Also, it’s important to recognise and praise the work they are doing to help their families in this way.

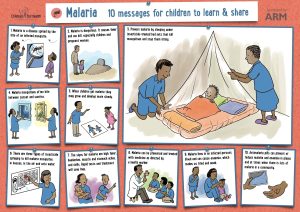

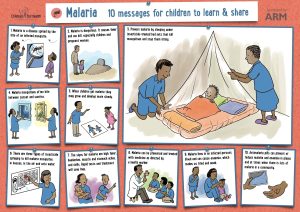

The 100 messages comprise 10 messages in each of 10 key health topics: Malaria, Diarrhoea, Nutrition, Coughs Colds & Illness, Intestinal Worms, Water & Sanitation, Immunisation, HIV & Aids and Accidents, Injury and Early Childhood Development. The simple health messages are for parents and health educators to use with children at home, in schools, in clubs and in clinics.

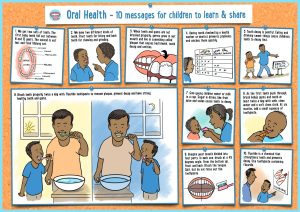

All our health messages have been developed and reviewed by health educators and medical experts. They can be translated and adapted provided that the health message remains correct. Great care has been taken to ensure that the health messages are accurate and updated and now most of our ten sets of ten messages have been visualised and can be downloaded as full colour posters from our website! I say ‘most’ as we are just completing the series, and we should have ten posters with ten messages on each – completed by July 2025. This is a real achievement as it takes ages to go through our process! And to find funding of course!

Health educators use these health messages to structure health education activities in their classrooms and projects, and to stimulate discussions and other activities.

We want all children to learn and share 100 health messages – 10 messages in 10 topics – before they leave primary school. Just like they learn their times tables…These could be our carefully created messages OR adapted versions for different countries and communities

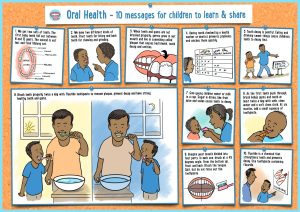

–PEAH: Knowing that literacy levels in many parts of the world are low, Children for Health has developed a series of posters for health that provide the visual starting point for fruitful discussions on health issues and disease and the role that children can play in their prevention and treatment. Below are some examples including one that illustrates Children for Health’s 100 messages, as well as posters for Oral Health, Malaria.

https://www.childrenforhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/CfH_Poster.pdf

Can you, please, add information on that?

–Hanbury: The idea to visualise our health messages didn’t start with us — it came from the teachers and health workers themselves. They asked us to turn the messages into pictures so that children (and adults!) could understand them easily.

We began by creating a poster on malaria. The response was incredible. As soon as people saw the images, they immediately got what Children for Health is all about — and how powerful children’s participation can be.

From that day on, we knew that visual storytelling was key to making our work clearer, stronger, and more inspiring.

–PEAH: How does CHF work in a scalable way while empowering children to become agents of change through free-of-charge health education materials for them and their educators?

–Hanbury: We’re already scaling in two key ways:

Through Our Health Education Materials

- Our co-created materials are downloaded globally every month and used in training courses, school curricula, and health clinics.

- Some organizations adapt our messages for videos in clinics, calendars, or as core content when developing new health resources (e.g., HIV education for children).

- Our materials act as a shortcut for educators and health workers, helping them quickly develop effective tools.

Through Partnerships & Government Programs

- We work directly with projects, like one in Mozambique, where we helped integrate our nutrition approach into the school curriculum—alongside teachers and children.

- Involving children in these processes shows adults how capable they are, often challenging underestimations about their role in health education.

- By partnering with government programs, our approach reaches more schools and communities, ensuring sustainability and long-term impact.

By combining these approaches, we’re making sure our work continues to scale and reach more children worldwide.

–PEAH: What through is CHF funded?

–Hanbury: Funding, like for many organisations, is challenging and always ongoing. Our work is primarily supported in two key ways: through programmatic partnerships and content creation.

Programmatic Partnerships

We are employed as curriculum designers, trainers, mentors and advisors by existing programmes and invited to bring our approaches, materials, and expertise to strengthen those initiatives. Our role varies based on the needs of the programme and can include:

- Programme Design: Helping organisations develop health education programmes from the ground up.

- Children’s Participation Integration: Assisting in embedding meaningful children’s participation within existing programmes.

- Training and Capacity Building: Conducting training sessions, including training of trainers.

- Monitoring & Evaluation: Designing indicators and frameworks to assess programme impact.

This programmatic work is typically funded by the entity financing the broader programme, with our services integrated into the overall structure.

Content Creation

We also develop educational materials, sometimes as part of a programme or in response to pressing health issues. Some of our content creation approaches include:

- Programme-Linked Content: For example, in Eswatini, we are helping schools develop anti-bullying messages, safe school surveys, and related content. While our work is funded within this specific programme, the content produced is made more widely available for general use.

- Response to Emerging Health Priorities: During major health crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic or Ebola outbreaks, we were employed to create educational materials, including storybooks, posters, and teacher’s guides.

Given the broad range of topics we address, our funding landscape is diverse and requires continuous engagement with donors, partners, and stakeholders to sustain and expand our work.

–PEAH: Children for Health collaborates with other organisations and programmes to build capacity, offer technical advice, mentoring and training, and create teaching materials and programme strategy. In this respect, how many partners does CHF currently engage with?

–Hanbury: We focus on working with partners who share our mission and values, ensuring that our expertise in children’s participation in health education is used effectively and is sustainable. By collaborating closely with a few partners at a time, we provide tailored support, co-create impactful materials, and help sustain long-term initiatives. Rather than leading projects, we aim to support others in achieving their goals.

Our current Partnerships are with organisations in:

- Eswatini – Supporting schools with anti-bullying messages, safe school strategies, and resources on sexual harassment prevention. Our work started two years ago – with an HIV/AIDS poster and storybook.

- Kenya – Integrating health education into school water and sanitation curricula and community outreach programs.

- Pakistan – Partnering with a large organization to adapt our Type 2 Diabetes materials, originally developed with partners in Guam.

Also, we are currently finalizing the last two posters in our 10-poster series and working with new partners to review and refine them.

Even this does not really reflect the true picture as each day I’d probably spend some time engaging with those that contact us looking for resources, support, tips and mentoring. I would not call these ‘partnerships’ but some of these types of lightweight contact then turned into important alliances and strong partnerships.

We welcome collaborations on key health topics such as nutrition, disease prevention, mental health, and life skills—ensuring children are active participants in their own well-being. We are grateful to our partners and networks for their support and look forward to growing our impact.

–PEAH: Children for Health is dedicated to getting valuable information to the people who need it most. Relevantly, is its content being translated into languages other than English? If so, how many so far?

–Hanbury: On our website, you can find our original draft of 100 health messages in 23 languages, made possible by a generous donation years ago. However, managing translations is a significant challenge, and we can only update them when funding allows. Since health messages evolve over time, we include a note in each booklet directing users to our website for the latest English version.

We do maintain some resources more closely. In Portuguese, we have four storybooks, a nutrition guide, and two posters developed in Mozambique. Other translations have come from generous volunteers and specific partnerships. For example:

- Lesotho – A special glasses storybook in Sesotho (co-created with children).

- DRC – A diarrhoea poster in French (developed with local colleagues working with save the children).

While we do our best to support translations, those needing up-to-date materials in other languages should find their own translators and ideally inform us. We’re always happy to promote translated materials, though we can’t guarantee accuracy. It’s inspiring to see people adapting our work to reach more communities!

–PEAH: What about the CHF Team?

–Hanbury: Children for Health operates with a dedicated but small team. We have four active trustees with diverse expertise, a website manager, and a network of authors we call upon when needed. Our artist has been with us from the start, a collaboration that began during my time at The Child-to-Child Trust before launching Children for Health.

We also rely on a social media expert and volunteers, along with occasional administrative support. As the almost full-time CEO, I work remotely, and so do our team members. In fact, our “headquarters” is essentially a laptop, as we’re often travelling.

But the true heart of Children for Health lies in those who use our materials—teachers, health workers, programme managers, and headteachers—who bring our work to life in schools and communities worldwide. Their dedication and impact make them an essential part of our extended team.

–PEAH: What results have been achieved and how many children and parents have been involved in your activism so far?

–Hanbury: Tracking the impact of Children for Health is challenging. Since 2022, our materials have been downloaded 150,000 times in over 158 countries. However, it is difficult to determine how many teachers, parents, and children have actively used them. Some may explore our resources out of curiosity, while others integrate them into training programs that then reach hundreds of teachers and thousands of children.

For structured programs, tracking growth is more straightforward—for example, we know that in one programme it was expanded from 12 to 15 to 32 schools. Considering that each school serves between 300 and 600 children, and those children share knowledge with their families and communities, our reach is potentially in the thousands per school.

As a small organisation, conducting large-scale research is challenging, but we receive ongoing anecdotal feedback from users who find our materials valuable. Our impact has also been recognised through two awards: the Global Impact Award and the Small Charity Big Achiever Award, where our work was thoroughly assessed.

While quantifying our exact influence is complex, we remain committed to empowering children as health messengers worldwide.

–PEAH: Thank you Hanbury for the excellent work joining humanitarian and entrepreneurial commitment.