Despite the relevant Chinese commitment in Africa, concern still remains about the actual Chinese efforts, but also about the effectiveness of the Chinese agricultural projects in Africa. These weak points are strengthened by the fact that regional stakeholders often complain about the lack of coordination and governance of the projects financed by China all over Africa. In addition, even if investment in agriculture seems to be intended to solve Africa's hunger issues, many still view China as engaged in a self-interested, exploitative grab for resources to feed its fast-paced growth

by Pietro Dionisio

Degree in Political Science, International Relations

Cesare Alfieri School, University of Florence, Italy

China-Africa Agricultural Cooperation: for the Sake of Whom?

Since the 1960s China has been tangibly present in Africa. This is proved by the fact that the Chinese authorities have implemented approximately 220 agricultural aid projects including several sectors, such as farming, animal husbandry and fishery and farmland water conservation.

This involvement in African agricultural affairs improved considerably after the Forum on Africa and China Cooperation Beijing summit in November 2006[1], that showed the commitments to the agricultural sector and the diversity of Chinese investments in Africa. According to this summit, in accordance with its African partners China agreed to build 14 agricultural centers in 33 countries, to send 100 senior agricultural experts and to train 15000 talents in various fields (1500 of them were to be agricultural technology professionals).

This major Chinese involvement in Africa is in accordance with a general view of the Central government. In fact, the former premier Wen Jiabao announced additional steps to reach UN Millennium Development Goals[2]. He maintained that it was necessary to intensify efforts to provide foreign countries with more agricultural aid [3].

China has become one of the principal players through several agreements signed with various African countries. For instance, the Government invested US$ 800 million in Mozambique to modernize agricultural infrastructure. This modernization should be achieved through the dispatch of 100 Chinese agricultural experts working in several research stations within the country. The duty of these experts is to work in collaboration with local groups to improve field yields and find other ways to increase the overall performance in the agricultural sector.

Despite the relevant Chinese commitment in Africa, concern still remains about the actual Chinese efforts, but also about the effectiveness of the Chinese agricultural projects in Africa. These weak points are strengthened by the fact that regional stakeholders often complain about the lack of coordination and governance of the projects financed by China all over Africa.

In addition, even if investment in agriculture seems to be intended to solve Africa’s hunger issues, many still view China as engaged in a self-interested, exploitative grab for resources to feed its fast-paced growth[4].

Historical Perspective

Especially in the last decade China has strongly increased its presence in African agriculture. Despite this constant presence on the African ground, it is still not clear to what extent the Chinese engagement has produced results in terms of agricultural development in African countries.

In this respect, information on investment and data on actual activities are very difficult to be obtained.

China could play an important role in Africa thanks to its previous experience. In fact, the challenge for food security holds lessons in several areas such as the application of technology and mechanization on agriculture, the improvement of social protection and agricultural and rural development.

China has always made clear that agriculture plays a key role in its aid programs for Africa. However, current discussions between China and African authorities have not produced considerable results due to many reasons. In fact, two main problems are at issue. First of all the presence of a mutual suspicion on both sides. Secondly, China’s preference to directly consult private entrepreneurs instead of a jointly coordinated partnership with regional bodies, such as CAADP[5], is another obstacle in the relations with African authorities[6].

The Chinese involvement dates back to the 1950s. The Bandung Conference of Non-Aligned Nations in 1955 can be considered as the beginning of the Chinese interests towards Africa[7].

At that time China was looking for new partners in Africa so as to become the third pole, thereby counterbalancing the Soviet Union’s hegemony and the Western “imperialism”.

The first event that can be cited as the beginning of the agricultural cooperation between China and African countries is the grant of food aid to Guinea in 1959. After that, China undertook several other agricultural projects on the continent[8].

The history of the Chinese agricultural involvement in Africa can be divided into three main phases:

“Non Reimbursable Assistance” (1959-1969): this period was characterized by Chinese unilateral assistance and by the support to national liberation movements of African countries.

China’s agricultural assistance was intended as a tool in order to support the consolidation of political independence of the African countries linked with the aim of developing diplomatic relations between China and African countries.

In this period the efforts made were focused on the construction of agricultural technology, experimental stations, promotional stations, large farms and water conservancy facilities.

At the beginning, the projects had a positive impact, but soon after the handover to national governments, they began to deteriorate. This was the consequence of lack of financial inputs and inadequate management experience[9].

“Cooperation Based on Mutual Benefit” (1970-1999): during the 1970s, due to the implementation of the “open-up policy” and the weakening of ideological factors, the Chinese-African relationships no more experienced a unilateral non reimbursable cooperation, but a bilateral beneficial one linked with a gradual introduction of multilateral cooperation.

The principal tools used were technology sharing, talents output and personnel training[10].

In this phase, enterprises became the main bodies to implement plans for assistance. By the late 1970s, several Chinese firms invested in the development of new agricultural projects using funds from China’s foreign aid and preferential loans[11].

“Comprehensive Development” (2000-to date): the rapid economic development of the Chinese economy marks a new impulse in the Chinese-African cooperation. The establishment of the Forum on Chinese-African Cooperation (FOCAC) is an important step in this direction.

This partnership focuses on improving the independent development of agriculture in Africa through a set of comprehensive measures.

In order to favor these plans, China uses several funds including funds for foreign aid and from international organizations, and State funds for Africa.

These comprehensive plans include several projects concerning technology information sharing, the launch of pilot centers for agricultural technologies and the dispatching of agricultural experts with the aim of launching vocational education in agriculture or technological training. This approach is confirmed by China’s African policy as published in 2006:

“Focus will be laid on the cooperation in land development, agricultural plantation, breeding technologies, food security, agricultural machinery and the processing of agricultural and side-line products. China will intensify cooperation in agricultural technology, organize training courses of practical agricultural technologies, carry out experimental and demonstrative agricultural technology projects in Africa and speed up the formulation of China–Africa Agricultural Cooperation Program.”[12]

Agricultural engagement in Africa is defined as “South-south” cooperation[13]. This definition underlines the idea of a reciprocal partnership with mutual benefits. This policy continues to increase political relationships and soft power, developing commercial opportunities for national enterprises and enhancing China’s resource security[14].

For the period from 2012 to 2015, several measures have been established under the China-Africa cooperation:

- To support CAADP (Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program) for a ‘growth-oriented’ agricultural agenda for Africa

- To send teams to train African agricultural technicians

- To support agricultural vocational education system and send teachers

- To build more agriculture demonstration centres

- To provide technical support for grain planting, storage, processing and circulation

- To encourage Chinese financial institutions to support corporate cooperation in planting, processing, animal husbandry, fisheries and aquaculture

- To support UNFAO ‘Special Program for Food Security’

- To facilitate access for African agricultural products to the Chinese market

- US$20 billion credit line for infrastructure, agriculture, manufacturing and African SMEs

- To publish and translate agricultural technology materials; joint participation in book fairs in China and Africa[15].

Tools Employed

Several actors play a role in this partnership, the main one being the Chinese Ministry of Commerce backed by the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Science and Technology. Altogether, these institutions coordinate agricultural programs.

The patronized plans are implemented afterwards by Chinese institutes, state-owned enterprises and private firms through a competitive bidding process.

The China Development Bank and the Export Import Bank of China are tasked with financing these projects in the form of development commercial finance or export credits.

In 2006, the China-Africa Development Fund was established with the aim of enhancing Chinese-African commercial ties. It is noteworthy that this fund signed an agreement with the China State Farm Agribusiness Corporation in order to establish joint company financing agricultural investment[16].

The Forum on China Africa Cooperation was implemented in 2000. Meetings are held every three years, allowing discussions among partners about projects and future engagements. Moreover, an increasing number of Chinese NGOs is committed in the implementation of agricultural plans in Africa.

It is not easy to estimate the amount of aid provided. In fact, the Chinese authorities are often more interested in emphasizing the impact on the ground of their action than the loans given[17].

Agricultural aid is mainly provided only to those countries that recognize the “One China Policy”[18], and particularly in two forms: either monetary aid or in kind payment. These loans are designed to support food production, breeding, storage and transport and infrastructure development. Furthermore, aids are given in terms of agricultural equipment, trainings, technical assistance and scholarships[19].

Chinese investment is another increasing factor. Several actors, including state owned enterprises, have a role in this sector, which makes it difficult to figure out the concrete management of the system. According to Scissors and in spite of what we might think, it seems that China is not engaged in large-scale African farming for export. In fact, to our knowledge China seems to have only 54 overseas projects covering 4,9 million hectares of land, of which only 463,792 hectares are in Africa[20].

Chinese Agricultural Investments in Africa

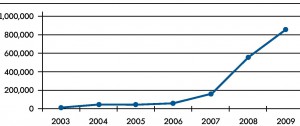

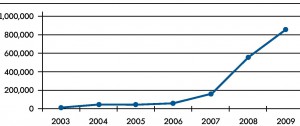

Figure 1: China’s outward FDI stocks in Africa ($10,000), 2003–09

Source: MCC, 2009 Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment. MCC, National Bureau of Statistics of China & State Administration of Foreign Exchange of China, Beijing, 2010

China has strongly increased its Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) in Africa since the third Ministerial Conference of FOCAC in 2006[21]. This increasing volume of direct investments has not been interrupted. In fact, it grew from US$ 30 million in 2009 to US$ 82,4 million in 2012.

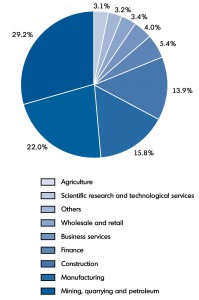

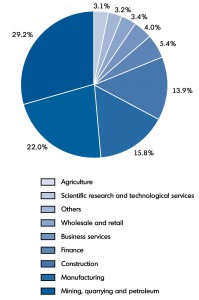

Despite the fact that the share of Chinese agricultural investment is only 3,1% of the total investment in Africa, this amount is expected to increase considerably in the near future because agricultural cooperation is becoming a priority not only in China but even in some African countries.

Figure 2: China’s outward cumulative FDI stocks in Africa by industry (%), 2009

Source: Helen Lei Sun, “Understanding China's agricultural investments in Africa", 2009

According to the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) n.1 that establishes the eradication of extreme poverty and hunger, the Chinese authorities have supported agricultural investment in Africa, since they consider it as a necessary tool to achieve the MDG n.1[22].

Having laid emphasis on agriculture as an effective tool to reduce poverty, China is focusing its efforts mainly on rural infrastructure.

In fact, the productivity of the African land is usually low due to poor water irrigation systems and water resources. It is noteworthy that in Sub-Saharan Africa less than 4% of renewable water resources are used for agriculture. There are several barriers that have limited the efficiency of agriculture in Africa. These include lack of financial and human resources, poor performance of rural infrastructure and agricultural technology and an inadequate market access.

China has been extremely active in this sector. It has provided several countries, such as Zambia and Nigeria, with loans and implemented over 500 agricultural infrastructure projects[23].

The case of Zambia is relevant. To enhance the country’s storage capacity and consequently food security, the Chinese authorities signed an agreement with the Zambian government for the construction of twelve major grain storage facilities, covering a total area of 30 000 square meters equal to a storage capacity of 100 000 tons.

The Zambian example is just one among many. In fact, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce has signed agreements with 35 African countries for the building of large-scale infrastructure. The bulk of the investment (almost the 70%) is in Nigeria, Angola, Sudan and Ethiopia, but other projects concern Congo, Mali, Mozambique and Tanzania[24].

Moreover, several Chinese professionals, as already mentioned, are dispatched in Africa to build agricultural demonstration bases. Training courses are organized on issues such as rice and vegetable cultivation , meat processing and correct use of agricultural machinery.

Cameroon, Ethiopia, Benin, Liberia, Mozambique, Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda were the first countries in which China began to establish agricultural technology demonstration centers in 2009. In these centers, Chinese experts have to share their knowledge with local people thereby strengthening the African agricultural development. In this respect, 11 rice demonstration areas were established in Guinea-Bissau covering an area equal to 2 000 hectares. The results were really remarkable. For the majority of the products planted the output increased over three times encouraging the expansion of the covered area to 3 500 hectares[25]. Moreover, in this country China State Farm and Agribusiness Corporation collaborated with the China Hybrid Rice Engineering Research Center to introduce high-yielding hybrid rice.

It is noteworthy that the investment of Chinese firms in agriculture has considerably increased grain supplies in Africa, improving the domestic agricultural productivity of those countries included in the agreements.

Several situations can be cited. For instance, in Mozambique, Chinese investment has supported the establishment of 300 hectares of experimental paddy fields. Thanks to the efforts of the Chinese rice experts dispatched there, local farmers have the possibility to increase their yields per hectare by about two tons more than the previous yields. In addition, Chinese firms have invested in the improvement of local farmland, water conservancy systems and agricultural production conditions.

Rwanda is another case in which Chinese efforts have produced some good results. The Rwandan government has signed an agreement for a farmland improvement project aiming at increasing the utilization of water resources. The loans provided come from the African Development Bank and from Chinese enterprises[26]. In Ghana, too, there is a strong presence of Chinese investment. Here the efforts are mainly focused on the development of agricultural infrastructure[27].

Table 1: Chinese-aided agricultural technology demonstration centers in Africa

| Country |

Implementing Organization |

Main demonstration Field |

| Benin Republic |

China National Agricultural Development Group |

Corn & Vegetables |

| Cameroon |

Shaanxi Land-reclamation, Agriculture & Industry and Commerce corporation |

Rice |

| Congo (Brazzaville) |

Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences |

Cassava |

| Ethiopia |

Guangxi Bagui Agricultural Science & Technology Co.,Ltd. |

Cash Crops |

| Liberia |

Yuan Longping High-tech Agriculture Co.,Ltd |

Rice |

| Madagascar |

Hunan Academy of Agricultural Sciences |

Rice |

| Mozambique |

Lianfeng Agricultural Development Corporation |

Seed breeding & Livestock |

| Rwanda |

Fujian Agriculture & Forestry University |

Paddy and Silkworm |

| Sudan |

Academy of Agricultural Science |

Corn and Wheat |

| South Africa |

China National Agricultural Development Group |

Aquaculture |

| Tanzania |

Agricultural Tech Company |

Rice |

| Togo |

Huanchang Infrastructure Construction Company |

Rice |

| Uganda |

Huaqiao Fenghuang Group |

Aquaculture |

| Zambia |

Jilin Grain Group |

Corn and Wheat |

| Zimbabwe |

Research Institute of China agricultural Mechanization |

Agricultural machinery & Irrigation |

Source: Rex Ukaejiofo, “China-Africa agricultural co-operation Mutual benefits or self-interest?”, 2014

However, according to a recent study of AFD-CIRAD[28], it seems that some of the 100 Chinese projects are awarded as grants and the rest as private or public loans covering a small number of countries, namely Benin, Mali, Senegal, Ghana, Zimbabwe, Tanzania and Mozambique[29].

Special Program for Food Security

The Special program for Food Security is an important initiative started in 1994. The goal of this plan is to help low-income countries face food deficit and increase food security. In addition, a second aim is the promotion of the global south alliance in addressing food security. An important element of the plan is the establishment of partnerships through which the member countries should share their experience and knowledge in order to address the food issue also in other contexts.

Since 1996 the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture has managed to sign an agreement with FAO and countries in the global south in order to find a solution for some important issues such as agriculture and food security.

As a result, until now China has dispatched more than 700 agricultural experts mainly to seven countries: Nigeria, Ethiopia, Sierra Leone, Gabon, Mali, Mauritania and Ghana.

According to this program, China committed itself to donate US$ 30 million for the establishment of a trust fund aimed at boosting agricultural production capacity and increasing export and assistance for such countries in Africa.

The program focuses on important issues such as agricultural economy, agricultural planning, agricultural management, crop cultivation, animal husbandry and veterinary, aquaculture, processing of agricultural goods, agricultural machinery and agricultural engineering. Chinese firms have mainly invested in such fields as breeding of improved seeds, grain and cash crop planting, and processing of agricultural products[30].

Important investment was made in Nigeria where, starting from 2004, almost 500 experts and technicians were dispatched. In this country, together with local partners, experts implemented comprehensive techniques such as China’s swine methane-fruit tree ecological agricultural model and the raising of ducks in paddy fields. Moreover, new productive methods were experimented, ranging from a strong rice seedling on upland fields to a reasonable compact planting, regulation and control of moisture and fertilizers through production.

All these experiments and demonstrations were collected in a book, “Booklet on Practical Technologies for China-Nigeria’’, that gained a considerable importance because it became a guideline book for agricultural production not only in Nigeria, but also in other African countries[31].

Sierra Leone is another country which benefits from Chinese investment. Here four country stations were implemented in Kono, Kabala, Moyamba and Makali. In each of these stations a different technology is used. These technological devices include bio-gas digestion, honey bee culture, fish ponds and small scale agricultural mechanization. Moreover, teaching basic skills in rice, vegetable and poultry production is considered another key element of the country project.

Due to language difficulties, experts used different teaching methods. In fact, the “teaching by doing” method, based on practical demonstrations, was quite often applied in order to share practical skills. Moreover, each of the four stations implemented concrete demonstration of high yields.

The team dispatched there also performed some consolidation work: for example, the rebuilding of the irrigation system at Makali farm, a project built through Chinese investment in the 1970s[32].

Chinese Engagement in Mozambique

Chinese engagement in Mozambique began immediately after the independence of this country in 1975. In fact, in that year 120 Chinese agricultural experts were dispatched from the province of Sichuan. The aim was to help Mozambique develop 230 hectares of the Moamba state farm and the Matama farm in the Niassa province.

The partnership was strengthened in the mid 1980s when China decided to send farm machinery and an agricultural team to provide aid for the implementation of the “Green Zone program” in Maputo’s urban area[33]

In the same period, Chinese firms began to invest in the country and it was only after the end of the Mozambican civil war in 1992, that the two countries started to talk about the possibility of establishing joint venture. Things went slowly. By 2000 Mozambique received only one investment from China, coming from Anshan Grain and Oil Export Import Company, that invested in 20 hectares near Maputo and US$ 500 000 in the Zhongan vegetable farm[34].

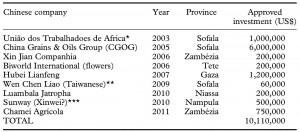

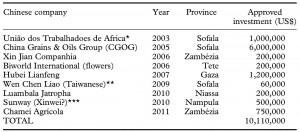

Despite this slow beginning, the partnership went on and, between 2000 and 2011, nine additional enterprises invested in the country.

Two of these nine projects are particularly worth mentioning. The first one was a proposal by China Grains and Oils Group Corporation to invest US$ 6 million. The second one regarded Hubei Liangfeng, a provincial firm, that would invest US$ 1,5 million in the country.

Moreover, the Chinese authorities decided to finance the establishment of an agro-technology demonstration center that was to be built between 2006 and 2012.

In 2005 a joint venture between Mozambican businessman Zaidi Ali and China Grains and Oils Group was established for the implementation of a big project aimed at the production and processing of soybeans in Sofala province. Despite the efforts, the project failed. Unfortunately, there was evidence that the field was not appropriate for this commodity. Additionally, machinery imported from China was not suitable for the conditions of Mozambique and the venture could not secure work for the Chinese dispatched technicians[35].

Table 2: Chinese planned and approved agricultural investment in Mozambique (2000–11)

Source: Brautigam D., Ekman SM., "Briefing rumours and realities of Chinese agricultural engagement in Mozambique" (2012)

In 2004 another relevant plan was launched. This project was part of the Chinese “friendship farm” plans. The term friendship pinpoints a plan requested by the hosting country and considered politically important for its authorities. In 2004 the Mozambican government asked its Chinese counterpart to help develop its rice sector. After having studied the feasibility of the plan, China agreed to build a demonstration farm in the Gaza province. The Chinese firm Hubei State Farm Agribusiness Corporation accepted to invest US$ 1,2 million in the project[36]. The plan was based on two main purposes. Firstly, part of the Chinese political task was to solve Mozambique’s food limitations focusing on improving grain and vegetable yields. But the venture made experiments also for other products, such as soybean, tobacco, rapeseed and organic vegetables, in order to sell them in the European and Chinese markets.

At the beginning the farm was quite small. It consisted only of 100 hectares devoted to rice production. In 2008 a joint venture was formed with a Chinese private enterprise, the Xiangyang Wanbao Group, which helped boost the production of soybeans, vegetables and other cash crops. By December 2011 the planted land reached 200 hectares and Chinese experts and workers were employed to build, develop and maintain the irrigation systems.

It is noteworthy that this plan was implemented with the contribution of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation that decided to finance it and use it as a test for the Gates Foundation’s “Green Super Rice” program[37].

In 2011 the Chinese firms increased their presence in the country. Just to make an example, the Shandong Xinwei Grain and Oil Food Corporation launched Xinwei International Mozambique Co. Ltd. in Nampula. The company employed 130 Mozambicans and mechanized cultivation of 140 hectares of land. The main commodities planted were maize, groundnuts, sesame and mung beans. Moreover, a Chinese cotton company set up operations in Mozambique (and Malawi), buying cotton from contract farmers and processing the cotton locally[38].

Even though China is continuing its investment in Mozambique, its efforts are not easily applicable. In fact, Chinese companies investing in the country face several obstacles in accessing lands, because investors have to consult with local communities and obtain their acceptance, before lodging formal application with the authorities in charge. Nevertheless, it is not easy to negotiate with local communities due to the arising land identification problems. Moreover, especially in some contexts, it is difficult even to identify the legitimate authority representing the tribal communities occupying those lands. For example, definitely due to these issues, China-Africa Cotton Mozambique[39] adopted a new method. In fact, through this model, China-Africa Cotton Mozambique provides training and inputs to local peasants and, in return, purchases raw cotton from them. Working this way, it can strongly reduce costs associated with accessing land[40].

Another relevant problem that Chinese investors have to face is the poor condition of infrastructure, especially poor transportation and damaged irrigation systems, that often impede the implementation of activities such as expanding production or the adoption of new technology.

In Mozambique many problems are caused by a poor information system for the investors. In fact, the State is unable to provide correct information about lands in order to ensure the success of investment operations. In 1997 the National Land Cadastre was established in order to improve the situation. Theoretically, the aim of this institution is the collection of information about different types of occupation and land uses, soil fertility, hydraulic reserves and mining exploration zones. In addition, it should organize the use of land, its protection and conservation. In practice, the institution neither can collect information to guide agricultural investors, nor achieve the above tasks[41].

This lack of information produced the failure of the above mentioned China Grains and Oils Group in the Sofala province. Operations failed due to poor planning. In fact, the company did not get correct information about the type of soil. As a consequence, it brought seedling and machinery from China that were not suitable for that field, which caused the company to give up the project.

Chinese investment in Mozambique is still insignificant if compared to other forms of investment related to natural extractive resources. In fact, agriculture accounts only for 1% of China’s FDI to the country and only 12% of the Mozambican export goes to China (data of 2008).

Nonetheless, the two countries could gain more from their relationship; China in terms of imports and Mozambique in terms of agriculture and rural growth policies, farming technologies and institutional capacity building[42].

Unfortunately, Mozambique is still not able to absorb lessons because of its inefficiency. The poor capacity of the Mozambican state to effectively implement agricultural policies, build and conserve agricultural infrastructure and ensure a concrete agricultural development, is considerably jeopardizing the possibility to gain some advantage from this partnership[43].

At the same time, the increasing Chinese interest in agricultural partnerships has raised concerns about potential land grab[44]. This is true especially if we consider the social and economic implications that the hosting country has to face trying to address the increasing vulnerability of traditional subsistence farmers[45]. In this respect it is important to stress that the agreements signed at a governmental level often disregard the interests and the rights of local populations. In fact, the implementation of Chinese interest means the displacement of Chinese workers in rural areas directly damaging the livelihood of local communities. Moreover, other issues can arise. For instance, the increasing competition between Mozambican and Chinese producers in local markets, the increase of cash crop production at the expense of food crop production for local consumption.

Chinese Presence Impact on Africa

As stated above, in the last decade China has improved and differentiated its investment in Africa.

China’s presence in African agriculture has a huge potentiality. First of all, it can contribute to agricultural growth and poverty reduction as well as provide useful lessons through its own experience.

Unfortunately, often potentiality is not matched because of the vulnerability of African institutions. In fact, Chinese investment is hindered by social, economic, political and environmental perspectives. Moreover, indigenous institutions also affect the outcomes of China’s investment in agriculture.

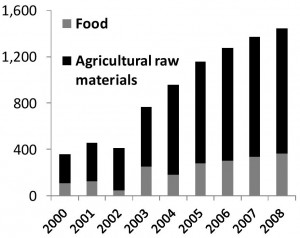

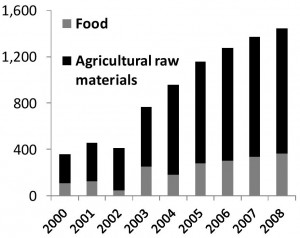

In order to address its food needs, China sources agricultural products and commodities from Africa. This process can produce two main results. On one hand, the demand of the Chinese market can result in growing profit and business for African farmers but, from another perspective, as already analyzed in the case of the Mozambican situation, Chinese presence can result in changes of the livelihood of local communities and in a decreasing role of local peasants in the local markets in favor of Chinese farmers.

Figure 3: Export of Sub-Saharan Africa to China (US$ millions)

Source: Shenggen Fan, Bella Nestorova, and Tolulope Olofinbiyi, “China’s Agricultural and Rural Development: Implications for Africa”, 2010[46]

Despite these two relevant main effects, it is definitely sure that Africa needs foreign financial assistance to develop its agricultural sector and that, in this respect, China is an important partner providing knowledge sharing on technology and production.

Moreover, Africa could learn lessons especially on agriculture and rural growth, evidence-base policy making, pro-poor policy and institutions and capacity.

As for the first point, African countries should increase their investment in agricultural infrastructure such as irrigation systems. In addition, investment in agriculture resources must be increased and tailored to the African context in order to be able to concretely address social needs.

As for policy making issue, African countries should gradually implement their policies. First of all, they could test policies in some selected district or community, and after having controlled results, governments could implement them nationwide. In this respect, monitoring and evaluation capabilities must be improved.

Furthermore, policies have to be targeted to the poor in order to reduce hunger and poverty. In this respect, a community base approach could turn out to be really positive. Programs should target vulnerable people in both rural and urban areas.

Unfortunately, African institutions lack the political power to attain their objectives. For this reason, African leaders should sustain their commitments to reform and provide more power to those institutions willing to cooperate with them. In addition, new institutional arrangements should be experimented to provide new development opportunities.

Notes

[1]Source: http://www.iprcc.org/userfiles/file/Li%20Jiali-EN.pdf

[2]FOCAC. 2012. The Fifth Ministerial Conference of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation Beijing Action plan (2013-2015). FOCAC. Source: http://www.focac.org/eng/zxxx/t954620.htm [2014, April 17].

[3]These major efforts to foreign countries should be materialized by increasing the number of agricultural technology demonstration centers in developing countries to 30, doubling the number of agricultural experts and technical personnel dispatched. Moreover, in 2009, at the 4th FOCAC ministerial meeting, Premier Wen Jiabao further announced eight new measures in increasing Chinese investments in African agriculture. These measures entailed the establishment of twenty demonstration centers and fifty agricultural technology groups in Africa to take part in the training of up to 2 000 agricultural technical personnel.

[4]Buckley, L., “Narratives of China-Africa Cooperation for Agricultural Development: New paradigms’?”, Future Agriculture CBAA working papers no 053, 2013.

[5]The Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program (CAADP) was established as part of NEPAD in July 2003 and focuses on improving and promoting agriculture across Africa. CAADP aims to eliminate hunger and reduce poverty through agriculture. It brings together key players – at the continental, regional and national levels – to improve co-ordination, share knowledge, success and failures, to encourage one another, and to promote joint and separate efforts to achieve the CAADP goals.

[6]Rex Ukaejiofo, “China-Africa agricultural co-operation Mutual benefits or self-interest?”, Center for Chinese Studies, Stellenbosch, South Africa, September 2014, p.14

[7]The Bandung Conference of Non-Aligned Nations was a meeting of Asian and African states, most of which were newly independent, and took place on April 18–24, 1955 in Bandung, Indonesia. The twenty-five countries that participated in the Bandung Conference represented nearly one-quarter of the Earth’s land surface and a total population of 1.5 billion people. The conference was organized by Indonesia, Burma, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and India and was coordinated by Ruslan Abdulgani, secretary general of the Indonesian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The stated aims of the conference were to promote Afro-Asian economic and cultural cooperation and to oppose colonialism or neocolonialism by any nation. The conference was an important step toward the Non-Aligned Movement. The participating countries were: Kingdom of Afghanistan, Burma, Cambodia, Ceylon, People’s Republic of China, Cyprus, Egypt, Ethiopian Empire, Gold Coast, India, Indonesia, Iran, Kingdom of Iraq, Japan, Jordan, Laos, Lebanon, Liberia, Libya, Nepal, Pakistan,Philippines, Saudi Arabia,Syria, Sudan, Thailand, Turkey, Yugoslavia, Democratic Republic of Vietnam, South Vietnam, Kingdom of Yemen

[8]Jiali, L., “Sino Africa Agricultural Co-operation Experience Sharing”,2014, March 19. Web source: http://www.iprcc.org/userfiles/file/Li%20Jiali-EN.pdf

[9]Brautigam, D., and X. Tang. “China’s Engagement in African Agriculture: Down to the Countryside”. China Quarterly, December, 2009.

[10]Yan, H., and Sautman, B., “Chinese Farms in Zambia: From Socialist to “Agro-Imperialist” Engagement?”, African and Asian Studies, 2010, pp. 307-333.

[11]One example of this can be demonstrated through the China State Farm Agribusiness Corporation utilizing Chinese preferential loans to buy farms in Zambia for agricultural development, primarily in grain, vegetable and livestock production.

[12]Chenchen Wu, “China’s Foreign Policy towards Africa.”, The School of Government and International Affairs, Durham University. United Kingdom. Web source: http://www.pol.ed.ac.uk/__data/assets/word_doc/0018/15633/chenchen_wu_paper.doc.

[13]South–South Cooperation is a term historically used by policymakers and academics to describe the exchange of resources, technology, and knowledge between developing countries, also known as countries of the global South.

[14]Buckley, L. (2013). Chinese Agriculture Development Cooperation in Africa: Narratives and Politics. IDS Bulletin, 44.4 Web source: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/(ISSN)1759-5436/issues

[15]FOCAC (2012), The Fifth Ministerial Conference of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation Beijing Action Plan (2013-2015), Forum on China Africa Cooperation, July 23. Web source: www.focac.org/eng/zxxx/t954620.htm

[16]Buckley, L. 2013. “Narratives of China-Africa Cooperation for Agricultural Development: New paradigms’?”. Future Agriculture CBAA working papers no 053.

[17]Davies estimated total aid to Africa between 1949 and 2006 to be valued at US$5.6 billion. Davies, P. (2006), “China and the End of Poverty: Towards Mutual Benefit?”, Diakonia Report, Sundyberg, Sweden: Alfaprint Press

[18]The One-China policy refers to the policy or view that there is only one state called “China”, despite the existence of two governments that claim to be “China”. As a policy, this means that countries seeking diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) must break official relations with the Republic of China (ROC) and vice versa.

[19]GOV (2010), “China-Africa Economic and Trade Cooperation”, Information Office, State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Web source: http://english.gov.cn/official/2010 12/23/content_1771603.htm

[20]Scissors, D. (2010), “Tracking Chinese Investment: Western Hemisphere Now Top Target”, The Heritage Foundation. Web source: http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2010/07/tracking-chinese-investment-western-hemisphere-now-top-target

[21]Helen Lei Sun, “Understanding China’s agricultural investments in Africa”, South African Institute of International Affairs, Occasional paper n.102, November 2009, p. 9.

[22]Sammis JF, ‘Statement by US Deputy Representative to ECOSOC John Sammis at the First LDC IV Intergovernmental Preparatory Committee’, US Mission to the UN, 10 January 2011. Web source: http:// usun.state.gov/briefing/statements/2011/154233.htm

[23]Chinese Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation, China–Africa Trade and Economic Relationship Annual Report, 2010.

[24]Ibid. p.17.

[25]Ibid. p.17.

[26]Ayodele, T., & Sotola, O. 2014. “China in Africa: An Evaluation of Chinese Investment”. IPPA Working Paper Series. Lagos.

[27]Amanor, K. S. 2013. “Chinese and Brazilian Cooperation with African Agriculture: The Case of Ghana”. Future Agriculture CBAA working papers no 052.

[28]It is a French research center working with developing countries to tackle international agricultural and development issues. It works with developing countries to generate and pass on new knowledge, support agricultural development and fuel the debate on the main global issues concerning agriculture.

[29]Rex Ukaejiofo, “China-Africa agricultural co-operation Mutual benefits or self-interest?”, Center for Chinese Studies, Stellenbosch, South Africa, September 2014, p.21.

[30]Li, X., Qi, G., Tang, L., Zhao, L., Jin, L., Guo, Z. And Wu, J., “Agricultural Development in China and Africa: A Comparative Analysis.”, Routledge. 2012.

[31]Li X. 2010. “Comparative perspectives in Development and Poverty Reduction in China and Africa.” IPRCC. Beijing.

[32]Brautigam, D., and X. Tang., “China’s Engagement in African Agriculture: Down to the Countryside”, China Quarterly, December, 2009.

[33]Wolfgang Bartke, “The Economic Aid of the PR China to Developing and Socialist Countries”, K. G. Saur, Munich, 1989, p. 92.

[34]Sérgio Chichava, “China in Mozambique’s agriculture sector: implications and challenges”, Institute of Social and Economic Studies (IESE), Maputo, November 2010, p. 5. Web source: http://www.iese.ac.mz/lib/noticias/2010/China%20in%20Mozambique_09.2010_SC.pdf.

[35]Brautigam D., Ekman SM., “ Briefing rumors and realities of Chinese agricultural engagement in Mozambique”, Oxford University Press, May, 28, 2012, p.6.

[36]Duncan Freeman, Jonathan Holslag, and Steffi Weil, “China’s foreign farming policy: can land provide security?”, Brussels Institute on Contemporary China Studies, 2009, p. 19.

[37]Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, “Green Super Rice for the Resource Poor in Africa and Asia”, Semi-Annual Report, submitted to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, July 2009.

[38]Brautigam D., Ekman SM., “ Briefing rumors and realities of Chinese agricultural engagement in Mozambique”, Oxford University Press, May, 28, 2012, p.8.

[39]Established in 2009, China-Africa Cotton Development Ltd joint-ventured by China-Africa Development Fund, Qingdao Ruichang Cotton Industrial Co., Ltd and Qingdao Huifu Textile Co., Ltd, with a plan to invest about $64.72 million US dollars, and actual investment of $52.08 million US dollars as of today. As the parent company, China-Africa Cotton invests in many projects in various African countries, including Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Chad,Togo and Mali. Company focuses on seed researching, plantation, cotton purchasing and processing, cotton seed oil processing and textile making.

[40]Asanzi P (2014). “UNDERSTANDING THE CHALLENGES OF CHINESE AGRICULTURAL INVESTMENTS IN AFRICA: AN INSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS”. Acad. Res. J. Agric. Sci. Res. 2(5): pp.76-87.

[41]Land law n° 19/97. Web source http://www.portaldogoverno.gov.mz/Legisla/legisSectores/agricultura/LEI%20DE%20TERRAS.pdf

[42]Roque, Paula C. (2009) “China in Mozambique: A Cautious Approach Country Case Study”, South African Institute of International Affairs Occasional Paper No 23.

[43]African East-Asia Affairs, the China Monitor, “China-Mozambique relations: support and governance challenges”, Center for Chinese Studies, issue 72, June 2012, p. 22.

[44]This attitude has induced some scholars to suggest that Chinese land grab would turn Mozambique into the first China’s agricultural colony: Horta, Loro (2008) „The Zambezi Valley: China‟s First Agricultural Colony?‟, Web source http://csis.org/publication/zambezi-valley-chinas-first-agricultural-colony

[45]Bräutigam, D. and Xiaoyang, T. (2009) “China’s Engagement in African Agriculture: Down to the Countryside”, The China Quarterly, 199: pp.686-706.

[46]Shenggen Fan, Bella Nestorova, and Tolulope Olofinbiyi, “China’s Agricultural and Rural Development: Implications for Africa”, China-DAC Study Group on Agriculture, Food Security and Rural Development, Bamako, April 27–28, 2010.