South Africa has a lot of improvements to make in terms of population’s physical accessibility, financial protection and acceptability of the current public health care system. The National Health Insurance offers hope to the disadvantaged but it will not be ready anytime soon leaving the current health care arrangements with their own vulnerability needing continued revamping. The government may need to stop being reactive but proactive in addressing the inequality that is fuelling the lack of access for a majority of the population

by Plaxcedes Chiwire

Deputy Director, Strategic Planning Unit (Health Economist) at Western Cape Department of Health, South Africa

Factors Influencing Access to Health Care in South Africa

Introduction

The World Health Organisation constitution articulates ‘the highest standard attainable standard of health as a fundamental right of every human being’, with the right to health including access to timely, acceptable, and affordable health care of appropriate quality (United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights; World Health Organisation, 2008). The WHO further state that the right to health is a fundamental part of our human rights and of our understanding of life in dignity. The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights article 25 also mentions health as part of the right to an adequate standard of living (United Nations, 1948). The 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights recognised the right to health as a human right (United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 1996).

Three sections in the South African constitution provide for the right to health care services. These provisions include reproductive health, emergency services, basic health care for children and medical services for detained individuals and prisoners (South African National Constitutional Assembly, 1996). However, being afforded the right to something does not necessarily translate into getting the service, more so the quality of care. The International Bill of Rights, of which most national constitutions are based on, awards human beings the most incredible freedoms. But on analysis on whether the implementation of these rights has undertaken, most countries fail the test dismally, including the health sectors in most of these countries. Despite some shortcomings South Africa has invested a lot into making sure that these rights are upheld.

The South African legislative framework supports the quest for universal health coverage, or to be less ambitious, that of purely quality health care for all citizens. Universal Health Care is a proponent of the World Health Organisation (WHO), which was the driving force into achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) by 2015. It has found a place within the expanded agenda of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the successor to the MDGs, after most nations failed to achieve the MDGs, South Africa included (Statistics South Africa, 2015). Target 3.8 of the SDGs alludes to achieving universal health coverage, with the inclusion of access to quality essential health care services, medicines and vaccines for all. The issue of access is however, silently alluded to in all the SDG 3 goals. Improved access is the key to unlocking any successful implementation, and achievement of the intended outcomes for SDG 3. The WHO describes access to health care as having physical accessibility to health services, financial affordability influenced by the household and the financial systems within the country and acceptability by the patients of the services provided to them (Evans, Hsu, & Boerma, 2013).

Provision of easy access to health care falls short in many aspects. The National Development Plan reiterates that poor implementation of policies is a problem and there is need to hold people accountable and allowing innovation if government is to succeed in any type of service provision (South African Department of the Presidency: National Planning Commission, 2012). The adoption of National Health Insurance by the South African government is a way forward in advancing universal health care. Several factors should be considered when wanting to attain an equitable access to care. It is not only the health centres that allow for patient access, but interactions amongst a broader socio-economic determinants and outcomes. Examples include demography, health seeking behaviour of individuals, burden of disease, geographical set up of the towns and rural areas, income, education, infrastructure and the economics shifts. Inequality is a major aspect in access to care and is measured mostly using income as proxy.

Population

Statistics South Africa (2016) estimated the 2016 mid-year population to be about 55.9 million, an increase from about 50.6 million in 2011. The public health sector is currently drowning under increased burden of disease and the government acknowledges the need to re-engineer primary health care. Increased migration has also contributed to the overburdened health system. A dissection of the current situation already shows an adult population riddled with a high burden of diseases, namely HIV/AIDs, tuberculosis (TB), non-communicable diseases and injuries (Statistics South Africa, 2016). The ageing of the population noted in some parts of the country also has an impact on disease burden, especially the non-communicable disease which affects the older population.

The HIV/AIDS prevalence of the total population for 2016 was estimated to be 12,7% and18,9% for those aged 15-49. The infant mortality rate for 2016 was projected to be 33,7 per 1 000 live births whilst life expectancy was 59.7 for males and 65.1 for females (Statistics South Africa, 2016).

Equity

If there is to be equitable quality health care in the country, efficient measures need to be put in place which includes further strengthening of health and wellness promotion programmes as preventative measures. The number of people on social grants increased from about 2.5 million to about 16.6 million between 1997 and 2015, an increase of 564%. The dependency level is becoming shockingly high and needs to be managed very carefully. The Gini co-efficient, a measure of income inequality, has not changed that much, with a slight increase from 0.6 to 0.679 between 1995 and 2009, then slightly declined to 0.63 in 2010 (World Bank, Development Research Group, 2016). This reflects high levels of inequality which have been attributed on the high unemployment rate i.e. 26.7% ending June 2016 (Statistics South Africa, 2016). Private medical aid caters for only 16% of the population and the rest are the responsibility of the government (South African Department of Health, 2015).

Financing and financial protection

South Africa has been experiencing a low growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) since 2015. The government has been forced to seriously consider cost containment measures, asking all departments to cut expenditure for the Medium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) period 2016/17 to 2018/19. South Africa’s credit rating as at June 2016 was Baa2 with negative outlook. This is one level above junk status and there is a possibility of a downgrade if the economic growth continues to be 0.1% in 2016 and 1.0% in 2017 as projected by the International Monetary Fund. The government health expenditure/GDP is estimated to be 4.2% and 4.1% for the private/GDP, totalling 8.3% above the required WHO recommendation (South African Department of Health, 2015). The incremental increase in the government’s health budget cannot sustain the substantial demand in health services. However, health outcomes remain poor, characterised by drug stock outs, long waiting hours, lack of cleanliness and safety problems amongst a multitude.

Jumare et al cites Berman (1995) as having concluded that the only way out for middle income countries, South Africa included was to reduce the growth in the health budget and focus on cost containment (Jumare, Ogujiuba, & Stiegler, 2013). This assertion seems to be the status quo for the government as a whole. The strategy was however criticised for being anti-poor and was likely to cause a diversion from neglected groups who so need easy and affordable access to health care. The only way to avoid this pathway is by continued ring-fencing of certain budgets an example being the Conditional Grant for HIV/AIDS, which will allow for free anti-retroviral treatment.

Continued no-fee service for maternal and child health care (MCHC) is another way to ensure consistent access. Gilson and Schneider note the increase in utilisation of services after the introduction of free MCHC and the failure to translate to a reduction in maternal and child mortality rates or increased hospital deliveries (Gilson & Schneider, 2006). The country still grapples with late bookers for Basic Antenatal Care (BANC), which is a risk for increased maternal and antenatal mortality. Free user fees, even for a few services is, however, a catch 22 situation. The numbers of people falling into the debt trap has risen resulting in the portion of the population that could afford medical aid narrowing. There is a possibility the 16% covered in 2015 would be much lower by the end of 2016 owing to the current economic hardships. The National Health Insurance (NHI) white paper (released 10 December 2015) notes the spending by the 83 medical aid schemes to be six times higher than Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). This means the public sector will have to cater for new clients and this will result in huge service and financial pressures. How then does the government balance their health account without asking the public to pay just a little bit extra?

Increased taxation, debt and general budget support from donors seem to be the only sustainable solution in the long term. With the NHI White Paper currently being commented on, it waits to be seen how the financial arrangements will pan out. Clarity on the provider mechanisms and the role of the provinces in procuring services are not clear. Developed countries have institutions in place managing value-based reimbursement/fee for value structures, a step ahead of value based care/fee for service. Money is a major factor in deciding whether to seek health care or self-medicate. The following section looks at factors influencing these decisions.

Health Seeking Behaviour

Despite the heavy efforts by the national and provincial departments of health to promote access to treatment, individual’s health seeking behaviours is the major factor influencing access to health care. Health seeking behaviours are influenced by education levels, cultural beliefs, gender, financial strain or personal perception of health centres. The health care environment has become more consumer driven and several options of where to seek care are available, making it more important to have personal-centred services in order to attain increased patient satisfaction from the system and continued use of the facilities/services.

A study in the North West provinces refutes this assertion, noting that urban counterparts rated their health much better in comparison to rural counterparts (Van der Hoeven, Kruger, & Greeff, 2012). Both agreed to availability of care though the quality of care was below expected standards, with staff failing to deliver on the patient’s requests. Adequately equipped facilities tend to be a pull factor while the opposite pushes patients away. Continued strengthening of the service delivery platform and quality improvement in the public health sector should take priority, which it currently does if the public perceptions are to be reversed. Operation Phakisa Ideal Clinic is a government initiative meant to ensure all clinics are up to the gold standard. It is an online tool which all clinics are evaluated against different criterion and the information is available to the public.

In the same study, economic circumstances were poorer for rural community members in terms of not only affordability of health care but also transportation money needed to seek treatment (Van der Hoeven, Kruger, & Greeff, 2012). Ultimately, socio-economic factors such as income exacerbate the morbidity and mortality amongst the poor. South African children are 10 times likely to die from diarrhoea if they come from poverty stricken household in comparison to those who are better off (Chola, Michalow, Tugendhaft, & Hofman, 2015).

Traditional healers become the go to doctors. Some are bogus whilst some have their capabilities to treat other ailments. They have been crucial in the fight against HIV/AIDS and TB. The Department of Health (DoH) established the Traditional Healers Bill, to

“provide for a regulatory framework to ensure the efficacy, safety and quality of traditional health care services to provide for the management and control over the registration, training and conduct of practitioners, students and specified categories in the traditional health practitioners profession and to provide for matters connected therewith”. (Ministry of Health, 2003)

MacKian (2014) reiterates the need to design health service delivery strategies in a way sensitive to the local dynamics of the community (MacKian, 2004). The community information systems which are aligned to mostly the Home and Community Based Care (HCBC) platform of the government departments is one way to strengthen the health promotion. Children have been reported to die at home from diarrhoea due to the parent’s lack of knowledge and information on the diseases and what steps to take for treatment (Mulaudzi, Phiri, Mmamakwa, & Mataboge, 2016). The redesign of the HCBC service platform creates the potential for capacity development; enabling a more responsive health system that pro-actively engages households on matters that impact on wellness. The Community Health Workers (CHWs), under this platform have been applauded for increasing the adherence in HIV and TB treatment, child and maternal programmes through their home support visits. However, the HCBC in the country faces its own challenges of under paid community health care workers resulting in high turnovers. In provinces such as the Western Cape, the Non-Governmental organisations are contracted by the DoH to run the programme. However, in areas like Gauteng, the DoH has faced court action. The CHWs demanded to be recognised as government workers with permanent employment contracts, a demand with far reaching consequences in terms of budgets especially in a fiscal constrained environment.

The DoH came with policies on integration of TB/HIV treatment in the primary health care (PHC) services, decentralization of the management of multi-drug resistant (MDR) TB from specialized to lower levels of care and strengthening community-based care. The main purpose is to try and deal with the vertical organisation of services likely to weaken the system as patients are required to make separate visits for different ailments. The integration not only has helped in improving health outcomes, but has an added advantage to those seeking treatment. Not only do they get treatment in one place, but they save in terms of travelling, food and time costs. There is general consensus that once the economic and financial costs are taken care of, an individual’s chances of seeking treatment increase. However, a point of contention that has affected patients’ access to treatment has been the separate treatment rooms and or patient folders for those with HIV/AIDS (Zwarenstein, et al., 2011). Stigma is still very rife. Patients fear being betrayed by the folder colour or the designated room for HIV patients, resulting in either changing the centre of treatment or ultimately defaulting. The issue of human rights versus operational design to streamline processes as part of lean management comes into question. Would we rather prioritise human rights over running a centre at optimal efficiency?

Despite the formation of adherence groups, TB remains the main cause of death, dating back to 2009 (12%) (Soul City and SA National Department of Health, 2015) increasing to 21,8% in 2014 (Statistics South Africa, 2015). The Western Cape has the highest number of TB infections in South Africa. South Africa as a whole has records 1% of the total population as being infected by TB. Co-existence of TB and HIV/AIDS has also increased the number of TB infections. WHO estimates the percentage to be between 60 and 73 (Soul City and SA National Department of Health, 2015). High defaulting rates (6.2% in 2013) have resulted in the continued spread of TB despite the high cure rates.

Infrastructure, Water and Sanitation

Housing and infrastructure has contributed immensely to lack of access in health care. The link between poor housing infrastructure and poor health status is pronounced in the South African context. Lack of access to proper housing has inevitably resulted in factor contributing to lack of access to health care. The pre-apartheid era detected who could access what forms of houses due to the economic and political conditions. Such conditions widened the gap between the poor and the rich, leaving more indigent households dependent on the state for provision of housing, water and sanitation. The existence of huge informal settlement in the country, has the government grappling to provide “better housing”, by upgrading 750 000 households by 2019 within informal settlements. The National Department of Human Settlements’ main aim is to provide households, “with secure tenure and access to basic services, such as water and sanitation,” (South Africa’s National Treasury, 2016). In 2011, access to piped water (inside the yard) was at 73.4% and increase from 69.4% in 2007 (Statistics South Africa, 2016). MDG 7[1] target of 74.7% had been surpassed by the year 2012. Improved access to sanitation had been achieved with 75% of the population (Chola, Michalow, Tugendhaft, & Hofman, 2015).

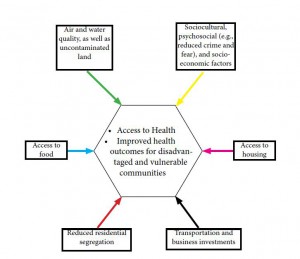

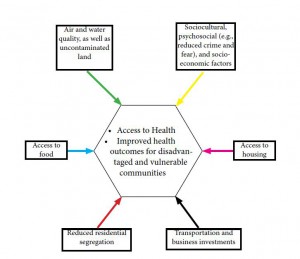

Figure 1: Built Environment Factors Affecting Public Health

Source: Adapted from Srinivasan, O’Fallon & Deary 2003

The government’s continued efforts to bring water to the doorsteps of every household is commendable as a way to circumvent water-related diseases such as diarrhoea which have found a place on the South African Health calendar i.e. from November to May (Western Cape Government, 2016). Diarrhoea is the second leading cause of death in children under 5, accounting for 14.9% in 2014 (Statistics South Africa, 2015). With all the efforts, climate change has had its own unforeseen impact. In 2015, the Southern African region started experiencing a prolonged drought and water access was disrupted, even to those with household tapes thereby increasing the likelihood of diseases like diarrhoea. The public health sector needs to be ready at any point time cease to focus on a particular season.

Several studies allude to poor and inadequate housing leading to a multitude of health problems, namely asthma, depression air pollution, obesity, substance abuse and aggressive behaviour, an ingredient for non-accidental injuries (Srinivasan, O’Fallon, & Dearry, 2003). By extension, the access to health is diminished. A major cause for concern is the increase in TB related infections and deaths within South Africa.

Distance

Spatial planning in the urban and rural areas is far from similar. In areas like the Eastern Cape where the rural area is not well developed, health centres are very far from each other, so are the referral centres. It is difficult to get an ambulance to a place on time due to the geographical terrain. The distance decay further complicates the issue of bringing health care to the rural population. There are huge disparities in the urban and rural population. Performance indicators are therefore structured differently, an example being the response rate for urban ambulances which is measured with a 15 minute target whilst in rural areas it is a 40 minute target. A few seconds can determine life or death. Forty minutes is just too long. The same applies to other provinces rural areas. Distances between clinics and hospitals leave much to be desired. Though in the urban areas, the 2km rule between health centres has been well pronounced during urban planning, access to those centres is still poor and lack of finances, specifically transport money, is mostly to blame. In the urban area, studies show that 2/3 of South Africans reside less than 2km from the health centres, 90% reside within a 7 km range (McLaren, Ardington, & Leibbrandt, 2014).

Despite having a social security in place, offered through the South Africa Social Security Agency (SASSA) grants and Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF) for those unemployed, the amounts are menial and cannot cover transport costs. In most cases resources are shifted from household use to transportation when client is already in an emergency situation, affecting their health outcomes in a negative way.

Related to housing and infrastructure within the informal settlements, is the lack of clear transport routes and street names, easily identifiable. In most provinces, the Emergency Medical Services’ (EMS) response rates have been lowered by poor performance in the informal dwellings. The situation has becoming dire with some residents believing the response times are only poor in the informal areas because of racial or class disparities and this has resulted in attacks against the EMS support services. In the Western Cape, gang violence (Etheridge, 2016), criminal elements have been noted as a factor due to the targeting of Mobile Data Terminal (MDT) devices installed in ambulances (Medical Brief, 2016) resulting in attacks on the EMS staff. While the major concern is a life being lost if an ambulance arrives late, it is now clear that lives can be lost for those responding to emergency calls. It makes one wonder whether the “urban penalty” (Kearns, 1988) actually exists in South Africa. The penalty assumed urban areas were associated with poor health than rural areas due to poor sanitation and housing, overcrowding and other social ills in comparison to rural areas which are in essence more spacious.

Conclusion

South Africa, may be a leading economy in Africa, but it has a lot of improvements to make in terms of population’s physical accessibility, financial protection and acceptability of the current public health care system. The NHI offers hope to the disadvantaged but it will not be ready anytime soon leaving the current health care arrangements with their own vulnerability needing continued revamping. The government may need to stop being reactive but proactive in addressing the inequality that is fuelling the lack of access for a majority of the population.

References

Chola, L., Michalow, J., Tugendhaft, A., & Hofman, K. (2015, April 17). Reducing diarrhoea deaths in South Africa: costs and effects of scaling up essential interventions to prevent and treat diarrhoea in under-five children. BMC Public Health, 15-394. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1689-2

Etheridge, J. (2016, 9 14). News24. Retrieved 10 10, 2016, from News24: http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/concern-as-another-ambulance-is-attacked-in-cape-town-20160912

Evans, D. B., Hsu, J., & Boerma, T. (2013). Universal health coverage and universal access. Retrieved from Bulletin of the World Health Organization : http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/91/8/13-125450/en/

Gilson, L., & Schneider, H. (2006). The impact of free maternal health care in South Africa. In M. Berer, & R. T. Sundari, Safe Motherhood Initiatives: Critical Issues. Oxford: Blackwell Science, for Reproductive Health Matters. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/dfid-research-outputs/the-impact-of-free-maternal-health-care-in-south-africa

International Monetary Fund . (2016, July). World Economic Outlook Update . (IMF, Producer) Retrieved 10 13, 2016, from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/update/02/

Jumare, F., Ogujiuba, K., & Stiegler, N. (2013, July). Health Sector Reforms: Implications for Maternal and Child Healthcare in South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 4. doi:Doi:10.5901/mjss.2013.v4n6p593

Kearns, G. (1988). The urban penalty and the population history of England. In A. Brandstrom, & L. Tedebrand, Society, Health and Population During the Demographic Transition (pp. 213–236). Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell International.

MacKian, S. (2004). A review of health seeking behaviour:problems and prospects. Manchester : University of Manchester.

McLaren, Z., Ardington, C., & Leibbrandt, M. (2014, 10 20). Distance decay and persistent health care disparities in South Africa. BMC Health Services Research, 14:541. doi:DOI: 10.1186/s12913-014-0541-1

Medical Brief. (2016, August 10). Paramedics demand protection against violent attacks. Retrieved from Medical Brief: http://www.medicalbrief.co.za/archives/paramedics-demand-protection-violent-attacks/

Ministry of Health. (2003). Traditional Health Practitioners’ Bill. Pretoria: Ministry of Health .

Mulaudzi, F. M., Phiri, S., Mmamakwa, D. M., & Mataboge, P. (2016, May 6). Challenges experienced by South Africa in attaining Millennium Development Goals 4, 5 and 6. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 2(26).

Soul City and SA National Department of Health. (2015). Literature Review of TB in South Africa. Pretoria: Soul City.

South African Department of Health. (2015). National Health Insuarance in South Africa: White Paper. Pretoria: National Department of Health .

South African Department of the Presidency: National Planning Commission. (2012). National Development Plan 2030. Pretoria: Department of the Presidency.

South African National Constitutional Assembly. (1996, May 8). Department of Justice. Retrieved October 16, 2016, from Legislation: http://www.justice.gov.za/legislation/constitution/saconstitution-web-eng.pdf

South African National Department of Health . (2016, 10 5). Essential Drugs Programme (EDP). Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.za: http://www.health.gov.za/index.php/essential-drugs-programme-edp

South Africa’s National Treasury. (2016). National Department of Human Settlements 2016/17 Budget. Pretoria: National Treasury.

Srinivasan, S., O’Fallon, L., & Dearry, A. (2003). Creating healthy communities, healthy homes, healthy people: initiating a research agenda on the built environment and public health. American Journal of Public Health, 93(9), 1446–1450.

Statistics South Africa. (2015). Millennium Development Goals: Country report 2015. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa.

Statistics South Africa. (2015). Mortality and causes of death in South Africa,2014: Findings from death notification. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa .

Statistics South Africa. (2015). Mortality and causes of death in South Africa,2014: Findings from death notification. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa.

Statistics South Africa. (2016). Mid-year population estimates. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa .

Statistics South Africa. (2016, 10 11). Statistics South Africa Website. Retrieved from Statistics South Africa: http://www.statssa.gov.za

United Nations. (1948). United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948. Geneva: United Nations .

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights . (1996). International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Geneva: OHCHR.

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights; World Health Organisation. (2008). The Rights to Health Fact Sheet no. 31. Geneva: United Nations.

Van der Hoeven, M., Kruger, A., & Greeff, M. (2012, June). Differences in health care seeking behaviour between rural and urban communities in South Africa. International Journal for Equity in Health, 11(31). doi:10.1186/1475-9276-11-31

Western Cape Government. (2016, 10 11). News and Speeches News and Speeches Archive. Retrieved from Western Cape Government: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/news/diarrhoea-season-here

World Bank, Development Research Group. (2016). Retrieved October 5, 2016, from World Bank Gini Index: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=ZA

Zwarenstein, M., Fairall, L., Lombard, C., Mayers, P., Bheekie, A., English, R., . . . Bateman, E. (2011, April 21). Outreach education for integration of HIV/AIDS care, antiretroviral treatment, and tuberculosis care in primary care clinics in South Africa: PALSA PLUS pragmatic cluster randomised trial. British Medical Journal, 342-2022. doi:10.1136/bmj.d2022

[1] Halve, by 2015, the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation