Using the example of access to FSL glucose monitoring system, this report aims to highlight the fundamental problems with localist decision making on healthcare provision in England where the existing system of devolved power to Clinical Commissioning Groups is promoting a landscape of unequal access to medical care

By Rebecca Barlow-Noone *

Student of Medical Sciences at the School of Biological Sciences, University of Leeds (UK)

The NHS Postcode Lottery: How the Decision-Making Power of Clinical Commissioning Groups is Preventing Standardised, Equal Access to the Abbott Freestyle Libre in England

The existing system of devolved power to Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) is promoting a landscape of unequal access to medical care across the country, as demonstrated by recent media coverage regarding the flash glucose monitoring system, the Freestyle Libre (FSL). Demands must be made to address the unnecessary multi-tiered system of nationalist and localist decisions on NHS healthcare provision, which is impeding equality of care in England.

To understand the heart of the problem, the creation of CCGs must be understood. CCGs were established to realise demands made under the Health and Social Care Act of 2012 by allowing more localist decision making on healthcare provision and budgeting, in relation to Liberal Democrat ideology (The King’s Fund, 2013); yet this is a case where political ideology has overridden the true needs of the NHS.

Whilst localism appears progressive by enabling (in theory) the needs of local people to be prioritised, the responsibility devolution to CCGs has allowed healthcare to become non- standardised across England. With 207 separate decisions on access to healthcare and medicines, it was inevitable that a healthcare postcode lottery would emerge; and due to media coverage of FSL access, the issue is finally coming to light to the public.

Using the example of access to FSL, this report aims to highlight the fundamental problems with localist decision making on healthcare provision.

Firstly, responsibility devolution to CCGs causes multiple duplications of evaluation in items without NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) recommendation. The FSL, which became available on the NHS drug tariff in November 2017 through the NHS Business Services Authority (BSA), still lacks a Technology Approval (TA) from NICE. Without a TA, which legally binds CCGs to prescribe the technology according to NICE guidelines, CCGs are able to decide if the FSL can be supported on the budget in their area.

Responsibility devolution to CCGs has led to them becoming ‘the dominant operational unit within the NHS’ (Speed and Gabe, 2013, 571), where patient access is determined on their local CCG’s perception of clinical evidence and cost-benefit.

The gap between centralised decision-making and local decision-making to permit FP10 prescriptions for the FSL optimises the disorganised system currently in effect. With BSA approval on to the NHS Tariff, it would be expected that the NHS constitution is respected and funding provided to all based on ‘clinical need’ (DHSC, 2015), needs which have been defined by the Regional Medicine Optimisation Committees (RMOCs). RMOCs were created in response to the Accelerated Access Review: Interim Report, published in October 2015, which aimed to ‘reduce unnecessary barriers [to accessing medicines]’ when they are not approved by NICE (NHS England, 2016). Theoretically, this should have been the answer to national access to FSL.

Yet this is far from the case. As of 20th August 2018, 126 of the total CCGs have agreed to put FSL on their budget plan, and a further 6 have committed to follow RMOC guidelines once delivery plans are set (Cahm, 2018b). This means currently 62.21% of the estimated type 1 population in England currently has the Libre available on their CCG’s budget (Cahm, 2018a).

The irony in the cautious uptake of the FSL by CCGs is that the 2010 White Paper, one of the driving documents towards NHS reform and the establishment of CCGs, demanded for changes due to ‘poor comparative outcomes in relation to mortality rates’ for acute diabetes complications (Speed and Gabe, 2013, 565). It would therefore be expected that improving complications outcomes should be a top priority for all CCGs.

Yet even within the CCG areas accepting to fund FSL, eligibility criteria set by CCGs varies across England. RMOCs created comprehensive guidelines for FSL access for CCGs to follow. However, the guidelines CCGs are adopting have not been standardised. 106 CCGs are currently adopting RMOC recommendations verbatim, 24 CCGs have edited RMOC criteria, and 2 CCGs have created bespoke criteria (Cahm, 2018b). This is far from RMOC’s purpose to ‘eliminate duplication of medicines evaluation’ by ‘bringing these activities to the regional level’, as described by Dr Keith Ridge (NHS England, 2016). Without legal binding to RMOC decisions (Kar, 2018a), there remains little strength in unifying decision-making and bringing national guidelines to the local level, thus disregarding the very purpose RMOCs were created.

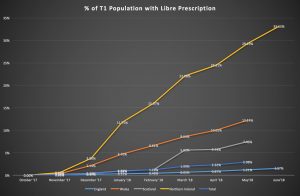

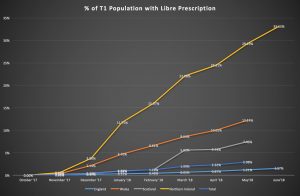

The problem with access to FSL in England due to CCG funding and access restrictions is evident when compared with access in Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales. Since national approval for FSL on FP10 forms, Northern Ireland (NI) is now prescribing FSL to 33.25% of the population with Type 1, Wales 12.24%, and Scotland 7.46%, compared to 1.57% in England (fig. 1: Cahm, 2018a).

Fig 1. Cahm, 2018a

The difference being that England puts prescribing power into the hands of local CCGs rather than higher national bodies. In the other nations, such as NI, the Libre was available on prescription to all, with access pathways determined at a national level by the Regional Diabetes Network in December 2017 (Brogan et. al, 2017). This was delivered to all five NHS NI trusts for implementation, to prevent variation in care, with all areas prescribing (Brogan et. al, 2017).

With almost a year passing since FSL was accepted on to the Tariff for FP10 prescription, the comparative figures for England are not acceptable. To combat the slow uptake, Partha Kar suggests enforcing a requirement for all items on the NHS Tariff to reach ‘100% national access within one year’ (2018b), which would improve access within the bounds of the current system. If

NI is able to provide national access with such a high uptake, it should be expected that similar figures are found in England.

Another argument made by CCGs is the cost compared to the base level cost of test strips; yet this is proven to be an unsubstantiated argument in many cases. Preventing access to FSL based on short-term budget does not take into account downstream intervention costs. Total diabetes costs to the NHS, assuming without inflation, is projected to rise to £16.9 billion by 2035/36 (Diabetes UK, 2014, 9). With 80% of diabetes costs currently due to complications (Diabetes UK, 2014, 7), and the likelihood of more price hiking in the future based on the 86.1% price increase over the last decade (NHE, 2016), the NHS must take greater steps in the prevention of complications. FSL may cost more than 4 test strips per day on the current market, but the overall cost of improving glycaemic control using FSL ‘can be less than those that arise from self-monitoring’, when targeting most needed groups as advised by RMOCs (Kar, 2018a).

Furthermore, the potential long-term cost benefits of using FSL to prevent complications are shown in improvements to Glycaemic Variability (GV). The IMPACT study, the largest trial so far of 239 participants with well controlled type 1 diabetes, found that the Freestyle Libre reduced time in hypoglycaemia by 38% and reduced GV (Bolinder et. al., 2016, 2258). Although there was minimal change in HbA1c, current evidence shows increased GV is an important risk factor directly responsible for the pathogenesis of vascular diabetes complications (Hirsch, 2015, 1612). With type 1 complications costing the NHS approximately £800,000 per year based on 2010/11 figures (Diabetes UK, 2014), it is imperative, both for patients’ quality of life and the NHS budget, to take preventative action against complications. From this perspective, FSL can be seen less as an economic hindrance, but an investment in preventative care.

In summary, in the short term, the problem of equal access within the NHS must be addressed. For FSL and other treatments aimed to reduce future complications, reduce downstream intervention costs and improve quality of life, it is imperative that the NHS takes greater steps to unify decisions made on diabetes healthcare.

If a true ‘national’ health service is to be maintained, systematic change is needed. Patient access should be decided at a national level in concurrence with FP10 approval on the NHS Tariff, and should not be in the hands of local CCGs. NHS England must make efforts to improve medical evaluation stages, using the systems in NI, Scotland and Wales as an example. It should not require lengthy multi-tiered systems of authorisation, which both increases time before patient access and duplicates evaluation.

References

Bolinder, J., Antuna, R., Geelhoed-Duijvestijn, P., Kröger, J., Weitgasser, R. 2016. Novel glucose- sensing technology and hypoglycaemia in type 1 diabetes: a multicentre, non-masked, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 388(10057), pp.2254-2263

Brogan, J., Hinds, M., Harper, C. 2017. Letter to Trusts Chief Executives. 4 December.

Cahm, C. 2018a. July Update – CCGs Under Pressure! [Online]. [Accessed 24 August 2018]. Available from: http://www.t1tenor.com/2018/07/july-update-ccgs-under-pressure.html

Cahm, C. 2018b. August Libre Update – Data, data and more data! [Online]. [Accessed 24 August 2018]. Available from: http://www.t1tenor.com/2018/08/august-libre-update-data-data-and-more.html

The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). 2015. The NHS Constitution for England. [Online]. [Accessed 24 August 2018]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-nhs-constitution-for-england/the-nhs-constitution-for-england#principles-that-guide-the-nhs

Diabetes UK. 2014. The Cost of Diabetes Report. [Online]. London: Diabetes UK. Available from: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/resources-s3/2017-11/diabetes%20uk%20cost%20of%20diabetes%20report.pdf

Hirsch, I. 2015. Glycemic Variability and Diabetes Complications: Does It Matter? Of Course It Does! Diabetes Care. 38. pp1610-1614.

Kar, Partha. 2018a. Letter to CCG Accountable Officers, CCG Clinical Leaders, and Directors of Commissioning Operations. 30 January.

Kar, Partha. 2018b. Interview with R. Barlow-Noone. 20 August, Manchester.

NHS England. 2016. Regional Medicines Optimisation Committees. [Online]. [Accessed 23 August 2018]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/medicines/regional-medicines-optimisation-committees/

Speed, E. and Gabe, J. 2013. The Health and Social Care Act for England 2012: The extension of ‘new professionalism’. Critical Social Policy. 33(3). pp. 594-574.

The King’s Fund. An alternative guide to the new NHS in England. [Online] [20 August 2018]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8CSp6HsQVtw

*About the Author

Rebecca Barlow-Noone currently studies Medical Sciences at the University of Leeds, and is the co-founder of DiaTravellers, an online travel platform for people with diabetes. She represents the UK as the Young Leader in Diabetes for the International Diabetes Federation, and is on the Diabetes UK Young Adults Panel.