IN A NUTSHELL Author's NoteThe 14th-century hospital of San Giovanni di Dio in Florence has, since the late 19th century, evolved into a specialized center predominantly focused on cardiovascular surgery. Decommissioned in 1983, the institution now calls for initiatives aimed at its enhancement, protection, and, above all, its conversion to a social-medical-sanitary use that will rescue it from its evident and growing underutilization. This impetus to capture the attention of the relevant authorities has been expressed through an Exhibition, complete with a catalog and parallel events. The Exhibition, "Tools for Healing: A Journey Through the Centuries from the Etruscan-Roman Era to the Robot. Testimonies from Tuscan Museums", aims to trace the milestones of progress in Tuscan (and interregional) surgery: from Etruscan-Roman and pre-Columbian surgical instruments, through the 18th-century technological innovations that codified the first specialized branches of medicine, to robotic surgery that represents the future of the discipline

By Dr Esther Diana

Architect, Historian of Healthcare and Healthcare Architecture

Tools for Healing

A Journey Through the Centuries from the Etruscan-Roman Era to the Robot

Testimonies from Tuscan Museums

Italian translation HERE

From the display of Etruscan-Roman and pre-Columbian surgical instruments viewers have an opportunity to explore the evolution of surgery from the 19th century to the present.

The Exhibition “Tools for Healing: A Journey Through the Centuries from the Etruscan-Roman Era to the Robot. Testimonies from Tuscan Museums” will be held from February 14 to May 9, 2025, at the Biblioteca Marucelliana in Florence, via Cavour 43.

The Exhibition poster

The history (1380 until today) of the ancient hospital of San Giovanni di Dio in Florence is a case study of the history and progress object of the Exhibition.

It is currently awaiting development that reflects its unique healthcare legacy—especially in the field of surgery, which established its reputation as an institution of excellence during the 19th and 20th centuries.

The Exhibition follows a philological storyline divided into four sections, each serving as an thematic synthesis. The first section, “Surgery in Archaeological Evidence”, highlights historical background of the hospital San Giovanni di Dio.

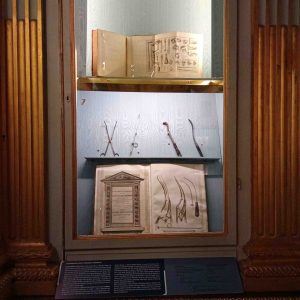

Entrance to the Exhibition

The Etruscan-Roman instrument room

The second section, “From Empirical Surgery to Vesalius”, highlights the crucial role that anatomical advances have played in the development of surgery and medicine in general. In the same space, the third section, “Military Surgery”, is dedicated to treatises by Ambroise Paré (1510-1590) and Giovanni Alessandro Brambilla (1728-1800), and displays three cases from Brambilla’s Armamentarium Chirurgicum.

Giovanni Alessandro Brambilla, Instrumentarium chirurgicum militare viennense, 1781 and urology tools

Finally, the fourth and most extensive section, “The Surgery of the Future”, acts as a bridge between the advancements achieved in the 19th and 20th centuries in general surgery, orthopedics, urology, and cardiac surgery, and the cutting-edge techniques of today and tomorrow: namely, minimally invasive and robotic surgery.

The scientific project and the curation of the Exhibition are led by Architect Esther Diana and Professor Francesco Tonelli, Emeritus in Surgery University of Florence.

Starting with History

In 1380, the Florentine merchant Simone Vespucci founded a hospital in Florence, near his family residence in the Santa Maria Novella district, intended for the impoverished – primarily wool workers. However, political and economic difficulties hindered the development of the institution, which remained essentially an almshouse until 1587.

Its transformation into a healthcare institution began in 1587, when the Grand Duke Francesco de Medici assigned this semi-abandoned facility to the Fatebenefratelli, a Counter-Reformation Order that was strongly supported by the Church and, as a result, warmly received at the Florentine court. The original “hospitaletto dei Vespucci” dedicated to Santa maria dell’Umiltà opened its doors immediately – as evidenced by the early Libri degli Infermi (Books of the Sick) from 1607 – with a ward arranged for 17 beds.

With the backing of the Church and the devoted care of the Brothers, the institution quickly succeeded, and in 1698 it was dedicated to San Giovanni di Dio in honor of the Order’s founder, Juan Ciudad, who was later canonized.

As a religious entity, the hospital was independent of state authority, a status that allowed it to be exempt from the public health regulations imposed during epidemic crises (notably plague and typhus) and to maintain full autonomy until the dissolution of the Order in 1866. This independence, determined in part by the type of care provided by the Brothers – mainly treating fevers (by reducing fever peaks through bloodletting or herbal infusions and decoctions), wounds, cuts, tooth extractions, and realigning limbs after falls or blows – transformed it into a specialist hospital where careful surgical procedures were largely carried out by the friars themselves.

The 17th century, and especially the 18th, represented the “golden age” of the complex, which significantly expanded its structure according to the architectural style typical of the Order – a style also adopted by other hospitals – characterized by an infirmary on the upper floor and a monumental entrance hall with a double, bi-directional staircase.

Monumental entrance hall of San Giovanni di Dio hospital, Florence

Towards Surgical Excellence

By the late 19th century, the hospital had increasingly emphasized its surgical function, bolstered by the presence of highly skilled medical professionals of both outstanding competence and humanity. By 1901, radiology, dentistry, and laboratory services were already in operation; in 1907, Florence’s first nighttime emergency service was established, paving the way for the creation of outpatient clinics in ophthalmology, otorhinolaryngology, urology, general medicine, and pediatrics by 1940.

During the 20th century, surgical activities intensified, particularly in oncological treatments involving complex abdominal and thoracic procedures. In the mid-1950s, a new frontier was opened – the first in Tuscany and among the first in Italy – in vascular and cardiac surgery. In the subsequent years, San Giovanni di Dio became a center of high specialization in these fields, acquiring a heart-lung machine; at that time, it was one of only two in Italy, the other being at Niguarda Hospital in Milan.

The heart-lung machine, 1957

This machine – now exhibited – enabled extracorporeal circulation, allowing surgeons to operate on a still, open heart to correct congenital defects, treat acquired or traumatic conditions, and eventually perform heart and heart-lung transplants.

Early experimental heart-lung machines were developed by John Heysham Gibbon (1903-1973) in 1937 and later applied in humans in 1953, managing to exclude the heart from circulation for approximately thirty minutes.

The exhibited heart-lung machine was purchased in Paris in 1957 for 890,600 Lire. Its cardiac function (circulation) was achieved through a system of keys (“fingers”) that propelled the blood in a coordinated and continuous manner, while its respiratory function (oxygenation) was provided by rotating discs within a cylinder.

The detailed focus on the heart-lung machine in the Exhibition underlines a pivotal moment in surgical practice – a point of departure from traditional methods. While archaeological artifacts show surgical instruments whose general design remains in use even in the 18th and 19th centuries, the heart-lung machine introduces us to a realm of highly technological surgery.

The fourth section of the Exhibition documents the advances achieved from the 18th century onward: the introduction of anesthesia, the discovery of pathogenic microorganisms, the advent of antiseptic and aseptic techniques, the ability to perform blood transfusions thanks to the identification of blood groups and the Rh factor, improvements in suturing techniques, the discovery of antibiotics, and the testing of biocompatible prosthetic materials – all fundamental in ensuring increasingly infection-free, less invasive, and less painful surgical interventions. Surgery has expanded into previously uncharted territories such as the abdomen, thorax, heart, major vessels, and skull. At the end of the 20th century, further innovations from physics and new materials led to the creation of flexible endoscopic instruments, which, using fiber optics or miniaturized cameras, allowed for effective endoscopic surgeries for biopsies, polypectomies, dilation of stenoses, and stone removal.

And finally, the surgery of today, already looking to the future: since development in 2000 of robotic surgery has emerged. This computerized system of sophisticated laparoscopic instruments, controlled by the surgeon from a remote console, offers enhanced three-dimensional and magnified vision, and movement precision that rivals or even surpasses that of the human wrist.

Introduction to robotic surgery

Conclusion

In conclusion, this Exhibition has a dual purpose. First, it serves to educate – especially young audiences – about a scientific journey of progress that, although largely overlooked, deserves thorough recognition and study as the outcome of extensive research, dedication, and the commitment of many surgeons who over the centuries have made the well-being of the individual a core ethical and moral principle. Second, as noted at the outset, it aims to prevent an institution of significant historical value from falling into oblivion, or worse, being ensnared by political and real estate speculation. San Giovanni di Dio remains a cherished institution among the people of Florence, awaiting only the acknowledgment of higher authorities to resume its rightful role in healthcare.