Globalized in 1995 by the TRIPs Agreement, humanity’s dominant mechanism for encouraging innovations involves 20-year product patents, whose monopoly provisions enable innovators to reap large markups or royalties from early users. Reliance on monopoly rents in the pharmaceutical sector is problematic for two main reasons. First, it imposes great burdens on poor people who cannot buy patented treatments at monopoly prices and whose specific health problems are therefore neglected by pharmacological research. Second, it discourages pharmaceutical firms from suppressing diseases by fighting them at the population level. Both problems can be much alleviated by establishing a supplementary alternative reward mechanism that would invite innovators to trade their monopoly privileges on a patentable pharmaceutical for impact rewards based on the incremental health gains produced with it. Such an international Health Impact Fund (HIF) would create powerful new incentives to develop pharmaceuticals against diseases concentrated among the poor, rapidly to provide such remedies with ample care at very low prices, and to deploy them strategically to contain, suppress, and ideally to eradicate the target disease. By promoting innovations and their diffusion together, the HIF would greatly increase the cost-effectiveness of the pharmaceutical sector, benefiting the world’s poor especially

By Thomas Pogge

Leitner Professor of Philosophy and International Affairs

Yale University, New Haven, USA

Equitable Access to Innovative Pharmaceuticals

Background

Equitable access to health requires equitable access to health care. In our world, such equitable access does not exist because billions of human beings are denied a minimally adequate income and also because patented pharmaceuticals are absurdly overpriced.

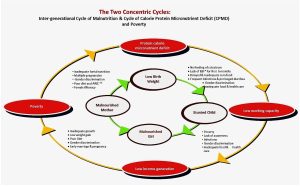

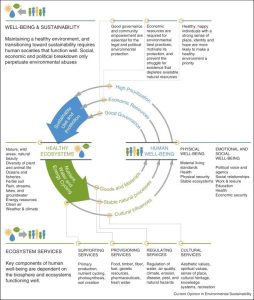

According to the latest FAO Report, three billion human beings – 41.9% of humankind – were unable, in 2019, to afford a healthy diet at an average cost of USD 4.04 per person per day at purchasing power parity[1] – even while the global average income (also purchasing-power-adjusted) was about USD 50 per person per day.[2] Being so desperately poor, large percentages of humankind also lack safe drinking water,[3] adequate sanitation,[4] adequate shelter,[5] electricity[6] and basic education.[7] These severe deprivations make the poor much more prone to disease which in turn further reinforces their poverty. The grave injustice of these deprivations is apparent from the fact that they would not exist if poor people merely had their fair per capita share from the human exploitation of natural resources: minerals extracted, and planetary commons depreciated by human pollution. As it is, this natural wealth of our planet is unilaterally used and overused by a minority of humankind without compensation to the rest, while the poor must work very hard for their insufficient incomes.

The Monopoly Patent Regime

This severe injustice is further aggravated by the existing international rules governing innovation which, originating in the most affluent states, were foisted upon the rest of the world through the 1995 TRIPs Agreement, part of the WTO founding treaty.[8] These rules entitle innovators to 20-year product patents whose exclusivity provisions enable patentees to collect monopoly rents from early users.[9] Monopoly markups encourage development of innovations, but at the cost of greatly impeding their diffusion. This cost again falls most heavily upon the poor, who are excluded from advanced medicines during their patent period.

Monopoly patents lead to exorbitant prices, especially in the pharmaceutical sector. A typical example is sofosbuvir, an effective cure for hepatitis C, which Gilead Sciences introduced in the United States in 2013 under the brand name Sovaldi at a price of USD 84,000 per course of treatment. This is about 3000 times the cost of manufacture, a markup of 300,000%.[10] In poorer countries, where the upper classes are less affluent and less well-insured, patented drugs are priced much lower – but still unaffordable on the also much lower ordinary incomes there. Even five years after sofosbuvir’s market introduction, only about 7% of the 71 million persons living with hepatitis C had been treated, while the remaining 66 million remained ill and potentially infectious to others.[11] Such disease proliferation benefits the patentee who, by deploying its new drug in a global population-level strategy of disease eradication, would be reducing its current earnings and undermining its future sales.

Prices for advanced pharmaceuticals are set at such exorbitant levels because this is the most lucrative choice. Because economic inequalities are very large, even intra-nationally,[12] it is profit-maximizing to aim an important product at the affluent and well-insured: a lower price would not gain enough in increased sales volume to compensate for the loss in reduced profit margin. Each year, hundreds of millions suffer, and millions die, from lack of access to medicines that generic firms could and would supply quite cheaply if patent enforcement did not prevent them from doing so.[13]

Making pharmaceutical firms reliant on monopoly rents hurts the world’s poor also through its influence on R&D decisions. Firms that derive their earnings from monopoly markups ignore diseases that are heavily concentrated among the poor, as is shown by the strong correlation between disease-specific R&D investments and the average income of the corresponding patient population.[14] As a result, while male pattern baldness and erectile dysfunction garner abundant research attention, humanity is woefully underequipped with pharmaceuticals against the 20 WHO-listed “neglected tropical diseases,” which “cause devastating health, social and economic consequences to more than one billion people,”[15] as well as the familiar great diseases of poverty – including tuberculosis, malaria, hepatitis, pneumonia, and diarrhea – which routinely kill some six million people every year.[16]

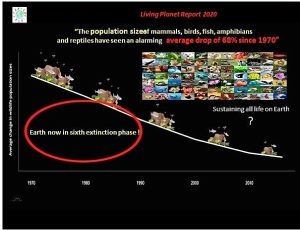

Systematic neglect of the poor in both R&D and distribution of pharmaceuticals allows them to be a breeding ground where new diseases, such as Ebola, swine flu, and COVID-19, can gain traction and old diseases can survive and evolve new, perhaps more virulent or drug-resistant disease strains – as has happened with tuberculosis in China and India, and with malaria in South East Asia and Ethiopia. In this regard, the interests of poor and rich are well-aligned: we all want to see diseases contained, suppressed, and eradicated from this planet. But the only way to achieve this is with a population-level strategy that includes the poor.

Humanity has eradicated only one human disease, smallpox, in a joint effort led by the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War.[17] We certainly could have eradicated other infectious diseases too, including most of those mentioned two paragraphs back. But under the current innovation regime, disease eradications are unlikely.[18] Here is why. Pharmaceuticals can protect people against harm from infectious diseases in two distinct ways. At the individual level, they can protect their users. At the population level, they can be deployed to contain and suppress a disease toward eradication, thereby saving people from being endangered by it in the first place. Although we consumers much prefer being benefited in the latter way, this way is money-losing for pharmaceutical firms which profit only by benefiting people in the former way. It is not profitable for them to address the needs of poor patients; and it is financial suicide for such a firm to suppress a disease for which it is selling an exclusive remedy. Under the current monopoly patent regime, pharmaceutical firms have a vital financial interest in the continued flourishing of their target disease. Thanks to this interest, the poor – though unable to afford patented medicines – nonetheless make a crucial indirect contribution to innovator profits.

To summarize and generalize. By relying on temporary monopolies, our current regime for stimulating and rewarding innovation generates two interrelated and highly destructive problems. It fails to realize huge potential benefits for poor people by guiding innovators to ignore their specific needs and to price existing innovations out of their reach. Relatedly, it fails to reward and hence to induce vast third-party benefits that a technology’s buyers and users care little about. The pharmaceutical sector illustrates both problems to perfection.

A Supplementary Health Impact Fund

Earning trillions of dollars on their patents each year,[19] patentees are willing and able to defend their privileges ferociously. The chances of achieving meaningful revisions of the TRIPS regime are therefore slim or nil. Twenty-five years of attempts at the WHO have yielded next to nothing; and the latest episode – the proposed TRIPS waiver for COVID-related products – has similarly been mired in shameful stalling and delay with daily reductions in the good it might yet accomplish. It is high time to explore the politically more realistic approach of addressing the problems without revision of the TRIPS framework.

The most important objective here is to incentivize firms to fully include poor people in their business strategy. Such inclusion requires an effective new pharmaceutical to be cheap enough to be affordable to all while delivering it to even the poorest is profitable enough for firms to want to do so comprehensively and effectively. In our world of widespread poverty, these two requirements stand in tension. There is no sales price that is low enough to fulfill the former and high enough to fulfill the latter requirement. To resolve this tension, firms must receive a delivery premium in addition to the sales price.

This can be achieved by creating a sector-specific add-on to the current regime: an international Health Impact Fund (HIF) that invites innovators to permanently forgo monopoly markups on a new patentable pharmaceutical in exchange for impact rewards. The word “invites” is key: innovators would have a choice, in regard to each qualifying innovation, whether or not to register it with the HIF.

The prohibition on monopoly markups could be implemented through open licensing or, perhaps preferably, through a tender process that selects two or three reliable contract manufacturers to mass-produce the registered pharmaceutical on the registrant’s behalf to meet global demand. Such a tender process affords superior economies of scale, facilitates health impact measurement, and makes it easy for the registrant to sell the product below its price cap into impoverished regions when the expected additional health gains make it profitable to do so.[20]

The HIF would pay registrants of a new pharmaceutical an alternative reward based on the incremental health gains produced with it. Here “health gains” are defined to include externalities, such as the benefits that use of a HIF-registered product confers upon third parties in the form of reduced infection risk. A registered pharmaceutical would earn its maximum reward by eradicating its target disease – and this even if the innovator then had no more patients left to treat with it.

Under the current monopoly regime, new pharmaceuticals that are just slightly better than existing alternatives can earn as much as first-in-class innovations; and duplicative products that do not improve the state of the art at all can still capture a large market share, thereby garnering huge profits and reducing the rewards of a preceding break-through innovation. The HIF avoids such inefficiencies by rewarding only incremental health gains, gains that would not have occurred without the registered innovation. It thereby discourages socially wasteful efforts to field a duplicative product against a HIF-registered innovation: if HIF-registered, the duplicate would earn too little for lack of incremental impact; if unregistered, it would earn too little because of its uncompetitive price.

The HIF would pay its rewards through fixed annual disbursements, each split among registered pharmaceuticals according to incremental health gains achieved in the preceding year. This principle of division ensures fairness among innovators, who are rewarded in proportion to benefit provided, all at the same reward-to-benefit rate. Each innovation would participate in ten of these annual disbursements and be freely available thereafter through open licensing.

So designed, the HIF would evolve a stable competitive reward rate. When innovators find it unattractive, registrations slow and the reward rate rises as older innovations exit at the end of their reward period. When the rate is seen as generous, it soon declines through proliferating registrations. Such predictable adjustment reassures registrants and funders alike that the reward rate is fair, and will continue to be fair, between them. By design, innovations earn competitive rewards.

The size of the annual disbursements can be set, and possibly raised, to attain the desired level of participation. If the HIF had annual disbursements of €6 billion, each registered pharmaceutical would participate in €60 billion worth of disbursements over its ten-year reward period. A commercial innovator would register a product only if it expected to make a profit over and above recouping its R&D expenses. There is some controversy over what these fixed costs per innovation (inflated to account for the risk of failure) amount to. The number of products registered with the HIF would throw light on this question because of the Fund’s self-adjusting reward rate. Were it to attract, say, 30 products, with three entering and three exiting in a typical year, this would show that the prospect of €2 billion over ten years is seen as satisfactory – neither windfall nor hardship.

The HIF improves upon innovation prizes and other pull mechanisms, such as advance market commitments,[21] in five ways. It constitutes a structural reform, establishing stable and predictable long-term innovation incentives. It lets innovators, who know their own capabilities best, decide which innovations to pursue across the whole range of disease areas. It avoids having to specify a precise “finish line” – hard to get right in advance – and instead rewards each registered innovation according to the benefits produced with its deployments. It avoids having to specify a reward-for-benefit rate, which instead evolves endogenously through market forces. It gives innovators strong incentives also to promote (through information, training, technical assistance, discounts, etc.) the fast, wide, impactful diffusion of their participating innovations.

The HIF would quite easily offset its cost through lower prices on registered pharmaceuticals and through large reductions in the global burden of disease, entailing cost-savings in other health care costs as well as substantial gains in economic productivity and associated tax revenues. Nevertheless, these great potential benefits must be appreciated, and this appreciation be converted into reliable long-term funding commitments. Innovators considering a high-impact R&D project must have firm assurance that they will get paid during their product’s first ten years on the market. If HIF rewards are perceived as uncertain, innovators will discount them with the result that its reward rate will be higher than necessary.

At least initially, reliable long-term commitments will have to be underwritten by states, with optionality again important for political feasibility. The HIF can get started with a few states, even just one. It makes sense to design the HIF so that it lets participating innovators sell their registered pharmaceuticals at patent-protected high prices in non-contributing affluent countries. This exception would give affluent countries a further incentive to join the funding partnership. It would also reduce the opportunity cost of HIF-registration, thereby raising the number of products the HIF would attract at a given size of annual disbursements.

With state contributions based on gross national income, the HIF might expand over time – through economic growth in contributing states, accession of new states, or agreement to raise the contribution rate – and would then attract more registrations. Similar growth could occur if states decided to devote part of an international tax – on greenhouse gas emissions, perhaps, or on financial transactions – to the HIF. In any case, the HIF should also welcome donations from non-state actors (foundations, corporations, individuals, and bequests), perhaps using them to build an endowment that could support an increasing share of its annual budget.

Most of the HIF’s cost would be borne by more affluent countries and people. The same is true of monopoly rents extracted from early buyers. But there is this crucial difference: impact rewards avoid excluding the poor. Such exclusion is deeply immoral, as when millions die from lack of medicines that generic manufacturers would be glad to supply quite cheaply. Such exclusion also harms us all by exposing us to dangers from diseases that emerge or propagate among the poor, often evolving new variants – or drug resistance, emerging when patients cannot afford to take the full dosage or full treatment course of an expensive drug.

Organizing a wide competition across the entire pharmaceutical sector, the HIF would create a new kind of competitive market that helps innovations achieve their full potential. Removing the headwind of monopoly rents and adding a tailwind of impact rewards, such a market transforms innovator motivation. While monopoly rewards incite massive efforts to deter, detect and terminate patent infringements, the HIF would encourage participating innovators actively to promote – through local-language instructions, adherence support, discounts, training, technical assistance, diagnostics, etc. – the rapid, widespread, and effective deployment of their technology for optimal benefit. It would stimulate innovators to holistically organize their research, development, marketing, and delivery operations toward producing the most cost-effective incremental health gains. In this way, the HIF would induce the development of precisely those high-value innovations that the current regime leaves inadequately rewarded. Innovators would have financial incentives to supply these new HIF-registered pharmaceuticals at very low prices and to collaborate with their large customers – national health services and organizations like the Global Fund, GAVI, Médecins Sans Frontières, and Partners in Health – on the optimal strategic deployment of these products aimed at containment, suppression, and ultimately eradication of the target disease. Creation of the HIF would greatly improve the prospects of permanently freeing humanity from some of the most destructive infectious diseases and greatly enhance humanity’s capacities to tackle new infectious diseases and disease strains.

A Health Impact Fund Pilot

The example of the Global Fund suggests that creation of the HIF is entirely possible. To mobilize the needed political support, it would be extremely helpful to try out the HIF approach on a smaller scale. COVID-19 was a great opportunity to do so. Instead, this pandemic became a depressing showcase for the flaws of the current monopoly regime. Effective vaccines were developed in record time. But manufacturing was scaled up slowly as innovators sought to safeguard their proprietary technologies and know-how, to avoid wasteful excess capacity, and to maintain a favorable demand-supply imbalance conducive to high prices. And the distribution of vaccines was driven not by a strategic effort to suppress the disease but by a scramble to maximize monopoly rents: innovators prioritized buyers who offered to pay more and rejected those who, only marginally profitable, might erode the product price and seemed more useful spreading and prolonging the pandemic with potential emergence of new disease variants.

Fortunately, a suitable HIF pilot is always feasible. Featuring a single reward pool of ca. €100 million, such a pilot might invite innovators to submit proposals of how they might, with one of their existing pharmaceuticals, achieve additional health gains in some selected poor country or region. An expert committee would select the four best proposals based on, inter alia, anticipated incremental health gains, prospects for broad, equitable access especially by the poor, susceptibility to reliable, consistent, and inexpensive health impact assessment, and promise of additional social value. Selected proponents – which might include non-commercial innovators such as DNDi and the TB Alliance – might then have three years for implementation. Thereafter, achieved health gains would be assessed – according to pre-agreed criteria, by an agency like the IQWIG, DEval or IHME – and the reward pool be divided proportionately.[22] The pilot would show how innovators respond to the novel competitive impact rewards, would help refine impact assessment, and would indicate how well impact rewards work in generating health gains and supplementary health policy insights. The most important objective here is to incentivize firms to fully include poor people in their strategy right from the start. For this to happen, an effective new pharmaceutical must be cheap enough to be affordable to all while delivering it even to the poorest must be profitable enough for firms to be eager to do so comprehensively and effectively. In our world of widespread poverty, these two requirements stand in tension. There is no sales price that is low enough to fulfill the former and high enough to fulfill the latter requirement. To resolve this tension, firms must receive a delivery premium in addition to the sales price. Such a premium, tied to health gain achieved, is an essential component of the Health Impact Fund approach, which offers firms performance rewards based on the real health gains they achieve with any of their products, on condition that they sell this product without markup (HealthImpactFund.org, 2021).

Conclusion

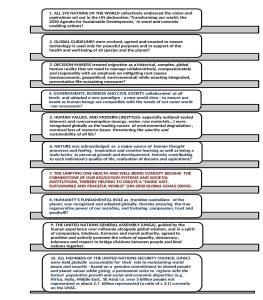

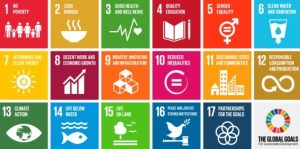

By supporting establishment of the HIF, citizens and governments of contributing states could take a real step toward fulfilling their long-declared commitments to human rights, poverty eradication, the 2030 Agenda of Sustainable Development Goals, and an international spirit of planetary solidarity.

The current global innovation regime perpetuates staggering global health deficits. Creation of the HIF is an extremely cost-effective reform that could avert most of this harm – potentially freeing millions of poor people from their debilitating ailments and greatly raising humanity’s preparedness against communicable diseases. In fact, the HIF’s true cost is likely to be negative insofar as savings on registered pharmaceuticals and other health-care costs as well as gains in economic productivity and associated tax revenues would benefit the contributing funders – also indirectly by reducing the cost of health insurance, national health systems, and foreign aid. Further economies would arise from the HIF largely avoiding the wasteful expenditures now typical of the pharmaceutical sector: expenses for multiple staggered patenting in many jurisdictions with associated gaming efforts (e.g., evergreening), costs of preventing monopoly infringements, costs of duplicative innovations with mutually-offsetting competitive promotion efforts, economic deadweight losses, and costs due to corrupt marketing practices and counterfeiting. Thanks to these enormous inefficiencies of monopoly incentives, a shift toward impact rewards could dramatically improve global health and the lives of the poor without cost to anyone. Pharmaceuticals firms, in particular, would gain wholly new opportunities to do well by doing good: to earn money by benefiting rather than harming poor populations. Aligning profits with human needs, the HIF would make the business of innovation much more equitable in terms of research priorities and access to its fruits.

Endnotes

[1] FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021 (Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2021), https://doi.org/10.4060/cb4474en, Table 5, p. 27. Since 2019, the situation has become even much worse, as the crises of climate, COVID-19, and Ukraine have caused a unprecedented 68% surge in food prices, driving the FAO’s food price index from 95.1 in 2019 to 159.3 in March 2022 (https://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/foodpricesindex/en/).

[2] https://www.givingwhatwecan.org/post/2021/03/measuring-global-inequality-median-income-gdp-per-capita-and-the-gini-index/

[3] 2.2 billion human beings lack safe drinking water, http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drinking-water

[4] 2 billion people live without adequate sanitation, https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sanitation

[5] Well over 1 billion people lack adequate housing. UN Habitat, Fact Sheet 21: The Right to Adequate Housing, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Publications/FS21_rev_1_Housing_en.pdf , p. 1.

[6] 940 million people have no electricity, https://ourworldindata.org/energy-access

[7] Some 160 million children aged 5–17 do wage work outside their own household and hence do not go to school (https://www.ilo.org/ipec/Informationresources/WCMS_800278/lang–en/index.htm) and over 750 million adults are illiterate (https://en.unesco.org/themes/literacy).

[8] John Braithwaite and Peter Drahos, Global Business Regulation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), esp. chapters 7, 10, 20, 21. Daniel Gervais, The TRIPS Agreement: Negotiating History, Fourth Edition (London: Sweet & Maxwell, 2012).

[9] TRIPS Agreement, https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/trips_e.htm, Articles 27, 28 and 33.

[10] Melissa J. Barber, Dzintars Gotham, Giten Khwairakpam, and Andrew Hill, “Price of a Hepatitis C cure: Cost of Production and Current Prices for Direct-Acting Antivirals in 50 Countries,” Journal of Virus Eradication 6, no. 3 (2020): 100001. Available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jve.2020.06.001

[11] Clinton Health Access Initiative, “Hepatitis C Market Report, Issue 1” (2020), p. 10. Available at https://www.globalhep.org/sites/default/files/content/resource/files/2020-05/Hepatitis-C-Market-Report_Issue-1_Web.pdf

[12] Sean Flynn, Aidan Hollis, and Mike Palmedo, “An Economic Justification for Open Access to Essential Medicine Patents in Developing Countries,” Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 37, no. 2 (2009), 184–208 at pp. 187–188.

[13] Arguably, cutting patients off from affordable access to life-saving drugs in this way constitutes a violation of their human rights. See Thomas Pogge, “The Health Impact Fund and Its Justification by Appeal to Human Rights.” Journal of Social Philosophy 40, no. 4 (2009), 542–569. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-9833.2009.01470.x/abstract.

[14] Javad Moradpour and Aidan Hollis, “Patient Income and Health Innovation,” Health Economics Letter (2020). Available at https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.4160.

[15] See World Health Organization, “Neglected Tropical Diseases,” https://www.who.int/health-topics/neglected-tropical-diseases#tab=tab_1.

[16] Our World in Data reports 2.56 million deaths from pneumonia in 2017 (https://ourworldindata.org/pneumonia), 1.53 million deaths from diarrheal diseases in 2019 (https://ourworldindata.org/causes-of-death), 1.18 million deaths from tuberculosis in 2019 (https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/tuberculosis-deaths?tab=chart&country=~OWID_WRL), 627,000 deaths from malaria in 2020 (https://ourworldindata.org/malaria) and 79,000 deaths from hepatitis in 2019 (https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/deaths-from-acute-hepatitis-by-cause).

[17] Frank Fenner, Donald Henderson, Isao Arita, Zdenek Jezek, and Ivan Danilovich Ladnyi. Smallpox and its Eradication (Geneva: World Health Organization 1988). https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/39485.

[18] To be sure, non-commercial innovators occasionally obtain funds to work on such diseases, leading to successes like the recent malaria vaccine developed at Oxford University: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/apr/25/new-vaccine-success-for-oxford-is-truly-remarkable. But they rarely have enough money for a successful tripartite campaign of product development, large-scale product manufacture, and global product distribution.

[19] In the pharmaceutical sector alone, sales of brand name products amount to about $800 billion annually. See International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations, “The Pharmaceutical Industry and Global Health” (2017), p. 5, https://www.ifpma.org/resource-centre/ifpma-facts-and-figures-report

[20] For more detailed discussion, see Thomas Pogge, “The Health Impact Fund: Enhancing Justice and Efficiency in Global Health,” in Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 13, no. 4 (2012), 537–559 at pp. 550–552.

[21] See Michael Kremer and Rachel Glennerster. Strong Medicine: Creating Incentives for Pharmaceutical Research on Neglected Diseases (Princeton: Princeton University 2004); and Michael Kremer, Jonathan Levin, and Christopher M. Snyder. “Designing Advance Market Commitments for New Vaccines” (2020). Online at https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/kremer/files/amc_design_36.pdf.

[22] Sophisticated methods of health technology assessment exist and are widely used, especially by national and private insurers, so the HIF and its pilot could draw on these methods.