In the current pandemic scenario, public health experts need to look at the establishment of animal health care and the strengthening of an ecosystem where human and animal will live congruently to protect human health. This integrated, holistic and harmonious approach to protecting human health is referred to as one world one health, a name coined by the wildlife conservation society. A better understanding of the ecosystem is needed to protect public health

By Dr. Meenakumari Natarajan, MPH.Ph.D

Health Economist, Epidemiologist

Scientist-C-National Institute of Epidemiology (NIE-ICMR), Chennai – India

Back to Basics

Lessons Learnt from COVID-19 Pandemic

In this postmodern world, matching pace with the world’s growth and securing a place for oneself, our complicated life is burdened with the fear of new, sometimes anonymous diseases which are growing drastically, and it is a major concern for research. One such disease is COVID-19. The world is becoming small, national borders are diminishing by recent developments in all sectors. More people travel or trade across the global. Our ecosystem also includes forest, sea and space. With all these changes it is becoming easier for diseases have jumped from animals to human.

The viruses find ways to jump from species to species. Jumping from one species to species is a good survival strategy for viruses like swine flu virus, HIV, now coronavirus. COVID-19 is a relatively new virus. It has only recently jumped to human which is part of the reason. Viruses need hosts and that jumping among hosts is good for viruses but often not so good for hosts. In recent days scientists have made amazing and wonderful progress in tracing the origin of COVID-19: found bats were indeed involved. (Kock, Karesh et al. 2020)

At present mankind is facing many challenges, which will require globally integrated solutions. The spread of infectious diseases that jumped from animals to human was mainly by the interface in the ecosystem which they live. In the preindustrial phase, birth and death rate were similar, the world was balanced fluctuated conferring to natural events like droughts and disease. Unfortunately, the invention of new techniques and procedures caused the death rate to decline further resulting in a population explosion. Millions of animals were hunted to feed billions of people. It is important to note, that the present evidence that exponential growth of population, urbanization, modernization of the farming system all made encroachment of forest and closer interaction of wildlife thereby exposing humans and domestic animals to new pathogens.

In this scenario, public health experts need to look at the establishment of animal health care and the strengthening of an ecosystem where human and animal will live congruently to protect human health. This integrated, holistic and harmonious approach to protecting human health is referred to as one world one health, a name coined by the wildlife conservation society. A better understanding of the ecosystem is needed to protect public health.

World history is plagued with wars, boycotts, violence, and pandemics; however, death and health are shaken by uncontrolled pandemics such as COVID-19. Many countries have done enormous effort to contain COVID-19 such as early diagnosis, contact tracing, contact isolation, quarantine, social distancing, temporary hospital construction, financial support to citizens, closing the national borders, cutting off transportation intra and international etc.. This increases many additional issues such as global economic loss, Economic recession, economic slowdown and supply chain cut off. At present we do not have any clear-cut structure or strategy to confront a future global pandemic and economic crisis. (Pan, Ojcius et al. 2020).

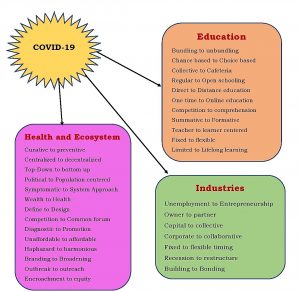

Now the world is moving towards health promotion, disease prevention and it cannot be achieved by alone. It requires support from other sectors such as education, agriculture, industries etc. It requires cooperation and partnership across the disciplines. It is time for the world to review their pandemic plans to address pandemic preparedness in their business plans Many countries have started, tested and updated their plans to reduce the negative impact of a pandemic on the industry, economy, education, ecosystem and health. (Chakraborty and Maity 2020)

However, in line with the ideas of harmonious life with the ecosystem, it can be concluded that this is time for us to Revisit, Revise, Restructure, Reform, and Rebuild ourselves to counteract future crisis.

References

- Chakraborty, I. and P. Maity (2020). “COVID-19 outbreak: Migration, effects on society, global environment and prevention.” Sci Total Environ 728: 138882.

- Kock, R. A., W. B. Karesh, F. Veas, T. P. Velavan, D. Simons, L. E. G. Mboera, O. Dar, L. B. Arruda and A. Zumla (2020). “2019-nCoV in context: lessons learned?” Lancet Planet Health 4(3): e87-e88.

- Pan, X., D. M. Ojcius, T. Gao, Z. Li, C. Pan and C. Pan (2020). “Lessons learned from the 2019-nCoV epidemic on prevention of future infectious diseases.” Microbes Infect 22(2): 86-91.