This literature review aims to identify evidence-based built environment interventions that may be deployed in North American contexts to mitigate and adapt to the health effects of climate change. Identified mitigation and adaptation strategies are then analyzed for potential application within a suburban context

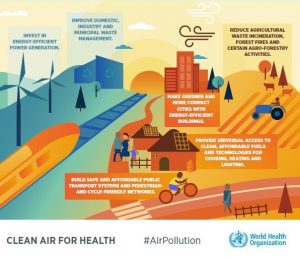

image credit: WHO

Debbie Brace1, Vanessa Kishimoto2, Michelle A. Quaye3, Mike Benusic4, Louise Aubin5, Lawrence C. Loh, MD, MPH, FCFP, FRCPC, FACPM4,5

1 – Degroote School of Medicine, McMaster University

2 – Faculty of Arts & Science, University of Toronto

3 – Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University

4 – Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto

5 – Region of Peel—Public Health

Mitigating and Adapting to the Effects of Climate Change on Health in the Suburbs Through Adaptations in the Built Environment

A Literature Review

Background

Climate change has been heralded as the “biggest global health threat of the 21st century” (Watts 2018). The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that between 2030 and 2050, climate change will cause 250 000 deaths per year: 38 000 due to heat exposure in elderly people, 48 000 due to diarrheal diseases, 60 000 due to malaria, and 95 000 due to childhood under-nutrition (World Health Organization 2018).

One way of categorizing the health impacts of climate change is classifying those impacts as direct or indirect. Examples of direct health impacts include worsening air pollution that can contribute to cardiovascular diseases or heat stress and injuries due to more extreme weather, while indirect effects include food insecurity due to extreme weather and droughts, or changes in vector patterns that contribute to higher rates of vector-borne diseases (Watts 2018).

Another categorization from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) categorizes health effects as they relate to environmental changes such as rising temperature, extreme weather, rising sea levels, and increasing carbon dioxide levels (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2014).

There is also a recognition that different communities and populations will be impacted by these health effects. Well known are the anticipated impacts on vulnerable populations of concern including the elderly, young children, individuals living with chronic diseases, and individuals of lower socioeconomic status or social marginalization. (Buse 2012, Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change 2018) However, there will also be differential impacts anticipated by community context and form, with suburban settings being of particular importance given that they are home to a large proportion of the Canadian population.

Suburbs face the highest growth in the coming years (Ibbitson 2018) while simultaneously presenting challenges to climate change intervention owing to their automobile centric design and lower population density (Williams et al. 2010, 2012). Given this, our literature review aims to identify evidence-based built environment interventions that may be deployed to mitigate and adapt to the health effects of climate change. Identified mitigation and adaptation strategies are then analyzed for potential application within a suburban context.

Context

Suburbs represented the predominant planning paradigm following World War II, driving increasing sprawl and automobile-dependence in metropolitan areas across Canada. (David and Janzen 2013). Suburbs have become the predominant neighbourhood type for metropolitan dwellers, with the Canadian suburban population surpassing the city centre population in the 1970s (Bourne 1996). By 2006, 80% of Canadians in metropolitan areas lived in suburbs (David and Janzen 2013). It has been estimated that two thirds of the total Canadian population live in suburbs. Gordon and Shirokoff (2014) found that the overwhelming majority of population growth in a study of census metropolitan areas was found to be in automobile-dependent suburbs and “exurbs”, defined as rural areas with commuting access to metropolitan centres. Suburbs are currently growing 160% faster than city centres in Canada (Thompson 2013).

The typical North American suburban community has a built form that encompasses low density housing, dispersed amenities and services, and reliance on personal vehicles (Leichenko and Solecki 2013). Despite these common elements, various suburbs exhibit demographic differences with regards to age, income, and visible minorities, with consequent impacts on health status. As an example, while suburbs have traditionally resulted in housing that is more affordable compared to the city, low socioeconomic status individuals living in suburbs often find themselves isolated from easy geographic access to work and important services because of unaffordability of automobiles and poor public transit infrastructure (Bourne 1996).

Community reliance on automobile transport also affects environmental health and drives climate change through air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions (Gordon and Shirokoff 2014). Greenhouse gas emissions come largely from road-based vehicles, and these emissions increased 33% from 1990 to 2010. Motor vehicles are also sources of air contaminants that lead to smog, with smog estimated to be responsible for 9500 deaths in Ontario per year.

Finally, other climate change effects experienced differently by suburban settings are extreme weather events, which can cause community and economic disruption (Thompson 2013), and also extreme temperature events, particularly extreme heat, which amplify the urban heat island effect. The latter is the result of infrastructure supporting suburban reliance on motorized vehicles (i.e. wide roadways and highways, industrial surfaces, a lack of vegetation, and parking lots) which results in surface temperatures that magnify the urban heat island effect in suburban areas (Taylor et al. 2018).

An example of a suburban community is the Region of Peel, a diverse and large upper-tier municipality in the Greater Toronto Area that is home to nearly 1.3 million people (Region of Peel 2016). Peel encompasses three municipalities, the Town of Caledon, and the cities of Mississauga and Brampton, and has a predominantly suburban form that envelopes dense urban, urbanizing, and rural forms. Approximately 14.7% of the population of Mississauga, 11.3% of Brampton and 5.7% of Caledon are considered low income (Region of Peel 2017a). According to the 2016 census, 62.3% of the Peel population are a visible minority, of whom 50.8% are South Asian, 15.3% are African American and 7.5% are Chinese (Region of Peel 2017b).

Concerning the urban heat island effect, meteorological data has demonstrated that Peel has seen an average increase in daily temperature of 1.2°C between 1938 and 2017 (Region of Peel 2019), though the range of surface temperatures varies, particularly with distance from the lake. Data on vegetation shows that 11% of Brampton, 15% of Mississauga, and 29% of Caledon East has tree cover (Buse 2012), with no recorded data for tree cover in Caledon West.

This context and community example shows the importance of intervening to address the impacts of climate change for all who live in suburban settings, while also prioritizing vulnerable populations that already experience disadvantage and are at increased risk of adverse health outcomes.

Methods

A literature review was performed to identify current built environment interventions being used to mitigate and adapt the health effects of climate change that may apply to a suburban context. The following databases were searched: Environment Complete, Web of Science, PsychINFO, Emcare, PubMed, MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process, Global Health, Health Star, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Search terms used were: climate change, global warming, environmental pollution and/or greenhouse effect, and health, and measuring, mitigating, strategies, interventions, policy or prevention, and/or city planning or environmental design or built environment. The search was limited to papers published in English, between 2009-2019, and available online.

The initial search provided 577 results. A single reviewer scanned titles and abstracts to determine inclusion or exclusion based on their relevance to climate change and health, and interventions specifically relating to the built environment. Papers were included if they cited climate change as the exposure of interest, analyzed the effect of an intervention in the built environment, reported human health-related outcomes, and were published in English. Papers were excluded if they could not be applied to North American contexts (i.e., if the papers were based in a low-income or developing nation), if they were published before 2009, and if they were not related to suburban environments. A total of 23 articles were identified as possible for inclusion. One was excluded as it was not available in online archives. A further 9 were excluded as they did not report health outcomes related to climate change, or were related exclusively to urban contexts. Two reviewers then retrieved these articles and appraised these full texts for final inclusion. In total, 13 articles met the criteria.

From these included articles, promising built environment interventions were then extracted and summarized in key themes, which underwent critical analysis. These themes were then critically analyzed against suburban context and considerations to identify interventions that might support adaptation and mitigation efforts in such settings.

For the purposes of this review, we defined mitigation interventions as those designed to abate contributing factors to climate change, with related health co-benefits, and defined adaptation measures as adjusting and resourcing a community to manage health-related climate change impacts (Prior et al. 2018).

Results

Thirteen papers were identified in our review. Six articles were literature reviews and five articles reported simulation or predictive modeling. The final two papers were primary research articles, one of which was an online survey of Australian’s heat stress resilience, while the other reported on water quality monitoring and interventions.

Identified common themes for suburban interventions included urban vegetation and green infrastructure to cool temperatures, reducing heat stress, improving infrastructure resiliency, retrofitting buildings, and reducing greenhouse gases by promoting healthy and active living.

Mitigation

Two articles found that active transport was linked with better health outcomes and decreased greenhouse gas emissions (Ulmer et al. 2014, Frank et al. 2010).

Ulmer et al. (2014) used predictive modeling to characterize the health impacts of policies and laws regarding urban planning, land use and transportation. They found that walkability, sidewalks, bike facilities, and recreational activities was correlated with more physical activity and better health, as well as decreased greenhouse gas emissions.

Frank et al. (2010) used simulations to investigate how active transport can improve health and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. They found that increasing transit and density improves health indicators and decreases emissions from motorized transport and concluded that funding for transit should be increased to improve health and climate sustainability.

Adaptation

Five of the papers investigated the impact of green infrastructure, such as urban vegetation, green roofs, and suspended pavements to protect vegetation. Taken together, these papers found that green infrastructure reduces the risks of climate-related exposures. Stone et al. (2013) demonstrated that increased vegetation in urban centres and the surrounding areas was linked with mitigation of the “urban heat island effect” through decreased land surface temperature. Several other papers also linked vegetation to improved air quality and reduced pollutant concentrations, which was predicted to help mitigate anticipated poorer air quality owing to hotter ambient community temperatures (Abhijith et al. 2017, Page et al. 2015, Demuzere et al. 2014, Houghton and Castillo-Salgado 2017).

Four articles demonstrated that various building retrofits could reduce heat related mortality; three of these were specific to residential buildings (Taylor et al. 2018, Hatvani-Kovacs et al. 2016, Williams et al 2013) while one was a general review of cooling technologies (Pisello 2017). Of note, Taylor et al. (2018) found that shutters on windows were linked with lower summer time heat-related mortality, while complete energy-efficient retrofitting was associated with an increase in heat-related mortality. This finding was at odds with the other three papers that linked energy efficient retrofitting and cool coatings with decreased risk of heat-related illness and better health outcomes (Hatvani-Kovacs et al. 2016, Williams et al. 2013, Pisello 2017).

Two of the papers were literature reviews investigating the various strategies and characteristics being used to mitigate urban heat islands (Santamouris et al. 2017, Hintz et al. 2017). Both of these papers identified benefits from a multifactorial approach including the use of urban vegetation and green infrastructure, the use of cooling techniques like increased albedo on surfaces, and individual behaviors, such as remaining in air conditioned spaces and avoiding strenuous exercise during extreme heat events (Santamouris et al. 2017, Hintz et al. 2017).

Discussion

Our review found evidence-based interventions that, if implemented, could have promise in addressing climate change contributions and impacts in suburban settings. Both mitigation and health-protective adaptation efforts would be supported by suburban investments in green infrastructure, the former through improved carbon capture by increased foliage and shade, and the latter through increased soil and root systems that increase resilience to seasonal flooding and improved air and water quality. Other interventions that could be deployed in suburbs to protect health relate more to adaptation, specifically building retrofits that might reduce heat-related mortality and morbidity, and health promotion messaging that encourages remaining indoors and avoiding strenuous physical activity during extreme heat events.

Broadly applying these interventions to the suburban context, one notes that active transportation (e.g., walking, cycling, taking public transit) would not only contribute to climate change mitigation efforts but also provide important health co-benefits through increased physical activity and improved air quality. In the absence of built environments that encourage physical activity, it has been shown that there is risk of obesity (Papas et al. 2007). In addition, increased driving time has been associated with higher prevalence of self-reported smoking, physical activity, insufficient sleep and psychological distress (Ding et al 2014). In other parts of the world, childhood asthma has emerged, likely as a consequence of industrial and car-related pollution (Loh and Brieger 2014)

People who live in suburbs spend more time in cars, owing to long distances, low density, and limited public transport. (Sugiyama et al. 2012). Active transportation use in adults is further associated with subjective density, mixed land use, walkability, and safety for cycling (Van Dyck et al. 2013). However, our findings are clear that a suburban transformation toward active transportation is not optional; in addition to mitigating climate change, greater intensification to promote active transportation will provide health benefits to a growing population and reduce congestion and air pollution. Compared to traditional urban settings, suburban contexts will require significant investment and effort in determining how to transform automobile-focused transportation infrastructure towards making active transportation safer, more desirable, and more feasible in thinking of where and how people move around.

This review also found that green infrastructure and urban vegetation has important mitigation and adaptation benefits. In the Region of Peel, substantial natural cover is present largely in the northern rural areas, with more built up areas in the south left vulnerable to urban heat island effect. Research suggests that areas vulnerable to urban heat island effect would benefit from increased urban vegetation and green infrastructure, which is linked to lower land surface temperatures, better air quality, and flood mitigation. This poses considerable challenges given the spread and scale of various developments that rely on wide arterial roads and low-density buildings with extensive parking lot facilities.

The final theme that emerged from the literature is that of building retrofitting, though evidence in this review is mixed. Increasing the energy efficiency of buildings through retrofitting would help reduce energy use and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, while helping residents adapt to extreme shifts in temperature. Specific data from Natural Resources Canada indicate that residential and commercial activities account for about 14% of total Canadian energy use and greenhouse gas emissions; in residential settings, data suggests that 81% of the energy consumption is used for space and water heating (Natural Resources Canada 2019). As most retrofits are cost-effective when borne out in more dense settings, suburban settings will need to consider how best to encourage changes, particularly in residential settings.

Limitations

A direct comparison of results and conclusions from the included papers was not possible given their variability in topics, contexts, and research methods. While some of the papers identified potential interventions, none of them presented specific data that would permit a quantification of the impact of their interventions on health outcomes. Specific to context, the evidence reviewed largely focused on urban environments, with only one of the included papers specifically focused on a suburban context. Finally, none of the papers examined the effects of interventions on specific sub-populations or comparatively across different areas.

Conclusion

The results of this literature review point to some promising practices around climate change mitigation and adaptation through the built environment that might be health-supportive and may be of some application to suburban settings. Key themes identified include opportunities presented by green infrastructure, building retrofit, and active transportation interventions. Cross-referencing these to the built form found in a traditional suburban context identifies certain barriers to implementation.

Further research and evaluation will help to determine, in suburban settings, how feasible such interventions might be, how they might be deployed, and how they might impact efforts to mitigate climate change and also adapt to protect general and vulnerable community populations from the direct and indirect health impacts of this phenomenon.

References

- Abhijith, K. V., Kumar, P., Gallagher, J., McNabola, A., Baldauf, R., Pilla, F., et al. (2017). Air pollution abatement performances of green infrastructure in open road and built-up street canyon environments–A review. Atmospheric Environment, 162, 71-86.

- Bourne, L. S. (1996). Reinventing the suburbs: Old myths and new realities. Progress in Planning, 46(3), 163-184.

- Buse, C. (2012). Report on Health Vulnerability to Climate Change: Assessing Exposure, Sensitivity, and Adaptive Capacity in the Region of Peel. Peel Public Health.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014). Climate Change and Public Health – Climate Effects on Health. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/climateandhealth/effects/default.htm

- Demuzere, M., Orru, K., Heidrich, O., Olazabal, E., Geneletti, D., Orru, H., et al. (2014). Mitigating and adapting to climate change: Multi-functional and multi-scale assessment of green urban infrastructure. Journal of environmental management, 146, 107-115.

- Ding, D., Gebel, K., Phongsavan, P., Bauman, A. E., & Merom, D. (2014). Driving: a road to unhealthy lifestyles and poor health outcomes. PloS one, 9(6), e94602.

- Frank, L. D., Greenwald, M. J., Winkelman, S., Chapman, J., & Kavage, S. (2010). Carbonless footprints: promoting health and climate stabilization through active transportation. Preventive medicine, 50, S99-S105.

- Gordon, D., & Janzen, M. (2013). Suburban nation? Estimating the size of Canada’s suburban population. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 30(3), 197-220.

- Gordon, D., & Shirokoff, I. (2014). Population Growth in Canadian Suburbs, 2006–2011. Kingston: School of Urban and Regional Planning, Queen’s Univ.

- Hatvani-Kovacs, G., Belusko, M., Skinner, N., Pockett, J., & Boland, J. (2016). Drivers and barriers to heat stress resilience. Science of the Total Environment, 571, 603-614.

- Hintz, M. J., Luederitz, C., Lang, D. J., & von Wehrden, H. (2018). Facing the heat: A systematic literature review exploring the transferability of solutions to cope with urban heat waves. Urban climate, 24, 714-727.

- Houghton, A., & Castillo-Salgado, C. (2017). Health co-benefits of green building design strategies and community resilience to urban flooding: A systematic review of the evidence. International journal of environmental research and public health, 14(12), 1519.

- Ibbitson, J. (2018) City growth dominated by car-driving suburbs, whose votes decide elections. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-city-growth-dominated-by-car-driving-suburbs-whose-votes-decide/

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2018). Global warming of 1.5°C. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. http://www.ipcc.ch/report/sr15/

- Leichenko, R. M., & Solecki, W. D. (2013). Climate change in suburbs: An exploration of key impacts and vulnerabilities. Urban Climate, 6, 82-97.

- Loh, L. C., & Brieger, W. B. (2014). Suburban sprawl in the developing world: Duplicating past mistakes? The case of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 34(2), 199-211.

- Natural Resources Canada (2019). Energy and Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHGs). Natural Resources Canada. https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/science-and-data/data-and-analysis/energy-data-and-analysis/energy-facts/energy-and-greenhouse-gas-emissions-ghgs/20063

- Page, J. L., Winston, R. J., & Hunt III, W. F. (2015). Soils beneath suspended pavements: An opportunity for stormwater control and treatment. Ecological Engineering, 82, 40-48.

- Pisello, A. L. (2017). State of the art on the development of cool coatings for buildings and cities. Solar Energy, 144, 660-680.

- Prior, J. H., Connon, I., McIntyre, E., Adams, J., Capon, T., Kent, J., et al. (2018). Built environment interventions for human and planetary health: integrating health in climate change adaption and mitigation. Public Health Research and Practice.

- Region of Peel (2016). Peel Data Centre – Population and Housing Estimates. Region of Peel. https://www.peelregion.ca/planning/pdc/data/population-est/population-housing-est.htm

- Region of Peel (2017). 2016 Census Bulletin Labour, Education & Mobility. Region of Peel. https://www.peelregion.ca/planning-maps/censusbulletins/2016-labour_education_mobility-bulletin.pdf

- Region of Peel (2017). 2016 Census Bulletin Immigration & Ethnic Diversity. Region of Peel. https://www.peelregion.ca/planning-maps/CensusBulletins/2016-immigration-ethnic -diversity.pdf

- Santamouris, M., Ding, L., Fiorito, F., Oldfield, P., Osmond, P., Paolini, R., et al. (2017). Passive and active cooling for the outdoor built environment–Analysis and assessment of the cooling potential of mitigation technologies using performance data from 220 large scale projects. Solar Energy, 154, 14-33.

- Stone Jr, B., Vargo, J., Liu, P., Hu, Y., & Russell, A. (2013). Climate change adaptation through urban heat management in Atlanta, Georgia. Environmental science & technology, 47(14), 7780-7786.

- Sugiyama, T., Neuhaus, M., Cole, R., Giles-Corti, B., & Owen, N. (2012). Destination and route attributes associated with adults’ walking: a review. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 44(7), 1275-1286.

- Thompson, D. (2013). Suburban sprawl: Exposing hidden costs, identifying innovations.

- Taylor, J., Wilkinson, P., Picetti, R., Symonds, P., Heaviside, C., Macintyre, H. L., et al. (2018). Comparison of built environment adaptations to heat exposure and mortality during hot weather, West Midlands region, UK. Environment international, 111, 287-294.

- Ulmer, J. M., Chapman, J. E., & MSA, S. E. K. (2015). Application of an evidence-based tool to evaluate health impacts of changes to the built environment. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 106(1), ES26.

- Van Dyck, D., De Meester, F., Cardon, G., Deforche, B., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2013). Physical environmental attributes and active transportation in Belgium: what about adults and adolescents living in the same neighborhoods?. American journal of health promotion, 27(5), 330-338.

- Watts, N., Amann, M., Arnell, N., Ayeb-Karlsson, S., Belesova, K., Berry, H., et al. (2018). The 2018 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: shaping the health of nations for centuries to come. The Lancet, 392(10163):2479–514.

- World Health Organization (2018). Climate change and health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health

- Williams, K., Joynt, J. L., & Hopkins, D. (2010). Adapting to climate change in the compact city: the suburban challenge. Built Environment, 36(1), 105-115.

- Williams, K., Joynt, J. L., Payne, C., Hopkins, D., & Smith, I. (2012). The conditions for, and challenges of, adapting England’s suburbs for climate change. Building and Environment, 55, 131-140.

- Williams, K., Gupta, R., Hopkins, D., Gregg, M., Payne, C., Joynt, J. L., et al. & Bates-Brkljac, N. (2013). Retrofitting England’s suburbs to adapt to climate change. Building Research & Information, 41(5), 517-531.