Red Mundial Para el Diagnóstico Médico - Tulaitula Health Consulting Group,Octubre 2015: Un sistema de información clínica para apoyar y facilitar el diagnóstico y tratamiento médicos en países con recursos limitados y en el resto del mundo

by Bashir Saiegh Saiegh DPH, MPH*

Fundador y CEO de Tulaitula Health Consulting Group

Red Mundial Para el Diagnóstico Médico

English version: World Network for Medical Diagnosis_PEAH (1)

RESUMEN DE LA IDEA PRINCIPAL

Se trata de construir una red médica basada en la innovación tecnológica y cuya finalidad sería la de lograr una alianza mundial entre los profesionales de la salud que contribuya a la reducción de las desigualdades sanitarias en todo el mundo, principalmente aquellas desigualdades derivadas de la escasez de acceso a conocimientos médicos avanzados, escasez de acceso a médicos especialistas y de otros profesionales sanitarios cualificados que padecen sobre todo las poblaciones de países pobres o en vías de desarrollo.

En definitiva, se trata de desarrollar e implementar un Sistema de Información Clínica patrocinado por una o más de las principales instituciones internacionales (OMS, Parlamento Europeo, Comisión Europea… etc.) para apoyar y facilitar el diagnóstico y tratamiento médicos en países sin recursos económicos suficientes con el propósito de transformar y mejorar el cuidado de la salud de sus poblaciones y promover una atención sanitaria basada en la evidencia de los datos. Se trataría de una red exclusiva para los profesionales sanitarios de todo el mundo cuya principal finalidad sería la de facilitar las interconsultas clínicas relacionadas con la salud de pacientes. De ella, podemos destacar los siguientes aspectos básicos:

- Es una red exclusiva para profesionales sanitarios. Esto incluye inicialmente a todos los médicos (médicos de familia o de atención primaria, cirujanos y demás especialistas) además de enfermeras y matronas. Más tarde se incluirá al resto de trabajadores sanitarios “todas las personas que participan en las acciones cuya intención principal es mejorar la salud” (OMS – Informe Mundial de la Salud 2006).

- Para unirse a la red, los médicos y demás profesionales sanitarios deben ser previamente identificados según la legislación vigente de cada país y de acuerdo a las normas de accesos y usos de la red.

- Los profesionales que ejercen como consultores médicos no tienen ningún poder de decisión directa sobre la salud del paciente, por lo que estarán exentos de cualquier responsabilidad legal, sólo actúan como asesores en materia de salud.

- En la interconsulta no se incluirá ningún dato que facilite la identificación personal de los pacientes.

- La interconsulta se hará a través de un resumen de historia clínica electrónica del paciente.

- Se podrán adjuntar imágenes, videos y otros documentos clínicos en soporte digital, siempre que no den lugar a la identificación personal del paciente.

- El sistema se desarrollará en los principales idiomas de la OMS e incluirá un traductor para facilitar la interconsulta clínica entre los diferentes países.

En definitiva, y con el fin de alcanzar la excelencia operativa de la red, pondremos a disposición de las instituciones interesadas todos los detalles técnicos de este proyecto incluyendo todos los detalles de este nuevo modelo de interconsulta médica y el flujo de datos de principio a fin que hemos diseñado para implementar este circuito innovador en la atención especializada. Estos circuitos y flujos de datos se construyeron a partir de una nueva visión médica para mejorar los cuidados de la salud y sostenida, no sólo sobre criterios de eficiencia y eficacia de la gestión, sino también y lo más importante aún, sustentada sobre criterios que garantizan la máxima calidad y seguridad del paciente.

Como ya hemos mencionado, nos pondremos a disposición de las instituciones interesadas para desarrollar, entregar y evaluar la Red Mundial para el diagnóstico médico, incluyendo:

- Los requerimientos básicos de funcionamiento

- La operatividad del sistema y los detalles técnicos de los flujos de datos

- Las normas de identificación y registro de usuarios

- La normativa de accesos y usos

- Las diferentes estrategias previstas

- El plan de actividades

- El detalle las distintas intervenciones

- El calendario de operaciones durante el primer año

- Los modelos de evaluación y los indicadores de resultados

- Presupuesto inicial, viabilidad financiera y el plan de sostenibilidad económica

JUSTIFICACIÓN

Según reconoce la OMS “en esta primera década del siglo XXI, enormes avances en el bienestar humano coexisten con privaciones extremas. En la salud mundial somos testigos de los beneficios que están aportando los nuevos medicamentos, tecnologías y conocimientos científicos, pero algunos de los países más pobres están sufriendo reveses sin precedentes. Esta creciente polarización en salud, ha llevado a que en algunas zonas del planeta, la esperanza de vida haya caído a la mitad respecto a los países más ricos”. Además reconoce que para avanzar en la lucha contra las desigualdades en salud, sería preciso que los interesados trabajen juntos mediante alianzas y redes – locales, nacionales y mundiales – abiertas a los diversos problemas sanitarios, profesiones, disciplinas, y países. Las estructuras cooperativas pueden mancomunar los limitados recursos económicos e intelectuales y fomentar la enseñanza recíproca.

El Informe Mundial de la Salud 2006 y la Estrategia Regional de Recursos Humanos para la Salud, 2006-2015; han cifrado una escasez mundial de 4,3 millones de trabajadores de la salud. Además, en las estadísticas mundiales de la Seguridad Social 2010/2011 (World Social Security Statistics 2010/2011) se afirmó que en la actualidad hay 100 países con una densidad de profesionales cualificados de la salud por debajo del umbral adecuado, traduciéndose en una escasez total de alrededor de 7,2 millones de profesionales sanitarios y que aumentarán a 12,9 millones en 2035 según unas las proyecciones sostenidas el crecimiento de la población. De modo que podemos afirmar que la escasez de personal sanitario especializado en el año 2015 es peor que en 2006 y es poco probable que esta tendencia se revierta en los próximos años. La idea de nuestro proyecto se basa en la necesidad de trabajar de inmediato para intentar reducir gradualmente las desigualdades sanitarias existentes en la actualidad. Especialmente en intentar reducir aquellas desigualdades relacionadas con el desigual acceso a los conocimientos médicos altamente especializados y que sufren las personas más pobres y las poblaciones más desfavorecidas donde la mayoría de ellos viven en las regiones más pobres del planeta y en los países con escasos recursos económicos y humanos.

Todos aquellos expertos de la gestión sanitaria que conocen en profundidad el funcionamiento de los más avanzados Sistemas Nacionales de Salud (SNS) y sus respectivos servicios sanitarios (Canadá, España, Inglaterra, Suecia…) saben que uno de los problemas más comunes y complejos de la gestión sanitaria es el derivado por la gran demanda y el alto costo de la interconsulta externa generada por la atención primaria hacia la atención especializada. A ello se le añade el problema de los largos tiempos de espera existentes para las consultas iniciales generados por la alta demanda lo que por otra parte genera evidentes desigualdades en el acceso a los conocimientos médicos especializados entre las diferentes regiones. Este gran volumen de demanda de interconsultas externas en la atención especializada, no es caprichosa y en parte, se basa en la alta especialización de la medicina y la amplia fragmentación del conocimiento médico (Sólo sé que no sé nada; Sócrates). Si esto está sucediendo en los servicios de salud más avanzados del mundo en donde la población sufre ciertas desigualdades de acceso a los conocimientos médicos especializados en función de su zona de residencia, que es lo que está sucediendo en las regiones y países más pobres del planeta? Sin entrar en detalles, me imagino que la mayoría de expertos estarían de acuerdo en afirmar que la mayoría de estas personas no tienen acceso adecuado a la medicina especializada. Por otra parte, se podría presuponer que la mayoría de los médicos que trabajan en estos países carecen del apoyo esencial y necesario de otros médicos especialistas, lo que realmente es grave y repercute negativamente en la salud de los pacientes. Las razones son varias y bien conocidas por todos nosotros; la ausencia de SNS, la escasez de recursos económicos, la falta de personal médico especializado…etc.

Por lo tanto, de los múltiples factores determinantes de las desigualdades en salud, nuestro proyecto, aunque sea parcialmente, podría responder con eficiencia y eficacia a dos de los principales factores:

- La escasez de personal sanitario cualificado o la escasez de médicos especialistas: esa escasez tiene carácter mundial, pero reviste especial gravedad en los países más pobres donde más los necesitan “Informe Mundial de la Salud 2006”.

- La inequidad de acceso a personal médico especializado motivada por razones económicas: La atención sanitaria es una industria de servicios basada fundamentalmente en el capital humano, donde una fuerza de trabajo cualificada, elemento clave de todos los sistemas sanitarios, es fundamental para hacer progresar la salud. Existen evidencias científicas y abundantes pruebas de que el número, la calidad y la densidad de distribución de los trabajadores sanitarios están efectivamente relacionados con la cobertura de inmunización, la supervivencia de los lactantes, los niños y las madres así como con resultados positivos en el ámbito de las enfermedades cardiovasculares, infecciosas y demás problemas de salud.

SOLIDARIDAD Y ALIANZA MUNDIAL DE LOS INTERESADOS COMO FUNDAMENTOS

En palabras del propio Informe Mundial de Salud 2006 – Colaboremos por la salud, por bien concebidas que estén, las estrategias nacionales no bastan por sí solas para hacer frente a la realidad de los desafíos que plantea y planteará la escasez del personal sanitario. Están igualmente condicionadas en unos países y otros por el carácter fragmentario de las pruebas, lo limitado de los instrumentos de planificación y la escasez de conocimientos técnicos especializados. Por tanto, el presente proyecto se plantea, dentro del marco de la cooperación internacional, como un esfuerzo solidario entre la comunidad médica mundial que complemente los liderazgos nacionales, por lo menos en cinco frentes:

- Mejorar la inequidad de acceso a personal médico especializado.

- Catalizar y difundir el conocimiento médico, las competencias técnicas y las prácticas sanitarias óptimas. La mancomunación eficaz del conocimiento médico especializado y de las diversas competencias técnicas y el amplio abanico de experiencias pueden ayudar a los países a tener acceso a conocimientos profesionales más avanzados y a prácticas más óptimas para mejorar la salud de sus poblaciones.

Fomentar la enseñanza recíproca y el aprendizaje mutuo.

- Alcanzar acuerdos de cooperación sociosanitarios.

- Responder a la crisis por la escasez de personal sanitario especializado. Esta crisis en los países más pobres es de una importancia innegable y exige una respuesta urgente, sostenida y coordinada por parte de la comunidad internacional. Todos los asociados deben analizar críticamente por qué medios apoyan a éste, con miras a eliminar las prácticas poco eficientes y coordinar más eficazmente sus acciones con las autoridades nacionales competentes.

Apoyamos la idea de que el liderazgo nacional y la solidaridad mundial pueden y deben lograr importantes mejoras estructurales de la fuerza de trabajo en todos los países, y en especial en los que padecen crisis más graves. Estos avances se caracterizarían por el acceso universal a un personal sanitario motivado, competente y bien respaldado por otros compañeros altamente cualificados.

De ahí nuestra propuesta de construir un sistema de información clínica para apoyar y facilitar el diagnóstico y tratamiento médicos en todo el mundo. A nuestro entender, el proyecto planteado, ayudará de forma efectiva a lograr mejoras de la fuerza de trabajo sanitario en los países que más padecen la escasez de estos recursos y propiciará una mejora inmediata de la atención sanitaria mediante el apoyo técnico especializado que contribuirá a conseguir una mejora en la salud de las poblaciones atendidas.

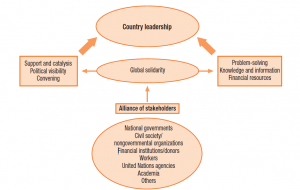

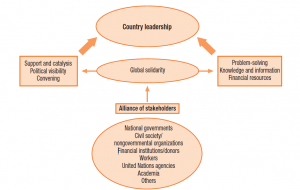

Nuestra propuesta se basa en la idea de la solidaridad global que ilustra la siguiente figura de cómo podría crearse una alianza mundial de la fuerza de trabajo en salud y que impulse a las partes interesadas a acelerar la lucha contra las desigualdades en salud.

The World Health Report 2006: Figure 5 Global stakeholder alliance

OBJETIVOS DEL PROYECTO E IMPACTO EN SALUD

OBJECTIVO GENERAL / OBJECTIVO ESTRATEGICO

El presente proyecto tiene por objeto contribuir a la reducción de las desigualdades en materia de salud en especial las desigualdades de acceso que sufren las poblaciones más desfavorecidas. Se trata principalmente de reducir aquellas desigualdades generadas por el limitado acceso al conocimiento médico especializado y por el desigual acceso a personal sanitario altamente especializado.

Por lo tanto, el objetivo general sería fortalecer, apoyar y mejorar la capacidad técnica del personal sanitario de todo el mundo en especial de los países con recursos limitados. Se trata de proporcionarles una forma sencilla de solicitar una ayuda para apoyar el diagnóstico y tratamiento a través de una interconsulta dirigido al personal cooperante de la atención especializada que está asociado a la Red Mundial para el diagnóstico médico. De esta manera pueden mejorar su respuesta a los desafíos sanitarios habituales o emergentes que afrontan en sus labores diarias.

OBJETIVO ESPECÍFICO

El propósito específico sería construir una red médica basada en la innovación tecnológica y cuya finalidad sería la de lograr una alianza mundial de profesionales sanitarios, donde los trabajadores de los servicios públicos de salud de los países con recursos limitados, principalmente aquellos que desarrollan su labor en áreas rurales, suburbios o zonas alejadas, puedan tener de inmediato un apoyo médico especializado que de otra manera no obtendrían. Esto conduce necesariamente a mejorar la salud de la población atendida que de otra manera sería más difícil de lograr.

OBJETIVO SECUNDARIOS

- Catalizar, facilitar y difundir la experiencia médica especializada y las mejores prácticas en salud.

- Promover el conocimiento médico recíproco y el aprendizaje mutuo.

- Contribuir a la difusión del conocimiento médico basado en la evidencia y hacerlo accesible a las poblaciones más pobres y a las regiones más remotas.

- Contribuir a proporcionar un apoyo técnico sólido y a una mejor gestión y difusión del conocimiento científico.

- Mejorar la capacidad técnica de los médicos y demás trabajadores sanitarios de los servicios públicos de salud de los países con recursos limitados. Esta mejora en la capacitación técnica médica, conduce necesariamente a mejorar la salud de la población atendida.

- Mejorar las capacidades técnicas de los médicos de los países desarrollados en áreas específicas, tales como las enfermedades tropicales y emergentes. Esta mejora en la capacitación técnica médica, conduce necesariamente a mejorar la salud de la población atendida.

- Mejorar la confianza de las poblaciones en los servicios públicos de salud de sus respectivos países.

- Actuar como una plataforma dinámica, confidencial y segura que facilite una rápida comunicación entre profesionales sanitarios de distintos países.

- Constituirse en un sistema complementario de alerta para mejorar la detección geográfica de las necesidades médicas más acuciantes con la finalidad de mejorar la efectividad de las respuestas de cooperación sanitaria.

- Constituirse en una plataforma de apoyo a las redes existentes de alertas en Salud Pública y Epidemiología para todo el mundo (red auxiliar de vigilancia epidemiológica).

- Contribuir a la promoción de las políticas sanitarias saludables.

- Contribuir a mejorar la eficacia y la productividad de los SNS y de los respectivos servicios sanitarios de los países cooperantes.

- Contribuir al desarrollo tecnológico de las regiones más desfavorecidas. Mediante los acuerdos de cooperación, tanto con los países donantes como con los gobiernos de los países receptores, y como respuesta a la posible ausencia de recursos informáticos en determinadas regiones, se fomentaría:

- Equipar con terminales informáticas a los centros de salud o puntos sanitarios en las regiones carentes de ellas.

- El establecimiento de conexiones a la red, especialmente vía satélite.

- Implantación de generadores de energías limpias; paneles solares, aerogeneradores…etc.

- Contribuir al desarrollo económico de las regiones desfavorecidas. Las actividades antes enumeradas, fomentarían la creación de empleos verdes y de alta tecnología.

- Aspirar, en un futuro no muy lejano, a convertirse en una plataforma médica de base tecnológica que, mediante el establecimiento de videoconferencia o conferencias de audio, los profesionales cualificados pueden prestar apoyo directo a trabajadores de salud menos calificados para dar respuestas inmediatas a situaciones de emergencia (nacimientos, fracturas, cirugía, … etc.)

- Convertirse en la plataforma de comunicación entre el personal sanitario a nivel internacional con todos los beneficios que ello conlleva:

- Facilitar la difusión de los comunicados de la OMS y las demás instituciones internacionales relacionadas con la salud.

- Facilitar la libre difusión de las publicaciones médicas y los resultados de la investigación en salud.

- Otros beneficios.

POBLACIÓN DIANA

Las poblaciones de los países con recursos limitados cuyos servicios sanitarios públicos padecen una profunda escasez de personal sanitario cualificado. Aunque el beneficio final podría llegar a toda la población mundial.

ÁMBITO Y PARTICIPANTES

Los profesionales sanitarios (especialista médicos, matronas,…) “todas las personas que participan en las acciones cuya intención principal es mejorar la salud” (OMS – IMS 2006) que a través de la red proporcionarán una consultoría clínica especializada y prestarán un apoyo técnico cualificado a los profesionales de los servicios sanitarios públicos de los países con limitados recursos y de las regiones más pobres del planeta.

VENTAJAS E INCONVENIENTES

Al igual que cualquier otro, este proyecto presenta fortalezas y debilidades. De entre sus ventajas, se destaca la utilidad del mismo para contribuir a reducir las desigualdades de acceso en salud. De entre sus desventajas, se destaca la probabilidad de que muchos centros de salud carezcan de las terminales informáticas necesarias o que puedan tener dificultades de acceso a la red, aunque ello podría ser una oportunidad de ir ampliando el alcance de las nuevas tecnologías a las regiones en desarrollo. En la siguiente tabla, se resumen las ventajas y los inconvenientes del proyecto propuesto.

| VENTAJAS |

INCONVENIENTES |

| 1. Útil2. Solidario e igualitario3. Oportuno4. Asequible, seguro y confidencial5. Universal

6. Eficiente y eficaz

7. Transparente

8. Consistente y fiable

9. Práctico y duradero en el tiempo

10. Simple y fácil de usar

11. Rápido

12. Objetivo

13. Flexible y fácilmente adaptable

14. Actualizable

15. Ausencia de incentivos perversos |

16. El acceso limitado a la red de los trabajadores de la salud de algunos países con recursos limitados17. La financiación inicial18. La dependencia inicial de la voluntad política |

Cabe destacar que nuestra intención es transformar los posibles inconvenientes antes mencionado en oportunidades reales de mejora como ya hemos mencionado en el punto 13 de los objetivos secundarios. Estas actividades promoverán la creación de empleos verdes y de alta tecnología en las regiones que realmente los necesitan. Por otro lado, con la implementación de este proyecto, las circunstancias y las posibilidades de cooperar proporcionando apoyo médico especializado será más fácil, sencillo, cómodo y rápido al no tener que viajar muy lejos, donde el profesional colaborador podrá cooperar en cualquier momento y desde cualquier lugar.

SEGURIDAD JURÍDICA Y RESPONSABILIDADES LEGALES

Cabe destacar que nuestra intención es transformar los posibles inconvenientes antes mencionado en oportunidades reales de mejora como ya hemos mencionado en el punto 13 de los objetivos secundarios. Estas actividades promoverán la creación de empleos verdes y de alta tecnología en las regiones que realmente los necesitan. Por otro lado, con la implementación de este proyecto, las circunstancias y las posibilidades de cooperar proporcionando apoyo médico especializado será más fácil, sencillo, cómodo y rápido al no tener que viajar muy lejos, donde el profesional colaborador podrá cooperar en cualquier momento y desde cualquier lugar.

Al ser este un proyecto de consultoría médica por red telemática, los profesionales sanitarios cooperantes ejercerían de simples consultores sin ninguna capacidad decisoria final sobre el paciente, por lo que estarán eximidos de cualquier responsabilidad legal o jurídica vinculante. Los profesionales sanitarios demandantes del apoyo técnico, son y serán los únicos responsables legales de sus propios actos, por lo que tomarán sus decisiones de forma autónoma con independencia de la opinión de los consultores cooperantes.

SOLIDEZ DEL PROYECTO

DIFERENCIACION DE LAS PRACTICAS EXISTENTES Y PERTINENCIA DE LA ACCION:

El proyecto se basa en una idea innovadora en materia de cooperación; cuya finalidad sería la de rentabilizar más y mejor los inmensos recursos tecnológicos, informáticos y humanos disponibles para proporcionar apoyo médico especializado y soporte sanitario cualificado a los profesionales de los servicios sanitarios públicos de todo el mundo, principalmente a aquellos que trabajan en países con recursos limitados y en las regiones pobres, de una forma sencilla y segura, sin incurrir en ningún coste adicional para las arcas públicas. El uso de la red y la cooperación voluntaria brindarán a las personas más desfavorecidas la oportunidad de acceder a los conocimientos médicos especializados que de otro modo y, por el momento, no les sería posible acceder con todo lo que ello supondría para la mejora de salud y lo que podría significar en la lucha contra las desigualdades en salud. Pensamos que la labor de sensibilización encaminada a situar y mantener la necesidad de cooperación y participación voluntaria del personal sanitario de los servicios sanitarios avanzados en un lugar destacado de su agenda diaria, no resultaría un desafío complicado. La mayoría de estos profesionales tendrían la oportunidad de prestar ayuda a los pueblos más necesitados en cualquier momento y desde cualquier lugar, sin que para ello tengan que desplazarse del sillón de su casa o de su puesto de trabajo.

EFECTIVIDAD Y VIABILIDAD DE LA ACCION:

La claridad del plan de actividades que propondremos y la factibilidad de su aplicación, nos invitan a ser optimistas acerca de la viabilidad del proyecto. Como se podrá comprobar en el plan, cada objetivo estratégico se acompaña de varios objetivos operativos. El cumplimiento de los objetivos operativos planteados se garantizará mediante la implementación de una serie de actividades y prácticas acordes a la consecución de los mismos donde, cada actividad cuenta con un responsable y un tiempo máximo para su ejecución, pudiendo ser las mismas objetivamente verificables al finalizar el periodo de fijado para su consecución. De este modo, los indicadores del resultado de cada acción deberán verificar objetivamente el logro de los objetivos y su grado de implementación.

IMPACTO ESTRUCTURAL DESEADO Y SOSTENIBILIDAD DE LA ACCION:

En el plan de actividades se detallarán los efectos multiplicadores en materia de salud que va a lograr la implementación y puesta en marcha de la red. El lanzamiento mundial del proyecto tendría que reproducir las actuaciones efectivas del periodo piloto procurando aplicar aquellas medidas que más éxitos hayan tenido en esta primera fase. De modo que, mediante la implantación del presente proyecto, y reconociendo que parte de las siguientes aspiraciones se fundamentan en la inmensa ilusión depositada en el mismo, en los próximos 5 a 10 años desde su implantación se aspira a obtener los siguientes efectos tangibles:

- Responder a más de cinco millones de interconsultas médicas especializadas que de otro modo no podrían haber ocurrido.

- Establecer más de 3 millones de planes de cuidados de enfermería.

- Establecer más de 1 millón de planes de cuidados sociosanitarios y de salud mental.

- Haber contribuido a mejorar la calidad de la atención sanitaria en todo el mundo.

- Haberse constituido en la plataforma de comunicación profesional de referencia entre los profesionales de salud a nivel mundial.

- Haberse contribuido a catalizar y difundir el conocimiento médico, las competencias técnicas, el conocimiento científico y las prácticas sanitarias más óptimas.

- Haberse contribuido a la mejora de la detección geográfica de las necesidades sanitarias más acuciantes en las distintitas regiones del planeta.

- Haber difundido más de 100.000 artículos, notas o comunicaciones científicas relacionadas con la promoción de las políticas públicas sociosanitarias más saludables.

- Haber contribuido a la introducción e implantación de más de 50.000 terminales informáticas en los centros de salud de las regiones más pobres, haber contribuido a conectarse a la red de más de 5.000 regiones aisladas y de haber contribuido a la implantación de más de 500 nuevos generadores de energía limpia en regiones carentes de ella.

- Otros impactos.

SOSTENIBILIDAD DE LOS RESULTADOS PREVISTOS DERIVADOS DE LAS ACTIVIDADES PROPUESTAS:

Más adelante pondremos a disposición de la institución interesada los planes que detallan la sostenibilidad económica del proyecto y los planes que garanticen la financiación futura de las actividades. Por otra parte, cabe destacar que la sostenibilidad institucional del proyecto quedaría garantizada por la acción continuada que se llevaría a cabo tal y como se detallará en el plan de actividades. Las infraestructuras establecidas, los acuerdos alcanzados, la implicación activa de los distintos actores y los efectos positivos cosechados garantizarán el funcionamiento futuro de la red con independencia de las voluntades personales. Finalmente destacar los impactos positivos que se tendrían por la aplicación del proyecto en lo que respecta a las políticas sociosanitarias y medioambientales y a las que antes nos hemos referido.

CONCLUSIÓN

OMS “No hay atajos y no hay tiempo que perder. Ahora es el momento de actuar, de invertir en el futuro, y para promover la salud rápidamente y de manera equitativa”

No hay soluciones fáciles y no hay consenso en cuanto a la forma de actuar. Sin embargo, todos sabemos que el factor humano es esencial para fortalecer los sistemas de salud y mejorar las posibilidades de supervivencia de las personas y su bienestar. Esto significa que tendríamos que invertir mucho tiempo y dinero en la formación de los trabajadores sanitarios, por lo que creemos que este proyecto ayudará a lograr estos objetivos e intentará responder de alguna manera a ese problema facilitando la capacitación de los profesionales sanitarios con ahorro de tiempo y dinero contribuyendo así a la solución del mismo.

La comunidad internacional (OMS, UNAIDS, BANCO MUNDIAL, Organización para la Cooperación Económica y el Desarrollo,…) cuenta con los recursos económicos suficientes para intentar hacer frente a una buena parte de estos desafíos sanitarios. También sabemos que lo que se necesitaría es una voluntad política para poner en marcha nuevas medidas de cooperación internacional con el fin de coordinar los recursos, aprovechar los conocimientos y prestar apoyo para desarrollar sistemas sanitarios robustos que traten y prevengan las enfermedades y promuevan la salud de la población principalmente en aquellos países que carecen de los recursos suficientes. Estamos seguros de que este proyecto contribuirá a la consecución de los objetivos antes mencionados y a la mejora y protección de la salud en todo el mundo, pero ello no sería posible sin el apoyo directo y sincero de la OMS y/o de otras instituciones sanitarias internacionales con una clara apuesta por la innovación sanitaria como una herramienta segura para mejorar y hacer progresar la salud de la población mundial.

Creemos que todos los esfuerzos para reducir las desigualdades en salud son dignos de ser estudiados y evaluados por lo que pensamos que vale la pena apostar por la creación, desarrollo, implantación y promoción de la Red Mundial para el Diagnóstico Médico que proponemos en esta publicación como una nueva e innovadora herramienta sanitaria que contribuirá a la lucha contra las desigualdades en salud y reducirá la inequidad de accesos al conocimiento médico especializado.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

- World Health Organization. The World Health Repor 2006: Working together for health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. Available at: http://www.who.int/whr/2006/whr06_en.pdf

- Brent D Fulton, Richard M Scheffler, Susan P Sparkes, Erica Yoonkyung Auh, Marko Vujicic, Agnes Soucat. Health workforce skill mix and task shifting in low income countries: a review of recent evidence. Human Resources for Health 2011, 9(1:11). Available at: http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1478-4491-9-1.pdfREVIEW

- Campbell J, Dussault G, Buchan J, Pozo-Martin F, Guerra Arias M, Leone C, Siyam A, Cometto G. A universal truth: no health without Forum Report, Third Global Forum on Human Resources for Health, Recife, Brazil. Geneva, Global Health Workforce lliance and World Health Organization, 2013. Available at: http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/resources/GHWA-a_universal_truth_report.pdf?ua=1

- Mohan Rao, Krishna D Rao, A K Shiva Kumar, Mirai Chatterjee, Thiagarajan Sundararaman. Human resources for health in India. Public Health Foundation of India, New Delhi, India. The lancet 2011, 377:587-598. Available at: http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0140673610618880/1-s2.0-S0140673610618880-main.pdf?_tid=683983a6-6cef-11e5-bbe1-00000aab0f01&acdnat=1444221300_0ae0580091f43445b1cd620cb8594a51

- Stephen J Duckett. Health workforce design for the 21st century. Aust Health Rev 2005: 29(2): 201–210. Available at: http://www.publish.csiro.au/?act=view_file&file_id=AH050201.pdf

- Hu Yun, Shen Jie, Jiang Anli. Nursing shortage in China: State, causes, and strategy Nursing Outlook, Volume 58, Issue 3, May–June 2010, Pages 122–128. Available at: http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0029655409002358/1-s2.0-S0029655409002358-main.pdf?_tid=273561f4-6d94-11e5-a7e7-00000aab0f02&acdnat=1444292058_6a0b172b29f55a165383e657df84a11f

- Araujo, Edson; Maeda, Akiko. 2013. How to recruit and retain health workers in rural and remote areas in developing countries. Health, Nutrition and Population (HNP) discussion paper. Washington DC ; World Bank. Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2013/06/17872903/recruit-retain-health-workers-rural-remote-areas-developing-countries

- United Nations Human Development Report 2009. “Statistics of the Human Development Report.” United Nations. 2009. Accessed June 22, 2010.

- Shrikant I. Bangdiwala, Sharon Fonn, Osegbeaghe Okoye , Stephen Tollman. Workforce Resources for Health in Developing Countries. Public Health Reviews, Vol. 32, No 1, 296-318. Available at: http://www.publichealthreviews.eu/upload/pdf_files/7/17_Workforce.pdf

- Haroon Wadee, Farzana Khan. Human Resources for Health Available at: http://www.hst.org.za/uploads/files/chap9_07.pdf

- Wildschut, A., & Mgqolozana, T. (2009). Nurses. In J. Erasmus & M. Breier (Eds.), Skills shortage in South Africa: case studies of key professions. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

- World Health Organisation. (2006a). The global shortage of health workers and its impact. Available at: http://www.unep.org/training/programmes/Instructor%20Version/Part_2/Activities/Dimensions_of_Human_Well-Being/Health/Supplemental/Global_Shortage_of_Health_Workers.pdf.

- Executive Summary / 2011 Progress Report on the PIHOA Nahlap Resolution and Action Plan for Human Resources for Health, dated August 2006, The Pacific Island Health Officers Association, March 2011, pages 6-12.

- Swiss Contributions to Human Resources for Health Development in Low- and Middle-Income Countries” commissioned by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) .The full report can be downloaded from http://www.deza.admin.ch/de/Home/Themen/Gesundheit/Gesundheitssysteme_und_dienstleistungen

- James MacKinnon and Barbara MacLaren. 2012. Human Resources for Health Challenges in Fragile States: Evidence from Sierra Leone, South Sudan and Zimbabwe. Available at: http://www.nsi-ins.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/2012-Human-Resources-for-Health-Challenges-in-Fragile-States.pdf

- Nancy Gerein,a Andrew Green,b Stephen Pearsonc. The Implications of Shortages of Health Professionals for Maternal Health in Sub-Saharan Africa Reproductive Health Matters 2006;14(27):40–50. Available at: http://www.rhm-elsevier.com/article/S0968-8080(06)27225-2/pdf

- Churnrurtai Kanchanachitra, Magnus Lindelow, Timothy Johnston, Piya Hanvoravongchai, Prof Fely Marilyn Lorenzo, Nguyen Lan Huong, Siswanto Agus Wilopo, Jennifer Frances dela Rosa. Human resources for health in southeast Asia: shortages, distributional challenges, and international trade in health services. The Lancet, 26 February 2011. p769–781, Available at: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(10)62035-1/abstract

- Hongoro, Charles et al. How to bridge the gap in human resources for health. The Lancet , Volume 364 , Issue 9443 , 1451 – 1456. Available at: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(04)17229-2/abstract

- Stephen J Duckett. Health workforce design for the 21st century. Aust Health Rev 2005: 29(2): 201–210. Available at: http://www.publish.csiro.au/?act=view_file&file_id=AH050201.pdf

- Stella C. E. Anyangwe and Chipayeni Mtonga. Inequities in the Global Health Workforce: The Greatest Impediment to Health in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2007, 4(2), 93-100. Available at: http://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/4/2/93/htm

- IHS Inc., The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2013 to 2025. Prepared for the Association of American Medical Colleges. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2015. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/426242/data/ihsreportdownload.pdf?cm_mmc=AAMC-_-ScientificAffairs-_-PDF-_-ihsreport

- Alicia Gallegos, special to the Reporter. Medical Experts Say Physician Shortage Goes Beyond Primary Care

- AAMC Reporter: February 2014. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/reporter/february2014/370350/physician-shortage.html

- Paula O’Brien and Lawrence O. Gostin. Health Worker Shortages and Global Justice. Milbank Memorial Fund. Available at: http://www.milbank.org/uploads/documents/HealthWorkerShortagesfinal.pdf

- US Department of Health and Human Services. 2010. HHS Awards $96 Million to Train Health Professionals. Press release, July 1. Available at: https://wayback.archive-it.org/3926/20131018160710/http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2010pres/07/20100701f.html.

- Pick, W. 2008. Lack of Evidence Hampers Human-Resources Policy Making. The Lancet 371(9613):629–30. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18295008.

- World Health Organization. 2010. Global Atlas of the Health Workforce. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available at: http://apps.who.int/globalatlas/default.asp.

- Bach, S. International Migration of Health Workers: Labor and Social Issues. Geneva: Sectoral Activities, Working Paper, International Labor Organization, 2003.

- Workforce Training and Education Coordinating Board. Health Care Personnel Shortage Task Force. 2012 Annual Report. Available at: http://www.wtb.wa.gov/documents/healthcarereport2012.pdf

- First Consulting Group. The Healthcare Workforce Shortage and Its Implications for America’s Hospitals Fall 2001. Available at: file:///C:/Users/Daniele/Downloads/FcgWorkforceReport.pdf

- Paula O’Brien and Lawrence O. Gostin. Health Worker Shortages and Inequalities: The Reform of United States Policy.

- Organization for Economic Development. The Looming Crisis in the Health Workforce: How Can OECD Countries Respond? OECD Health Policy Series, 2008, 14. Global Health Governance, Volume II, No. 2 (Fall 2008/Spring 2009). Available at: http://www.ghgj.org

- Edward J. Mills, William A. Schabas, et al., “Should Active Recruitment of Health Workers from Sub-Saharan Africa Be Viewed as a Crime?” The Lancet 371, no. 9613 (2008): 685 – 88; World Health Organization, Global Atlas of the Health Workforce, March 2008. Available at: http://www.who.int/globalatlas/default.asp

- Naicker S, Plange-Rhule J, Tutt RC, Eastwood JB. Shortage of healthcare workers in developing countries–Africa. Ethn Dis. 2009 Spring;19(1 Suppl 1):S1-60-4. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19484878

- Glob Health Action 2014, 7: 23611 – http://www.globalhealthaction.net/index.php/gha/article/view/23611

*Bashir Saiegh Saiegh Doctor Suma Cum Laude en Medicina y Salud Pública, Especialista en Salud Pública, Epidemiología y Medicina Preventiva, Especialista en Sistemas Clínicos de Información y Especialista en Gestión Sanitaria. Experto en: Sistemas Nacionales de Salud, Políticas de Salud Pública, Políticas de Salud Global y en Políticas Sanitarias. Fundador y CEO de Tulaitula Health Consulting Group.

Tulaitula Health Consulting Group, todos los derechos reservados. Este proyecto ha sido desarrollado y enviado para contribuir a mejorar las políticas de acceso equitativo a la salud. El autor ha tomado todas las precauciones posibles y ha verificado toda la información contenida en esta publicación. Las solicitudes de autorización para reproducir o traducir esta publicación, así como para cualquier otra información relacionada con el contenido del proyecto deberán dirigirse al correo electrónico: manager@tulaitula.com

Agradecimientos: mi gratitud al Dr. Daniele Dionisio por su interés y por la oportunidad que me ha dado para colaborar y tratar de contribuir a las políticas para el acceso equitativo a la salud “Policies for Equitable Access to Health”. Así mismo hago constar mis agradecimientos a todas las personas que están trabajando y contribuyendo a la reducción de las desigualdades en salud en todo el mundo, incluidos los miembros del “EP Working Group on Innovation, Access to Medicines and Poverty-Related Diseases”.