This invitation is not just about ‘sharing vaccines when a pandemic occurs’, it is not about ‘more global funding by the G7 or G20’ nor about ‘temporary waivers of IPR. This proposal is about global action to work towards an effective Global R&D Preparedness Ecosystem – and to improve the R&D capability of low- and middle-income countries as essential component of global preparedness and R&D Equity A pragmatic conceptualization of a Global R&D Ecosystem opens the doors to purposeful participation by any country, no matter their stage of scientific and economic development. Any country can and should co-create, make improvements and be supported in their efforts to improve their capacity for R&D and towards scaling knowledge and products for equitable responses to any global threat. R&D Equity is core to achieving the SDG 2030 agenda and essential to pursuing global health, equity and development in the decades to come

Global R&D Equity

Essential Link to Global Preparedness

INVITATION to ACT

Council on Health Research for Development (COHRED)

September 2021

Contact person for information, explanation or expression of interest: Prof. Carel IJsselmuiden, Executive Director COHRED 1-5 route des Morillons, 1211 Geneva, Switzerland cohred@cohred.org

The purpose of this call to action is to co-create a unique platform to strengthen the Research and Development (R&D) ecosystems of low- and middle-income countries as an essential component of global preparedness and efforts to realize the sustainable development goals.

This invitation is, in first instance, directed at nations as those that implement and lead.

Beyond nations, this invitation is to all others committed to support the growth of capable R&D ecosystems in low- and middle-income countries.

Dependence on global solidarity and generosity is not a reliable approach to global preparedness – neither for pandemics nor for global challenges resulting from climate change, growing socio-economic inequities and other major determinants of global health and well-being. A capable and flexible Global R&D Ecosystem comprising capable and re-purposable national R&D ecosystems – including in low- and middle-income countries – is a far better option for global preparedness and equitable access.

The R&D Equity initiative is uniquely positioned to achieving that.

Solving Vaccine Inequity requires R&D Equity

Contents

Introduction

- Lessons in Global Preparedness from the COVID-19 Pandemic

Why is global R&D Equity necessary for the future preparedness?

Global R&D Equity confers a safer future for everyone

- Global Pandemic Preparedness – a multitude of actions but no comprehensive global plan for equitable prevention, preparedness and control

- R&D Equity – the action agenda

Supporting the SDG 2030 Agenda

Creating a platform for comprehensive global action in R&D preparedness

- Financial and Other Engagements to support the Commission’s work

- Working with COHRED

Appendix

Key Reference Documents

Abbreviations used

Introduction

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates that the world is not yet geared to deal effectively and equitably with the prevention and control of major global challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the systemic inequities that pervade our societies and that are fundamental to our collective inability for rapid and effective control of the pandemic. “Vaccine inequity” and “vaccine nationalism” are both key symptoms and causes of ineffective pandemic control. They are a failure of both global justice and of global preparedness.

There is no reason to believe that the world is any better prepared to address other global challenges to health, well-being and equitable development, including challenges expected to result from climate change, threats to water and food security, and growing socio-economic inequities.

Yet, it does not have to be this way. The COVID-19 pandemic is also showing that – as a global community – we are becoming better at global collaboration, science sharing, technological innovation, and scaling production of interventions that work. These are highly positive developments on which to build the global vision and value of R&D Equity.

One of the most important but under-recognized developments in the control of the current pandemic is the active participation of middle-income countries in producing and scaling equipment, diagnostics and vaccines. Global health and development have for decades relied overwhelmingly on high-income countries’ expertise, finances and goodwill. This is now being replaced by a new paradigm in which middle-income countries are or are becoming equal partners in the global pandemic response. Thanks to the contributions by China, India, Russia and the potential contributions by many other countries such as the Philippines, South Africa, Mexico, Cuba, Thailand, Senegal and others, control can be much more rapid, effective and equitable for low- and middle-income countries accelerating global pandemic control at the same time. With the political, technical and financial support from high-income countries wishing this development to grow and succeed, meaningful technology transfer may begin to occur.

To build a world that is truly prepared – for everyone – we need to build on these major advancements. The ability of countries and regions to use and share science, use and share research and development, and do so in a spirit of partnership, solidarity and with a view to global impact is what will determine how quickly and effectively future challenges can be prevented and controlled.

A pragmatic conceptualization of a Global R&D Ecosystem opens the doors to purposeful participation by any country, no matter their stage of scientific and economic development. Any country can and should co-create, make improvements and be supported in their efforts to improve their capacity for R&D and towards scaling knowledge and products for equitable responses to any global threat.

R&D Equity is core to achieving the SDG 2030 agenda and essential to pursuing global health, equity and development in the decades to come.

- Lessons in Global Preparedness from the COVID-19 Pandemic

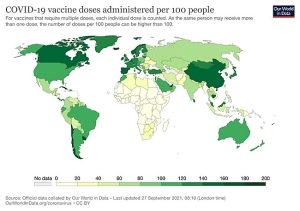

The COVID-19 pandemic is far from over and the global response is at a critical phase. Stark contrasts still undermine progress, with vaccine inequity being one of the most urgent and visible issues, posing a threat to ending the pandemic and to global recovery. Over 75% of all vaccine doses have been administered in only 10 countries while the lowest income countries have administered less than half a percent of global doses – at this time.

Why is global R&D Equity necessary for future preparedness?

“A pandemic is not over until it is over everywhere”.

A major obstacle to pandemic control is that many countries do not possess the R&D institutions, trained human work force, technical and production capabilities and financing facilities – they do not have the capable R&D ecosystems needed for local preparedness and control. As a result, global preparedness fails as well. Neither global vaccine donations nor ‘temporary IP waivers’ are sufficient nor timely, and neither enable countries to begin solving their own problems – let alone being able to contribute to global pandemic control.

The solution to solving global problems cannot be found in a world returning to its past – in which high-income countries use their expertise, their funding, their approaches and their sense of solidarity to solve the problem for others – and, at the same time, fail to address the fundamental underlying inequities. This cannot remain the model for the future. Low- and Middle-Income Countries have to be active participants in developing their own and the global R&D ecosystems.

A defining feature of the current global preparedness is that national investments in R&D capacity have been the real driver of change. In high-income countries with the investment in basic science leading to the development of mRNA vaccines, and in middle-income countries with their ability to scale production for other low- and middle-income countries. Without the vaccines and technical support of China, Russia, India and other middle-income countries such as Mexico and South Africa, that have actively invested in the growth and development of their own R&D ecosystems, this pandemic will continue for much longer.

Having capable R&D ecosystems to address their own health, equity and development challenges without having to depend solely on high-income country support is essential for a better, healthier, more equitable and a safer world for everyone.

Global R&D Equity confers a safer future for everyone

Countries with high-performing R&D systems and infrastructure, including local and international partnerships and networks, can use this capability also to address many other global developmental challenges. R&D system growth as a result of COVID-19 pandemic control can be repurposed to address the health, economic, and sustainable development challenges posed by other global pandemics and existential threats– including environmental pollution, climate change, economic inequities and social instability.

The R&D Equity initiative is co-created to become the multi-sectoral platform ready to tackle the challenge of improving global R&D ecosystems as essential for global health, equity and sustainable development.

- Global Preparedness – a multitude of actions but no comprehensive global plan for equitable prevention, preparedness and control.

Given the impact on health and well-being, on mental and social health, on the global economy, and even on political relations, the COVID-19 pandemic has given rise to a massive mobilisation of national and international efforts to deal with its consequences.

Broadly speaking, there are two kinds of efforts – those focused on ending the current pandemic (COVAX, temporary IP waivers, ACT-A, vaccine diplomacy, mental health interventions) and those focused (also) on preparedness for future pandemics. (The Independent Panel, CEPI, science collaborations, World Economic Forum group). All of these call for massive resource mobilisation for a single problem – pandemic control – without much reference to all the other priority R&D needs facing low- and middle-income countries.

The responses seem similar to control efforts following large epidemics in the recent past, such as Ebola Virus Disease outbreaks in West-Africa: once the epidemic has been brought under control, substantive action stops. If we are to achieve global preparedness and more equitable action in dealing with future global challenges, then much more needs to be done in inter-pandemic periods.

The effectiveness and sustainability of a more equitable global R&D preparedness ecosystem and R&D Equity needs long-term effort, global collaboration and willingness of countries and other actors to commit major financial resources. It needs leadership which must emanate from the countries themselves, not taken over by the traditional global or bi-lateral institutions leading past efforts.

Investments in R&D ecosystem development will only happen if these investments will also contribute to social and economic progress, job creation, reduction of inequities, and mitigation of climate change impact.

R&D Equity implies R&D ecosystem development as an essential link to global preparedness for many other risks to health, well-being, and socio-economic development. The Global R&D Preparedness Ecosystem needs to be inclusive, flexible, responsive, and should create an R&D ecosystem that can be repurposed rapidly, effectively and equitably to deal with new challenges, and at the same time serve as essential components for achieving the SDG 2030 agenda.

Although there are a multitude of national and multilateral initiatives, private sector efforts and non-profit calls to action, there is no shared global vision of global preparedness. R&D Equity aims to fill the gap that exists in the contribution of science and science implementation in the global vision of global preparedness.

- R&D Equity – the action agenda

… manufacturing capacity of mRNA and other vaccines must urgently be built in Africa, Latin America and other low- and middle-income regions. Vaccine manufacturing is highly specialized and difficult. Boosting production takes time so enabling it must begin now.

(The Independent Panel report, May 2021, p13)

Comprehensive action is required now to prepare for the future. At this time, there are many ideas, many organizations, many initiatives, many business plans but no obvious coordinator of a concerted, inclusive and global R&D Equity effort.

To achieve success in R&D Equity requires substantive support from many quarters, primarily, but certainly not exclusively, from governments, particularly in low- and middle-income countries themselves.

Effective partnerships with business, academia, science bodies, financiers and philanthropies, and non-profit organisations are essential for success. For this reason, we have to look beyond the usual inter-governmental bodies to realize the full potential of R&D Equity and achieve capable national and global R&D preparedness ecosystems.

Supporting the SDG 2030 Agenda

Building ‘Global R&D Preparedness Ecosystems’ is a long-term, inclusive, multi-sectoral, generic and resource-intensive effort. It is not one concerted effort but will consist of many different efforts and initiatives at many different levels. Such investments are not realistic, may not be ethical and are unlikely to be sustained if they do not also serve other national and global development goals and priorities at the same time. SDG 2030 compatibility is key to success of R&D Equity and global preparedness.

To guide action towards global R&D equity, COHRED proposes five core values:

- Actions have to be equity focused – within countries and between countries.

- Actions have to be deeply collaborative – between public, private and non-profit sectors, between nations, and between science and the general public.

- Actions have to include low- and middle-income countries as active and equal players, with explicit roles and responsibilities to contribute to local and global R&D preparedness.

- All actors have to consider and use the inter-pandemic and inter-global-challenge periods as essential preparation time for investment and support.

- Actions cannot be constructed as another ‘vertical programme’. Effective and equitable global preparedness requires many resources and impacts on so many aspects of societies that it cannot succeed if it is designed as (yet) another ‘vertical programme’. R&D Equity has to be seen as a key input into national and global growth and development, trade, exchange, and technology transfer – in brief – as a major contributor to achieving SDG 2030 Agenda.

R&D Equity Action Agenda

Based on these values, the global R&D Equity initiative should start with a 3-year intensive preparation, planning, mapping and co-creation phase to:

- Convene the Commission on R&D Equity for Global Preparedness

-Driven by LMICs with support from other parties interested in working towards equitable global preparedness

-Decide and agree on responsibilities and inclusive decision-making

-COHRED will act as host and incubator – leaving open the organizational options for the future

- Generate a Global R&D Equity Atlas

-Define scope and content of R&D ecosystems and R&D Equity

-Map R&D Equity globally – develop agreed indicators

-Provide country- and region-specific data on R&D ecosystem readiness

- Link R&D Equity to other Global Preparedness efforts and SDG 2030 goals

-Engage other relevant agencies and actors – public, private, non-profit; bilateral and multilateral; regional and global

-Arrange meetings, colloquia, fora, virtual networks

-Build consensus and synergy that supports the growth of R&D ecosystems in low- and middle-income countries, promote tools needed for fair and equitable R&D partnerships

- Prepare the R&D Equity Programme of Work for a more Equitable Future

-Present a comprehensive action plan for R&D Equity at the end of 3 years

-Agree on the organisational and financial measures, partners and collaborations to implement the Plan of Work

-Co-design, finance and implement the indicators and monitoring & evaluation, and the organizational infrastructure for regular reporting

- Financial and Other Engagements to support the Commission’s work

COHRED will invite countries that are already firmly committed to supporting R&D Equity – nationally, regionally or globally – and are willing to invest time, expertise, diplomatic, political, financial and other resources towards achieving R&D Equity in pursuit of global preparedness.

The founding group will have a membership of 4 countries, of which at least 2 are classified as low- and middle-income countries.

Ideally, commitments will be made in order to begin preparations for the Commission to begin its work by July 2022.

Expectations of Country Partnership and Contributions

- Participating countries will commit to support the Commission on R&D Equity for Global Preparedness as outlined in this document, in writing, to COHRED.

- This will include a financial commitment to enable the programme of work of the Commission during the first 3 years.

- The Commission’s work and operations require that founding countries contribute $1.5 Million for the three year period (i.e. $0.5 million per year).

- The Commission may decide to change the financial contributions for countries and other parties joining later.

- To facilitate low-income country participation, self-funding countries and non-state actors interested in supporting the Commission’s work may consider sponsoring the fees for a low-income country interested in participating in the Commission’s work.

- As part of their contributions, countries are encouraged to provide technical and non-financial resources needed to achieve the work of the initial three-year programme of work of the Commission – in addition to their financial contribution.

This may include institutional and technical support; it could include staff, offices, meeting support, advocacy and diplomatic efforts, and any other services that may enhance the prestige and impact of the Commission’s work.

- Be willing to start by July 2022 or as soon as possible thereafter.

- Countries interested in joining the COHRED Board of Directors are welcome to send such expression of interest to the Executive Director. COHRED is open to discuss any suggestions that can strengthen the Commission on R&D Equity for Global Preparedness.

- Working with COHRED

The Council on Health Research for Development (COHRED) was established in 1993 as an independent, international non-governmental organisation to support low- and middle-income countries to implement the ‘Essential National Health Research’ (ENHR) strategy. Over the years, COHRED has partnered with many countries that were and are committed to use science for health, equity and development – from the smallest countries, including Cuba, Benin, Vanuatu and Laos PDR, to the largest ones, including Nigeria, Brazil, The Philippines, Thailand and China.

COHRED has progressively widened its focus from the original ENHR strategy. At first, from the Second International Conference on Health Research for Development in Bangkok in 2000, this effort concentrated on supporting the definition and strengthening of ‘national health research systems’ (NHRS).

In subsequent years, COHRED’s initiated the message that ‘health research’ is too limited a concept to really achieve health and that ‘research for health’ should be the new way forward. By 2008, the WHO, COHRED and the Global Forum on Health Research had teamed up with Mali to deliver this message loud and clear during the Bamako Forum on Research for Health in 2008. Since then, COHRED has been engaging with research systems in many low- and middle-income countries, on request, to work on national research system development that could address health, equity and socio-economic development.

Most recently, COHRED developed the prime global tool to create transparency in and learning for fairness in global research partnerships involving low- and middle-income countries – the Research Fairness Initiative (RFI). The RFI is also intended as a very pragmatic instrument to operationalize SDG 17 (“Partnership for the SDGs”).

COHRED is not a funder; rather it receives funding from bilateral and multi-lateral agencies, philanthropies, regional organizations, and from selected businesses for specific projects. User fees for some of its services has supported its revenue generation. COHRED remains independent of sectoral, political or other interests. COHRED’s approach has always been one of ‘inclusiveness’ of all partners, consultation, co-design and co-creation, and – as a result – COHRED is seen by many in low- and middle-income countries as a trusted partner.

Structurally, COHRED is an Association under Swiss Law in the Canton of Geneva and is recognized as a ‘non-State Actor in official relations with the WHO’. It also holds observer status with WIPO, the World Intellectual Property Organization. It has an affiliate organization based in the State of Delaware in the USA (COHRED USA). The Global Forum for Health Research merged into COHRED in 2011 – providing substantive institutional capabilities and memory of hosting global meetings, large and small.

The Board and Management of COHRED believe that with its unique focus on research system capacity support for low- and middle-income countries since 1993, its engagement with many governments – research organizations and businesses – non-profit organizations – bilateral and philanthropic funders over more than 25 years, as well as its continued international and independent organizational and financing model, COHRED offers the best organizational basis to host and incubate the R&D Equity initiative and platform. This enables all future organizational options to remain open, including creating an organizational framework outside COHRED.

Council on Health Research for Development (COHRED)

1-5 route des Morillons 1211, Geneva 2, Switzerland

——-

Appendix

Key Reference Documents

A New Commitment for Vaccine Equity and Defeating the Pandemic. (“Investing US$ 50 billion to end the pandemic is potentially the best use of public money we will see in our lifetimes”). Kristalina Georgieva (IMF), Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus (WHO), David Malpass (World Bank Group), Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala (WTO). World Health Organization, Newsroom. 31 May 2021.

Advancing Epidemics R&D to keep up with a changing world: progress, challenges and opportunities. Wellcome Trust. 12 August 2019.

African countries must muscle up their support and fill massive R&D gap. Janet Midega, Catherine Kyobutungi, Emelda Okiro, Fredros Okumu, Ifeyinwa Aniebo, Ngozi Erondu. The Conversation. 18 May 2021.

Audit of the World Health Organization (WHO) for the Financial Year ended 31 December 2020. Office of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India. 17 May 2021.

China’s International Development Cooperation in the New Era. The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China. January 2021.

COVID-19: Collaboration is the engine of global science – especially for developing countries. Kituyi M. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/global-science-collaboration-open-source-covid-19/. 15 May 2020/

COVID-19: make it the last pandemic. The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response. May 2021.

COVID-19 preparedness: capacity to manufacture vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics in sub-Saharan Africa. Bisi B, Chinedum PB, Sam-Agudu NA, et al. BMC Globalization and Health. 2021.

Covid-19 Research And Innovation Achievements. WHO. R&D Blueprint. April 2021.

Definitions of Research and Development: An Annotated Compilation of Official Sources. National Science Foundation (USA). March 2018

DOST, DOH to probe vaccine mixed-dose approach. Philippine Council for Health Research and Development. https://www.pchrd.dost.gov.ph/news/6678-dost-doh-to-probe-vaccine-mixed-dose-approach. 31 May 2021.

Fair Research Contracting (FRC). https://frcweb.cohred.org

France and development research. https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/french-foreign-policy/scientific-diplomacy/france-and-development-research/. Accessed June 2021

France to help Africa boost Covid-19 vaccine production, Macron says. France 24. 28 May 2021. https://f24.my/7hn7

G7 must bear the burden of vaccinating the world. Time is short if the battle against Covid-19 is to be won and the economic gains realised. Gordon Brown. Opinion Covid-19 vaccines. Financial Times 22 May 2021.

Health Research. Essential link to equity in development. Commission on Health Research for Development. Oxford University Press, 1990. http://www.cohred.org/publications/open-archive/1990-commission-report/

New Partnership To Boost Africa’s Vaccine Research, Development And Manufacturing. Health Policy Watch. 15 April 2021.

Outbreak Readiness and Business Impact. Protecting Lives and Livelihoods across the Global Economy. World Economic Forum. 2019.

Overcoming gaps to advance global health equity: a symposium on new directions for research. Frenk J, Chen L. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2011.

Post-pandemic transformations: How and why COVID-19 requires us to rethink development. Leach M, MacGregor H, Scoones I, Wilkinson A. World Development. 16 October 2020.

Priorities for COVID-19 research response and preparedness in low-resource settings. GLOPiD-R Secretariat. Lancet 22 May 2021.

Prioritizing Financing Systems for Pandemic Preparedness? Carel IJsselmuiden, Francine Ntoumi, James V Lavery, Jaime Montoya, Salim Abdool Karim, Kirsty Kaiser. Lancet 2021, July 31; 398: 388.

Research Fairness Initiative (RFI). https://rfi.cohred.org

Restoring Vaccine Diplomacy. Hotez PJ, Narayan KMV. J American Medical Assocation (published online). 28 May 2021

South Africa and the Global South’s battle for Covid-19 vaccine justice. ‘The loss of humanity’. Karrim A. https://www.news24.com/news24/opinions/fridaybriefing/the-big-picture-the-loss-of-humanity-south-africa-and-the-global-souths-battle-for-covid-19-vaccine-justice-20210304 News24. 4 March 2021.

Swiss Health Foreign Policy 2019-2024. Swiss Federal Council. 15 May 2019.

The Collapse of Global Cooperation under the WHO International Health Regulations at the Outset of COVID-19: Sculpting the Future of Global Health Governance. Taylor AL, Habibi R. ASIL Insights. The American Society of International Law. 5 June 2020.

The COVID vaccine pioneer behind southeast Asia’s first mRNA shot. Nature. 26 May 2021.

The Neglected Dimension of Global Security: A Framework to Counter Infectious Disease Crises. Commission on a Global Health Risk Framework for the Future. National Academy of Sciences (USA). 2016.

The R&D Preparedness Ecosystem: Preparedness for Health Emergencies Report to the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board. Keusch GT, Lurie N. US National Academy of Medicine. 9 August 2020.

UN chief calls for a global partnership to address COVID, climate change and achieve SDG’s. UN News. 30 May 2021. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/05/1093052)

Urgent lessons from COVID 19: why the world needs a standing, coordinated system and sustainable financing for global research and development. Lurie N, Keusch GT, Dzau VJ. Lancet. 9 March 2021.

Wanted: trusted rules for emergency data access. Editorial. Nature 3 June 2021; Vol 594, 8.

Abbreviations & terms

ACT-A Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator

CEPI Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations

COHRED Council on Health Research for Development

COVAX Facility COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access Facility

COVID-19 Corona Virus Disease

FRC Fair Research Contracting

GLOPID-R Global Research Collaboration for Infectious Disease Preparedness

IMF International Monetary Fund

IPR Intellectual Property Right(s)

R&D Research & Development, Research and Development

RFI Research Fairness Initiative

SDG 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (2030 Agenda)

WHA World Health Assembly

WHO World Health Organization

WIPO World Intellectual Property Organization

WTO World Trade Organization

—-

By COHRED recently on PEAH Fair Research Contracting – Key to Promoting Solidarity for Science and Development in a post-COVID-19 World by Carel IJsselmuiden, Kirsty Kaiser, Abigail Wilkinson, Farirai Mutenherwa Fair Research Partnerships in European Commission Funded Research by Carel IJsselmuiden and Kirsty Klipp